(Press-News.org) CHICAGO -- Northwestern Medicine researchers have discovered a "two-faced" group of cells at work in human colon cancer, with opposing functions that can suppress or promote tumor growth. These cells are a subset of T-regulatory (Treg) cells, known to suppress immune responses in healthy individuals

In this previously unknown Treg subset, the presence of the protein RORγt has been shown to differentiate between cancer-protecting and cancer-promoting properties.

The Northwestern team, led by Khashayarsha Khazaie, research associate professor at the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University, recently reported their findings in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

"The subset of Tregs that expand in human colon cancer is different from the Tregs that abound in healthy individuals in their ability to suppress inflammation," said Khazaie. "Since their discovery, Tregs have been assumed to be harmful in cancer based on the knowledge that they suppress immunity. More recent clinical studies have challenged this notion. Our work shows that Tregs, by suppressing inflammation, are normally very protective in cancer; it is rather their switch to the expression of RORγt that is detrimental."

The Northwestern team's work builds on observations, which demonstrated that the transfer of Tregs from healthy mice to mice with colitis or colitis-induced cancer actually protected the mice from colitis and colitis-induced cancer.

After identifying the abnormal Treg subset in mice with hereditary colon cancer, Khazaie and lead author Nichole Blatner, research assistant professor at Lurie Cancer Center, worked with Mary Mulcahy, MD, associate professor of hematology and oncology, radiology, and organ transplantation, and David Bentrem, MD, Harold L. and Margaret N. Method Research Professor in Surgery, of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, to look for the same cells in colon cancer patients.

"To our delight, we found the same Treg alterations in cancer patients," said Khazaie.

Of cancers affecting both men and women, colorectal cancer (cancer of the colon and rectum) is the second leading cancer killer in the United States. In 2012, approximately 140,000 Americans were diagnosed with colon or rectal cancer, while more than 50,000 deaths occurred from either cancer, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

"The significance of our discovery became apparent when by inhibiting RORgt in Tregs we were able to protect mice against hereditary colon cancer," Khazaie said.

He notes that several ongoing clinical trials exist based on targeted elimination of all Tregs in cancer patients. However, the discovery of Treg diversity in cancer, and its central role in control of cancer inflammation, may lead to new approaches for therapeutics.

"Tregs are actually very useful in the fight against cancer," he says. "We can do better by targeting RORγt or other molecules that are responsible for the expansion of this Treg subset, instead of indiscriminately eliminating all Tregs. We are very excited about the therapeutic options that targeting specific subsets of Tregs could provide in human solid tumor cancers, and that is our next immediate goal."

Khazaie's team is moving forward with plans to test novel drugs that inhibit RORγt.

INFORMATION:

This research was made possible by philanthropic support through the Lurie Cancer Center and Steven Rosen, MD, director of the Lurie Cancer Center and the Genevieve E. Teuton Professor of Medicine at the Feinberg School.

In addition to Northwestern University researchers, Khazaie and Blatner collaborated with Fotini Gounari, University of Chicago, and Christophe Benoist, Harvard Medical School, on this discovery.

END

ARGONNE, Ill. – For the first time, scientists witnessed the details of the full, ultrafast process of liquid droplets evolving into a bubble when they strike a surface. Their research determined that surface wetness affects the bubble's fate.

This research could one day help eliminate bubbles formed during spray coating, metal casting and ink-jet printing. It also could impact studies on fuel efficiency and engine life by understanding the splashing caused by fuel hitting engine walls.

"How liquid coalesces into a drop or breaks up into a splash when hitting something ...

Prostate cancer patients receiving the costly treatment known as proton radiotherapy experienced minimal relief from side effects such as incontinence and erectile dysfunction, compared to patients undergoing a standard radiation treatment called intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), Yale School of Medicine researchers report in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Standard treatments for men with prostate cancer, such as radical prostatectomy and IMRT, are known for causing adverse side effects such as incontinence and erectile dysfunction. Proponents of ...

New research by a University of Alberta archeologist may lead to a rethinking of how, when and from where our ancestors left Africa.

U of A researcher and anthropology chair Pamela Willoughby's explorations in the Iringa region of southern Tanzania yielded fossils and other evidence that records the beginnings of our own species, Homo sapiens. Her research, recently published in the journal Quaternary International, may be key to answering questions about early human occupation and the migration out of Africa about 60,000 to 50,000 years ago, which led to modern humans ...

Peach growers in California may soon have better tools for saving water because of work by U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) scientists in Parlier, Calif.

Agricultural Research Service (ARS) scientist Dong Wang is evaluating whether infrared sensors and thermal technology can help peach growers decide precisely when to irrigate in California's San Joaquin Valley. ARS is USDA's principal intramural scientific research agency, and the research supports the USDA priority of promoting international food security.

Irrigation is the primary source of water for agriculture ...

The plague-causing bacteria Yersinia pestis evades detection and establishes a stronghold without setting off the body's early alarms.

New discoveries reported this week help explain how the stealthy agent of Black Death avoids tripping a self-destruct mechanism inside germ-destroying cells.

The authors of the study, appearing in the Dec. 13 issue of Cell Host & Microbe, are Dr. Christopher N. LaRock of the University of Washington Department of Microbiology and Dr. Brad Cookson, UW professor of microbiology and laboratory medicine.

Normally, certain defender cells ...

A venomous primate with two tongues would seem safe from the pet trade, but the big-eyed, teddy-bear face of the slow loris (Nycticebus sp.) has made them a target for illegal pet poachers throughout the animal's range in southeastern Asia and nearby islands. A University of Missouri doctoral student and her colleagues recently identified three new species of slow loris. The primates had originally been grouped with another species. Dividing the species into four distinct classes means the risk of extinction is greater than previously believed for the animals but could ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — On the road to smaller, high-performance electronics, University of Illinois researchers have smoothed one speed bump by shrinking a key, yet notoriously large element of integrated circuits.

Three-dimensional rolled-up inductors have a footprint more than 100 times smaller without sacrificing performance. The researchers published their new design paradigm in the journal Nano Letters.

"It's a new concept for old technology," said team leader Xiuling Li, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Illinois.

Inductors, ...

Black holes range from modest objects formed when individual stars end their lives to behemoths billions of times more massive that rule the centers of galaxies. A new study using data from NASA's Swift satellite and Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope shows that high-speed jets launched from active black holes possess fundamental similarities regardless of mass, age or environment. The result provides a tantalizing hint that common physical processes are at work.

"What we're seeing is that once any black hole produces a jet, the same fixed fraction of energy generates the ...

VIDEO:

NASA's TRMM satellite passed above an intensifying Tropical Cyclone Evan on Dec. 11 at 1759 UTC (12:59 p.m. EST/U.S.) and saw the tallest thunderstorms around Evan's center of circulation reached...

Click here for more information.

NASA satellites have been monitoring Tropical Cyclone Evan and providing data to forecasters who expected the storm to intensify. On Dec. 13, Evan had grown from a tropical storm into a cyclone as NASA satellites observed cloud formation, ...

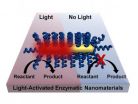

HOUSTON – (Dec. 13, 2012) – Since Edison's first bulb, heat has been a mostly undesirable byproduct of light. Now researchers at Rice University are turning light into heat at the point of need, on the nanoscale, to trigger biochemical reactions remotely on demand.

The method created by the Rice labs of Michael Wong, Ramon Gonzalez and Naomi Halas and reported today in the American Chemical Society journal ACS Nano makes use of materials derived from unique microbes – thermophiles – that thrive at high temperatures but shut down at room temperature.

The Rice project ...