(Press-News.org) Maintaining the right sodium levels in the body is crucial for controlling blood pressure and ensuring proper muscle function. Conventional wisdom has suggested that constant sodium levels are achieved through the balance of sodium intake and urinary excretion, but a new study in humans published by Cell Press on January 9th in the journal Cell Metabolism reveals that sodium levels actually fluctuate rhythmically over the course of weeks, independent of salt intake. This one-of-a-kind study, which examined cosmonauts participating in space-flight simulation studies, challenges widely accepted assumptions that sodium levels are maintained within very narrow limits.

"The study highlights the importance of measuring salt excretion in urine over a longer time period to accurately estimate salt intake," says senior study author Jens Titze of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. "This information is very important, given the emphasis on salt intake in terms of risk for cardiovascular disease and healthcare outcomes."

Past studies in humans have shown that when dietary salt intake increases, a steady state of sodium levels in the body is achieved through rapid urinary excretion. This process is under the control of a hormone called aldosterone, which causes sodium to be retained in the kidneys. However, most of these studies were short-term and did not examine fluctuations in sodium levels in response to constant salt intake.

To address these limitations, Titze and his team took advantage of a unique opportunity to control salt intake and study salt balance over the course of nearly seven months in 12 male participants in the Mars105 and Mars520 studies. These men spent 105 and 520 days, respectively, in an enclosed habitat consisting of hermetically sealed interconnecting modules at a spaceship simulation facility in Moscow, where they lived and worked as if they were cosmonauts at the international space station. As expected, their aldosterone levels increased when they consumed less salt. But surprisingly, a decrease in salt intake led to a reduction in levels of the "stress hormone" cortisol.

When the researchers kept salt intake constant, sodium excretion and the levels of aldosterone and cortisol fluctuated together in weekly cycles. On the other hand, sodium levels in the body exhibited longer-term rhythmic changes that were independent of salt intake. Over this longer timescale, elevated sodium levels were associated with high aldosterone levels and low cortisol levels, suggesting that the two hormones work in opposite ways to control sodium storage and release.

"To the best of our knowledge, the long-term rhythm we observed in sodium levels in the body has not been previously reported, and it was not known that cortisol and aldosterone work in opposite directions to regulate sodium metabolism," Titze says.

INFORMATION:

Rakova et al.: "Long-term space-flight simulation reveals infradian rhythmicity in human Na+ balance."

Space-simulation study reveals sodium rhythms in the body

2013-01-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Most physicians do not meet Medicare quality reporting requirements

2013-01-08

Washington, DC – A new Harvey L. Neiman Health Policy Institute study shows that fewer than one-in-five healthcare providers meet Medicare Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) requirements. Those that meet PQRS thresholds now receive a .5 percent Medicare bonus payment. In 2015, bonuses will be replaced by penalties for providers who do not meet PQRS requirements. As it stands, more than 80 percent of providers nationwide would face these penalties.

Researchers analyzed 2007-2010 PQRS program data and found that nearly 24 percent of eligible radiologists qualified ...

Genes and obesity: Fast food isn't only culprit in expanding waistlines -- DNA is also to blame

2013-01-08

Researchers at UCLA say it's not just what you eat that makes those pants tighter — it's also genetics. In a new study, scientists discovered that body-fat responses to a typical fast-food diet are determined in large part by genetic factors, and they have identified several genes they say may control those responses.

The study is the first of its kind to detail metabolic responses to a high-fat, high-sugar diet in a large and diverse mouse population under defined environmental conditions, modeling closely what is likely to occur in human populations. The researchers ...

Brief class on easy-to-miss precancerous polyps ups detection, Mayo study shows

2013-01-08

JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — Most people know a colonoscopy requires some preparation by the patient. Now, a Mayo Clinic physician suggests an additional step to lower the risk of colorectal cancer: Ask for your doctor's success rate detecting easy-to-miss polyps called adenomas.

The measure of success is called the adenoma detection rate, or ADR, and has been linked to a reduced risk of developing a new cancer after the colonoscopy. The current recommended national benchmark is at least 20 percent, which means that an endoscopist should be able to detect adenomas in at least ...

New research may explain why obese people have higher rates of asthma

2013-01-08

New York, NY — A new study led by Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) researchers has found that leptin, a hormone that plays a key role in energy metabolism, fertility, and bone mass, also regulates airway diameter. The findings could explain why obese people are prone to asthma and suggest that body weight–associated asthma may be relieved with medications that inhibit signaling through the parasympathetic nervous system, which mediates leptin function. The study, conducted in mice, was published in the online edition of the journal Cell Metabolism.

"Our study ...

Simulated Mars mission reveals body's sodium rhythms

2013-01-08

Clinical pharmacologist Jens Titze, M.D., knew he had a one-of-a-kind scientific opportunity: the Russians were going to simulate a flight to Mars, and he was invited to study the participating cosmonauts.

Titze, now an associate professor of Medicine at Vanderbilt University, wanted to explore long-term sodium balance in humans. He didn't believe the textbook view – that the salt we eat is rapidly excreted in urine to maintain relatively constant body sodium levels. The "Mars500" simulation gave him the chance to keep salt intake constant and monitor urine sodium levels ...

Researchers identify new target for common heart condition

2013-01-08

Researchers have found new evidence that metabolic stress can increase the onset of atrial arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation (AF), a common heart condition that causes an irregular and often abnormally fast heart rate. The findings may pave the way for the development of new therapies for the condition which can be expected to affect almost one in four of the UK population at some point in their lifetime.

The British Heart Foundation (BHF) study, led by University of Bristol scientists and published in Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology, found that metabolic ...

DNA prefers to dive head first into nanopores

2013-01-08

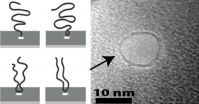

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — If you want to understand a novel, it helps to start from the beginning rather than trying to pick up the plot from somewhere in the middle. The same goes for analyzing a strand of DNA. The best way to make sense of it is to look at it head to tail.

Luckily, according to a new study by physicists at Brown University, DNA molecules have a convenient tendency to cooperate.

The research, published in the journal Physical Review Letters, looks at the dynamics of how DNA molecules are captured by solid-state nanopores, tiny holes that ...

Scientists mimic fireflies to make brighter LEDs

2013-01-08

The nighttime twinkling of fireflies has inspired scientists to modify a light-emitting diode (LED) so it is more than one and a half times as efficient as the original. Researchers from Belgium, France, and Canada studied the internal structure of firefly lanterns, the organs on the bioluminescent insects' abdomens that flash to attract mates. The scientists identified an unexpected pattern of jagged scales that enhanced the lanterns' glow, and applied that knowledge to LED design to create an LED overlayer that mimicked the natural structure. The overlayer, which increased ...

Unlike we thought for 100 years: Molds are able to reproduce sexually

2013-01-08

For over 100 years, it was assumed that the penicillin-producing mould fungus Penicillium chrysogenum only reproduced asexually through spores. An international research team led by Prof. Dr. Ulrich Kück and Julia Böhm from the Chair of General and Molecular Botany at the Ruhr-Universität has now shown for the first time that the fungus also has a sexual cycle, i.e. two "genders". Through sexual reproduction of P. chrysogenum, the researchers generated fungal strains with new biotechnologically relevant properties - such as high penicillin production without the contaminating ...

Parasitic worms may help treat diseases associated with obesity

2013-01-08

Athens, Ga. – On the list of undesirable medical conditions, a parasitic worm infection surely ranks fairly high. Although modern pharmaceuticals have made them less of a threat in some areas, these organisms are still a major cause of disease and disability throughout much of the developing world.

But parasites are not all bad, according to new research by a team of scientists now at the University of Georgia, the Harvard School of Public Health, the Université François Rabelais in Tours, France, and the Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China.

A study ...