(Press-News.org) A University of Arizona-led team of astronomers for the first time has used NASA's Spitzer and Hubble space telescopes simultaneously to peer into the stormy atmosphere of a brown dwarf, creating the most detailed "weather map" yet for this class of strange, not-quite-star-and-not-quite-planet objects. The forecast shows wind-driven, planet-sized clouds enshrouding these strange worlds.

Brown dwarfs form out of condensing gas like stars but fail to accrue enough mass to ignite the nuclear fusion process necessary to turn them into a star. Instead, they pass their lives as dimly glowing, constantly cooling gas balls similar to gas planets with their complex, varied atmospheres. The new research is a stepping stone toward better understanding not only brown dwarfs but also the atmospheres of planets beyond our solar system.

"With Hubble and Spitzer, we were able to look at the layers of a brown dwarf, similar to the way doctors use medical imaging techniques to study the different tissues in your body," said Daniel Apai, the principal investigator of the research from the UA, who presented the results at the American Astronomical Society meeting in Long Beach, Calif. Apai is an assistant professor with joint appointments in the UA's departments of astronomy and planetary sciences.

A study describing the results, led by Esther Buenzli, a postdoctoral researcher in the UA's department of astronomy, is published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The researchers turned Hubble and Spitzer simultaneously toward a brown dwarf called 2MASSJ22282889-431026. They found that its light varied in time, brightening and dimming as the body rotated around every 1.4 hours. But more surprising, the team also found that the timing of this brightening changed depending on whether they looked at it with Spitzer or Hubble using different wavelengths of infrared light (Hubble sees shorter-wavelength infrared light than Spitzer).

These variations are the result of different layers, or patches, of material swirling around the brown dwarf in windy storms as large as Earth itself. Spitzer and Hubble see different atmosphere layers because certain infrared wavelengths are blocked by vapors of water and methane high up, while other infrared wavelengths emerge from much deeper.

"What we see here is evidence for massive, organized cloud systems, perhaps akin to giant versions of the Great Red Spot on Jupiter or large-scale storm systems on Earth," said Adam Showman, a theorist with the UA's Lunar and Planetary Laboratory who was involved in the research.

"We were expecting the phases of the light variations to be in sync between the two telescopes, so we were really surprised that they were offset," said Buenzli. "This is the first time that we can probe variability at several different altitudes at the same time in the atmosphere of a brown dwarf."

"The deeper layers appear to lag behind the higher layers," Apai explained. "This tells us that the same or similar cloud distribution is present in the different layers, but the deeper you look, the later you will see the same clouds turning into view."

"We were very surprised to see such a big lag. Our best guess is this has to do with the brown dwarf's atmospheric circulation. The bigger picture here is that we see a very large-scale atmospheric structure in this brown dwarf."

"These out-of-sync light variations provide a fingerprint of how the brown dwarf's weather systems stack up vertically," added Showman. "The data suggest that regions on the brown dwarf where the weather is moist and cloudy deep in the atmosphere coincide with balmier, drier conditions at higher altitudes – and vice versa."

Ranging in size between Jupiter and the smallest stars and commonly weighing in at 30-40 Jupiter masses, brown dwarfs are cool relative to other stars but quite hot by our Earthly standards. This particular object is about 600 to 700 degrees Celsius (1,100 to 1,300 degrees Fahrenheit). Being quite warm, they emit strongly in the infrared, wavelengths picked up by Spitzer and Hubble.

At the cooler, outer layers of the star, gas condenses into smoke-sized particles, including sand and iron, which fall down into the interior as a sandy and iron rain. Just like on Earth, the iron and sand "raindrops" heat up as they enter the deeper warmer layer and eventually evaporate, triggering a rain cycle.

Apai said the atmospheric dynamics on brown dwarfs are very different from those here on Earth.

"On our planet, we have only one species of cloud - water," he explained, "But on this brown dwarf, there is such a wide temperature range that we have many different species of clouds."

In three ongoing Spitzer programs, Apai and his co-investigators have successfully explored the properties of cloud covers in about 50 brown dwarfs.

"As different wavelengths probe different pressures and different rotational phases probe different latitudes we will be able to explore the two or even three-dimensional structure of the atmospheres," Apai said.

Buenzli said that theorists are excited to model the new data: a new era of weather reporting has begun.

"Eventually, we want to probe the atmospheres of exoplanets in a similar fashion," she said.

"Currently, we can't get this type of data on exoplanets because their bright host stars blind our vision," Apai said. "Brown dwarfs are the perfect laboratories for studying the exotic science of worlds beyond our own."

The findings are the first published from a set of Spitzer and Hubble space telescope programs led by Apai. By mapping cloud systems in brown dwarfs, these studies are opening a new field, extrasolar atmospheric dynamics, which bridges astronomy and planetary science.

Apai is the principal investigator of the project Extrasolar Storms, which uses the Spitzer and Hubble space telescope together to follow the evolution of gigantic storms in the atmospheres of brown dwarfs over 1.5 years. Storms is one of the largest projects ever approved for the Spitzer Space Telescope, equaling two months of continuous observations with this $1 billion telescope. Launched in 2003, Spitzer has long exceeded its nominal lifetime. A group led by UA Regents' Professor George Rieke developed one of Spitzer's infrared detectors, the Multiband Imaging Photometer.

The Storms team includes 12 experts from the U.S., Canada and the UK, four of which are at the UA: In addition to Apai, Buenzli and Showman, Davin Flateau, another graduate student of Apai's is part of the team.

"Brown dwarfs are fascinating and diverse," said Apai. "Now we've got a new technique to chase their gigantic and violent storms."

### END

Scientists peer into a brown dwarf, find stormy atmosphere

2013-01-09

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Asteroid belt found around Vega

2013-01-09

Vega, the second brightest star in northern night skies, has an asteroid belt much like our sun, discovered by a University of Arizona-lead team of astronomers. A wide gap between the dust belts in nearby bright stars is a strong hint of yet-undiscovered planets orbiting the stars.

The findings from the Infrared Space Telescopes are the first to show an asteroid-like belt ringing Vega. The discovery of an asteroid belt around Vega makes it more similar to its twin, a star called Fomalhaut, than previously known. Both stars now are known to have inner, warm asteroid belts ...

JCI early table of contents for Jan. 9, 2013

2013-01-09

Small peptide ameliorates autoimmune skin blistering disease in mice

Pemphigus vulgaris is a life-threatening autoimmune skin disease that is occurs when the body's immune system generates antibodies that target proteins in the skin known as desomogleins. Desmogleins help to form the adhesive bonds that hold skin cells together and keep the skin intact. Currently, pemphigus vulgaris is treated by long-term immune suppression; however, this can leave the patient susceptible to infection. In this issue of the Journal of Clinical Investigation, researchers led by Jens Waschke ...

Small peptide ameliorates autoimmune skin blistering disease in mice

2013-01-09

Pemphigus vulgaris is a life-threatening autoimmune skin disease that is occurs when the body's immune system generates antibodies that target proteins in the skin known as desomogleins. Desmogleins help to form the adhesive bonds that hold skin cells together and keep the skin intact. Currently, pemphigus vulgaris is treated by long-term immune suppression; however, this can leave the patient susceptible to infection. In this issue of the Journal of Clinical Investigation, researchers led by Jens Waschke at the Institute of Anatomy and Cell Biology in Munich, Germany, ...

Newly found 'volume control' in the brain promotes learning, memory

2013-01-09

WASHINGTON — Scientists have long wondered how nerve cell activity in the brain's hippocampus, the epicenter for learning and memory, is controlled — too much synaptic communication between neurons can trigger a seizure, and too little impairs information processing, promoting neurodegeneration. Researchers at Georgetown University Medical Center say they now have an answer. In the January 10 issue of Neuron, they report that synapses that link two different groups of nerve cells in the hippocampus serve as a kind of "volume control," keeping neuronal activity throughout ...

A new treatment for kidney disease-associated heart failure?

2013-01-09

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients frequently suffer from mineral bone disorder, which causes vascular calcification and, eventually, chronic heart failure. Similar to patients with CKD, mice with low levels of the protein klotho (klotho hypomorphic mice) also develop vascular calcification and have shorter life spans compared to normal mice. In this issue of the Journal of Clinical Investigation, Florian Lang and colleagues at the University of Tübingen in Germany, found that treatment with the mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist spironolactone reduced vascular calcification ...

Fusion gene contributes to glioblastoma progression

2013-01-09

Fusion genes are common chromosomal aberrations in many cancers, and can be used as prognostic markers and drug targets in clinical practice. In this issue of the Journal of Clinical Investigation, researchers led by Matti Annala at Tampere University of Technology in Finland identified a fusion between the FGFR3 and TACC3 genes in human glioblastoma samples. The protein produced by this fusion gene promoted tumor growth and progression in a mouse model of glioblastoma, while increased expression of either of the normal genes did not alter tumor progression. Ivan Babic ...

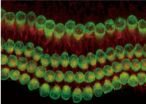

Regeneration of sound sensing cells recovers hearing in mice with noise-induced deafness

2013-01-09

Extremely loud noise can cause irreversible hearing loss by damaging sound sensing cells in the inner ear that are not replaced. But researchers reporting in the January 9 issue of the Cell Press journal Neuron have successfully regenerated these cells in mice with noise-induced deafness, partially reversing their hearing loss. The investigators hope the technique may lead to development of treatments to help individuals who suffer from acute hearing loss.

While birds and fish are capable of regenerating sound sensing hair cells in the inner ear, mammals are not. Scientists ...

Mathematics and weather and climate research

2013-01-09

San Diego, California – January 9, 2013 – How does mathematics improve our understanding of weather and climate? Can mathematicians determine whether an extreme meteorological event is an anomaly or part of a general trend? Presentations touching on these questions will be given at the annual national mathematics conference in San Diego, California. New results will also be presented on the MJO (pronounced "mojo"), a tropical atmospheric wave which governs monsoons and also impacts rainfall in North America, and yet does not fit into any current computer models of the ...

BPA linked to potential adverse effects on heart and kidneys

2013-01-09

NEW YORK (January 9, 2013) – Exposure to a chemical once used widely in plastic bottles and still found in aluminum cans appears to be associated with a biomarker for higher risk of heart and kidney disease in children and adolescents, according to an analysis of national survey data by NYU School of Medicine researchers published in the January 9, 2013, online issue of Kidney International, a Nature publication.

Laboratory studies suggest that even low levels of bisphenol A (BPA) like the ones identified in this national survey of children and adolescents increase oxidative ...

E-games boost physical activity in children; might be a weapon in the battle against obesity

2013-01-09

WASHINGTON—Video games have been blamed for contributing to the epidemic of childhood obesity in the United States. But a new study by researchers at the George Washington University School of Public Health and Health Services (SPHHS) suggests that certain blood-pumping video games can actually boost energy expenditures among inner city children, a group that is at high risk for unhealthy weight gain.

The study, "Can E-gaming be Useful for Achieving Recommended Levels of Moderate to Vigorous-Intensity Physical Activity in Inner-City Children," will appear January 9 in ...