(Press-News.org) The Earth's forests perform a well-known service to the planet, absorbing a great deal of the carbon dioxide pollution emitted into the atmosphere from human activities. But when trees are killed by natural disturbances, such as fire, drought or wind, their decay also releases carbon back into the atmosphere, making it critical to quantify tree mortality in order to understand the role of forests in the global climate system. Tropical old-growth forests may play a large role in this absorption service, yet tree mortality patterns for these forests are not well understood.

Now scientist Jeffrey Chambers and colleagues at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) have devised an analytical method that combines satellite images, simulation modeling and painstaking fieldwork to help researchers detect forest mortality patterns and trends. This new tool will enhance understanding of the role of forests in carbon sequestration and the impact of climate change on such disturbances.

"One quarter of CO2 emissions are going to terrestrial ecosystems, but the details of those processes and how they will respond to a changing climate are inadequately understood, particularly for tropical forests," Chambers said. "It's important we get a better understanding of the terrestrial sink because if it weakens, more of our emissions will end up in the atmosphere, increasing the rate of climate warming. To develop a better estimate of the contribution of forests, we need to have a better understanding of forest tree mortality."

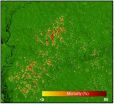

Chambers, in close collaboration with Robinson Negron-Juarez at Tulane University, Brazil's National Institute for Amazon Research (Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia [INPA]) and other colleagues, studied a section of the Central Amazon spanning over a thousand square miles near Manaus, Brazil. By linking data from Landsat satellite images over a 20-year period with observations on the ground, they found that 9.1 to 16.9 percent of tree mortality was missing from more conventional plot-based analyses of forests. That equates to more than half a million dead trees each year that had previously been unaccounted for in studies of this region, and which need to be included in forest carbon budgets.

Their findings were published online this week in a paper titled, "The steady-state mosaic of disturbance and succession across an old-growth Central Amazon forest landscape," in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

"If these results hold for most tropical forests, then it would indicate that because we missed some of the mortality, then the contribution of these forests to the net sink might be less than previous studies have suggested," Chambers said. "An old-growth forest has a mosaic of patches all doing different things. So if you want to understand the average behavior of that system you need to sample at a much larger spatial scale over larger time intervals than was previously appreciated. You don't see this mosaic if you walk through the forest or study only one patch. You really need to look at the forest at the landscape scale."

Trees and other living organisms are key players in the global carbon cycle, a complex biogeochemical process in which carbon is exchanged among the atmosphere, the ocean, the biosphere and Earth's crust. Fewer trees mean not only a weakening of the forest's ability to absorb carbon, but the decay of dead trees will also release carbon dioxide back into the atmosphere. Large-scale tree mortality in tropical ecosystems could thus act as a positive feedback mechanism, accelerating the global warming effect.

The Amazon forest is hit periodically by fierce thunderstorms that may bring violent winds with concentrated bursts believed to be as high as 170 miles per hour. The storms can blow down many acres of the forest; however, Chambers and his team were able to paint a much more nuanced picture of how storms affected the forest.

By looking at satellite images before and after a storm, the scientists discerned changes in the reflectivity of the forest, which they assumed was due to damage to the canopy and thus tree loss. Researchers were then sent into the field at some of the blowdown areas to count the number of trees felled by the storm. Looking at the satellite images pixel by pixel (with each pixel representing 900 square meters, or about one-tenth of a football field) and matching them with on-the-ground observations, they were able to draw a detailed mortality map for the entire landscape, which had never been done before.

Essentially they found that tree mortality is clustered in both time and space. "It's not blowdown or no blowdown—it's a gradient, with everything in between," he said. "Some areas have 80 percent of trees down, some have 15 percent."

In one particularly violent storm in 2005, a squall line more than 1,000 miles long and 150 miles wide crossed the entire Amazon basin. The researchers estimated that hundreds of millions trees were potentially destroyed, equivalent to a significant fraction of the estimated mean annual carbon accumulation for the Amazon forest. This finding was published in 2010 in Geophysical Research Letters. Intense 100-year droughts also caused widespread tree mortality in the Amazon basin in 2005 and 2010.

As climatic warming is expected to bring more intense droughts and stronger storms, understanding their effect on tropical and forest ecosystems becomes ever more important. "We need to establish a baseline so we can say how these forests functioned before we changed the climate," Chambers said.

This new tool can be used to assess tree mortality in other types of forests as well. Chambers and colleagues reported in the journal Science in 2007 that Hurricane Katrina killed or severely damaged about 320 million trees. The carbon in those trees, which would eventually be released into the atmosphere as CO2 as the trees decompose, was about equal to the net amount of carbon absorbed by all U.S. forests in a year.

Disturbances such as Superstorm Sandy and Hurricane Katrina cause large impacts to the terrestrial carbon cycle, forest tree mortality and CO2 emissions from decomposition, in addition to significant economic impacts. However, these processes are currently not well represented in global climate models. "A better understanding of tree mortality provides a path forward towards improving coupled earth system models," Chambers said.

Besides understanding how forests affect carbon cycling, the new technique could also play a vital role in understanding how climate change will affect forests. Although the atmospheric CO2 concentration has been rising for decades, we are now only just starting to feel the effects of a warming climate, such as melting glaciers, stronger heat waves and more violent storms.

"But these climate change signals will start popping out of the noise faster and faster as the years go on," Chambers said. "So, what's going to happen to old-growth tropical forests? On one hand they are being fertilized by some unknown extent by the rising CO2 concentration, and on the other hand a warming climate will likely accelerate tree mortality. So which of these processes will win out in the long-term: growth or death? Our study provides the tools to continue to make these critical observations and answer this question as climate change processes fully kicks in over the coming years."

INFORMATION:

Chambers' co-authors on the PNAS paper were Alan Di Vittorio of Berkeley Lab and Robinson Negron-Juarez, Daniel Marra, Joerg Tews, Dar Roberts, Gabriel Ribeiro, Susan Trumbore and Niro Higuchi of other institutions, including INPA, Brazil; Tulane University, USA; Noreca Consulting Inc, Canada; the University of California at Santa Barbara, USA; and the Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry, Germany.

This study was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world's most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab's scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science. For more, visit www.lbl.gov.

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

New research will help shed light on role of Amazon forests in global carbon cycle

Berkeley Lab scientists devise new tools for detecting previously unknown tree mortality

2013-01-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

The tales teeth tell

2013-01-29

For more than two decades, scientists have relied on studies that linked juvenile primate tooth development with their weaning as a rough proxy for understanding similar developmental landmarks in the evolution of early humans. New research from Harvard, however, is challenging those conclusions by showing that tooth development and weaning aren't as closely related as previously thought.

Using a first-of-its-kind method, a team of researchers led by professors Tanya Smith and Richard Wrangham and Postdoctoral Fellow Zarin Machanda of Harvard's Department of Human Evolutionary ...

Glial cells assist in the repair of injured nerves

2013-01-29

This press release is available in German.

Unlike the brain and spinal cord, the peripheral nervous system has an astonishing capacity for regeneration following injury. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute of Experimental Medicine in Göttingen have discovered that, following nerve damage, peripheral glial cells produce the growth factor neuregulin1, which makes an important contribution to the regeneration of damaged nerves.

From their cell bodies to their terminals in muscle or skin, neuronal extensions or axons in the peripheral nervous system are surrounded ...

EARTH: Drinking toilet water

2013-01-29

Alexandria, VA – Would you drink water from a toilet? What if that water, once treated, was cleaner than what comes out of the faucet? Although the imagery isn't appealing, as climate change and population growth strain freshwater resources, such strategies are becoming more common around the world — and in the United States.

Over the last several decades, local and regional water shortages have become increasingly common. These shortages have led to increased friction over water resources. Technologies are currently being developed to help make wastewater recycling ...

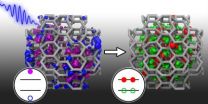

1 in, 2 out: Simulating more efficient solar cells

2013-01-29

Using an exotic form of silicon could substantially improve the efficiency of solar cells, according to computer simulations by researchers at the University of California, Davis, and in Hungary. The work was published Jan. 25 in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Solar cells are based on the photoelectric effect: a photon, or particle of light, hits a silicon crystal and generates a negatively charged electron and a positively charged hole. Collecting those electron-hole pairs generates electric current.

Conventional solar cells generate one electron-hole pair ...

Study finds eating deep-fried food is associated with an increased risk of prostate cancer

2013-01-29

SEATTLE – Regular consumption of deep-fried foods such as French fries, fried chicken and doughnuts is associated with an increased risk of prostate cancer, and the effect appears to be slightly stronger with regard to more aggressive forms of the disease, according to a study by investigators at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

Corresponding author Janet L. Stanford, Ph.D., and colleagues Marni Stott-Miller, Ph.D., a postdoctoral research fellow and Marian Neuhouser, Ph.D., all of the Hutchinson Center's Public Health Sciences Division, have published their findings ...

Study shows climate change could affect onset and severity of flu seasons

2013-01-29

The American public can expect to add earlier and more severe flu seasons to the fallout from climate change, according to a research study published online Jan. 28 in PLOS Currents: Influenza.

A team of scientists led by Sherry Towers, research professor in the Mathematical, Computational and Modeling Sciences Center at Arizona State University, studied waves of influenza and climate patterns in the U.S. from the 1997-1998 season to the present.

The team's analysis, which used Centers for Disease Control data, indicates a pattern for both A and B strains: warm winters ...

Research: Military women may have higher risk for STIs

2013-01-29

As the number of women in the military increases, so does the need for improved gynecologic care. Military women may be more likely to engage in high-risk sexual practices, be less likely to consistently use barrier contraception, and, therefore, more likely to contract sexually transmitted infections (STIs), according to research recently released by a physician at Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island.

Vinita Goyal, MD, MPH, followed up earlier research into the rates of contraception use and unintended pregnancy by today's military women and veterans with her latest ...

USGS-NOAA: Climate change impacts to US coasts threaten public health, safety and economy

2013-01-29

According to a new technical report, the effects of climate change will continue to threaten the health and vitality of U.S. coastal communities' social, economic and natural systems.

The report, Coastal Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerabilities: a technical input to the 2013 National Climate Assessment, authored by leading scientists and experts, emphasizes the need for increased coordination and planning to ensure U.S. coastal communities are resilient against the effects of climate change.

The recently released report examines and describes climate change impacts ...

When food porn holds no allure: The science behind satiety

2013-01-29

New research from the University of British Columbia is shedding light on why enticing pictures of food affect us less when we're full.

"We've known that insulin plays a role in telling us we're satiated after eating, but the mechanism by which this happens is unclear," says Stephanie Borgland, an assistant professor in UBC's Dept. of Anesthesiology, Pharmacology and Therapeutics and the study's senior author.

In the new study published online this week in Nature Neuroscience, Borgland and colleagues found that insulin – prompted by a sweetened, high-fat meal – affects ...

Power helps you live the good life by bringing you closer to your true self

2013-01-29

How does being in a position of power at work, with friends, or in a romantic relationship influence well-being? While we might like to believe the stereotype that power leads to unhappiness or loneliness, new research indicates that this stereotype is largely untrue: Being in a position of power may actually make people happier.

Drawing on personality and power research, Yona Kifer of Tel Aviv University in Israel and colleagues hypothesized that holding a position of authority might enhance subjective well-being through an increased feeling of authenticity. The researchers ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

How sleep disruption impairs social memory: Oxytocin circuits reveal mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities

Natural compound from pomegranate leaves disrupts disease-causing amyloid

A depression treatment that once took eight weeks may work just as well in one

New study calls for personalized, tiered approach to postpartum care

The hidden breath of cities: Why we need to look closer at public fountains

Rewetting peatlands could unlock more effective carbon removal using biochar

Microplastics discovered in prostate tumors

ACES marks 150 years of the Morrow Plots, our nation's oldest research field

Physicists open door to future, hyper-efficient ‘orbitronic’ devices

$80 million supports research into exceptional longevity

Why the planet doesn’t dry out together: scientists solve a global climate puzzle

Global greening: The Earth’s green wave is shifting

You don't need to be very altruistic to stop an epidemic

Signs on Stone Age objects: Precursor to written language dates back 40,000 years

MIT study reveals climatic fingerprints of wildfires and volcanic eruptions

A shift from the sandlot to the travel team for youth sports

Hair-width LEDs could replace lasers

The hidden infections that refuse to go away: how household practices can stop deadly diseases

Ochsner MD Anderson uses groundbreaking TIL therapy to treat advanced melanoma in adults

A heatshield for ‘never-wet’ surfaces: Rice engineering team repels even near-boiling water with low-cost, scalable coating

Skills from being a birder may change—and benefit—your brain

Waterloo researchers turning plastic waste into vinegar

Measuring the expansion of the universe with cosmic fireworks

How horses whinny: Whistling while singing

US newborn hepatitis B virus vaccination rates

When influencers raise a glass, young viewers want to join them

Exposure to alcohol-related social media content and desire to drink among young adults

Access to dialysis facilities in socioeconomically advantaged and disadvantaged communities

Dietary patterns and indicators of cognitive function

New study shows dry powder inhalers can improve patient outcomes and lower environmental impact

[Press-News.org] New research will help shed light on role of Amazon forests in global carbon cycleBerkeley Lab scientists devise new tools for detecting previously unknown tree mortality