(Press-News.org) Cell division is serious business. Cells that divide incorrectly can lead to birth defects or set the stage for cancer. A new discovery from the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation has identified how two genes work together to make sure chromosomes are distributed properly when cells divide, providing new insights that could contribute to the future development of cancer treatments.

In a paper published in the new issue of the journal Science, OMRF researchers Dean Dawson, Ph.D., and Regis Meyer, Ph.D., reveal how two genes—known as Ipl1 and Mps1—are integral to the correct division of cells and life itself. If these "master regulator" genes can be controlled, it could help physicians target and destroy pre-cancerous cells or prevent birth defects.

"The human body begins as a single cell. Through the process of cell division, we come to be composed of trillions of cells. And every one of those divisions must be perfect so that each new cell inherits a correct set of chromosomes," said Dawson, the senior author of the new study. "Given the sheer number of cell divisions involved, it's amazing there aren't more mistakes. My laboratory is interested in dissecting the machine that does this so well and understanding why it fails in some rare cases."

"When cells divide, they first duplicate the DNA, which is carried on the chromosomes," he said. "Think of the cell kind of like a factory. First it duplicates the chromosomes—so that each one becomes a pair, then it lines them up so the pairs can be pulled apart—with one copy going to each daughter cell. This way, one perfect set goes to each new daughter cell, ensuring that the two new cells that come from the division have full sets of the DNA."

To do that properly, each chromosome is attached to a kind of cellular winch, he said. Just before the cells divide, the winches drag the chromosomes into the new daughter cells. In the laboratory, Dawson used high-powered microscopes to observe the process of cell division in yeast cells. But as he watched the cells dividing, Meyer and Dawson observed something unexpected: The cells kept making mistakes as they attached the chromosomes to the winches.

"About 80 percent of the time, chromosomes would get hooked to the wrong winch, and the cell would begin pulling both copies off to the same side instead of pulling one towards each new daughter cell," he said. "If the cell divided like that, you'd have all sorts of problems. The cells that fail to receive a chromosome will probably die. The cell that receives too many is likely in trouble. Inappropriate chromosome numbers is a leading cause of birth defects and is a common feature of tumor cells."

However, with further study, Dawson discovered that the Ipl1 and Mps1 genes act as quality controllers. When a chromosome gets pulled to the wrong side, one gene disconnects the winch, then the other gene connects to a new winch. "These genes are master regulators. If they're removed, the entire process goes haywire," Dawson said.

While the genes are responsible for correcting the mistakes that could lead to cancer, researchers have found that cancer cells with abnormal numbers of chromosomes are even more dependent on Ipl1 and Mps1 than normal cells, Dawson said. Several groups are investigating ways to target the genes as a potential anti-cancer treatment.

"We think this research is going to be useful in designing those compounds," he said. "When you understand exactly how the process works, you know how to better craft a treatment."

###

Gary Gorbsky, Ph.D., chair of OMRF's Cell Cycle and Cancer Biology Research Program, says the finding casts new light on processes that are vital to life. "Dr. Dawson is helping to 'write the manual' for cell division. Basic research is important because we cannot understand what goes wrong when cells divide until we understand how the machinery is supposed to function."

Paul Straight, Ph.D., and Mark Winey, Ph.D., of the University of Colorado contributed to the research. The project was funded by National Science Foundation award 0950005 from the Division of Molecular and Cellular Biosciences and grant R01GM087377 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, part of the National Institutes of Health.

Understanding 'master regulator' genes could lead to better cancer treatments

2013-02-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Ozone depletion trumps greenhouse gas increase in jet-stream shift

2013-02-01

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- Depletion of Antarctic ozone is a more important factor than increasing greenhouse gases in shifting the Southern Hemisphere jet stream in a southward direction, according to researchers at Penn State.

"Previous research suggests that this southward shift in the jet stream has contributed to changes in ocean circulation patterns and precipitation patterns in the Southern Hemisphere, both of which can have important impacts on people's livelihoods," said Sukyoung Lee, professor of meteorology.

According to Lee, based on modeling studies, both ...

Diabetes distresses bone marrow stem cells by damaging their microenvironment

2013-02-01

New research has shown the presence of a disease affecting small blood vessels, known as microangiopathy, in the bone marrow of diabetic patients. While it is well known that microangiopathy is the cause of renal damage, blindness and heart attacks in patients with diabetes, this is the first time that a reduction of the smallest blood vessels has been shown in bone marrow, the tissue contained inside the bones and the main source of stem cells.

These precious cells not only replace old blood cells but also exert an important reparative function after acute injuries ...

Transition in cell type parallels treatment response, disease progression in breast cancer

2013-02-01

A process that normally occurs in developing embryos – the changing of one basic cell type into another – has also been suspected of playing a role in cancer metastasis. Now a study from Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Cancer Center researchers has associated this process, called epithelial-mesenchymal transition or EMT, with disease progression and treatment response in breast cancer patients. The report also identifies underlying mechanisms that someday may become therapeutic targets.

"Until now, EMT had only been modeled in experimental systems, but its clinical ...

Training bystanders to spot drug overdoses can reduce deaths

2013-02-01

Overdoses of opioid drugs are a major cause of emergency hospital admissions and preventable death in many countries. In Massachusetts, annual opioid-related overdose deaths have exceeded motor vehicle deaths since 2005, so several strategies have been introduced to tackle this growing problem.

For example, overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND) programs train drug users, their families and friends, and potential bystanders to prevent, recognize, and respond to opioid overdoses. OEND participants are trained to recognize signs of overdose, seek help, rescue ...

Medical school gift restriction policies linked to subsequent prescribing behavior

2013-02-01

Medical school policies that restrict gifts to physicians from the pharmaceutical and device industries are becoming increasingly common, but the effect of such policies on physician prescribing behaviour after graduation into clinical practice is unknown.

So a team of US researchers set out to examine whether attending a medical school with a gift restriction policy affected subsequent prescribing of three newly marketed psychotropic (stimulant, antidepressant, and antipsychotic) drugs.

They identified 14 US medical schools with an active gift restriction policy ...

Planting trees may not reverse climate change but it will help locally

2013-02-01

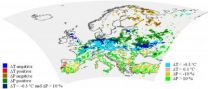

Afforestation, planting trees in an area where there have previously been no trees, can reduce the effect of climate change by cooling temperate regions finds a study in BioMed Central's open access journal Carbon Balance and Management. Afforestation would lead to cooler and wetter summers by the end of this century.

Without check climate change is projected to lead to summer droughts and winter floods across Europe. Using REMO, the regional climate model of the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, researchers tested what would happen to climate change in 100 years ...

New stroke gene discovery could lead to tailored treatments

2013-02-01

An international study led by King's College London has identified a new genetic variant associated with stroke. By exploring the genetic variants linked with blood clotting – a process that can lead to a stroke – scientists have discovered a gene which is associated with large vessel and cardioembolic stroke but has no connection to small vessel stroke.

Published in the journal Annals of Neurology, the study provides a potential new target for treatment and highlights genetic differences between different types of stroke, demonstrating the need for tailored treatments. ...

Discovery in synthetic biology takes us a step closer to new 'industrial revolution'

2013-02-01

The scientists, from Imperial College London, say their research brings them another step closer to a new kind of industrial revolution, where parts for these biological factories could be mass-produced. These factories have a wealth of applications including better drug delivery treatments for patients, enhancements in the way that minerals are mined from deep underground and advances in the production of biofuels.

Professor Paul Freemont, Co- Director of the Centre for Synthetic Biology and Innovation at Imperial College London and principle co-investigator of the study, ...

The genome of rock pigeon reveals the origin of pigeons and the molecular traits

2013-02-01

January 31, 2013, Shenzhen, China – In a study published today in Science, researchers from University of Utah, BGI, and other institutes have completed the genome sequencing of rock pigeon, Columba livia, among the most common and varied bird species on Earth. The work reveals the evolutionary secrets of pigeons and opens a new way for researchers to study the genetic traits controlling pigeons' splendid diversity. The findings also help to fill the genetic gaps in exploiting pigeon as a model for the molecular genetic basis of avian variation.

People are quite familiar ...

Placental blood flow can influence malaria during pregnancy

2013-02-01

Malaria in pregnancy causes a range of adverse effects, including abortions, stillbirths, premature delivery and low infant birth weight. Many of these effects are thought to derive from a placental inflammatory response resulting from interaction of infected red blood cells with the placental tissue. In a study published in the latest issue of the journal PLOS Pathogen*, a researchers' team led by Carlos Penha-Gonçalves at the Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência (IGC), Portugal, observed, for the first time, the mouse placental circulation and showed how it can influence the ...