(Press-News.org) PHILADELPHIA — The recently published genome sequences of seven well-studied ant species are opening up new vistas for biology and medicine. A detailed look at molecular mechanisms that underlie the complex behavioral differences in two worker castes in the Florida carpenter ant, Camponotus floridanus, has revealed a link to epigenetics. This is the study of how the expression or suppression of particular genes by chemical modifications affects an organism's physical characteristics, development, and behavior. Epigenetic processes not only play a significant role in many diseases, but are also involved in longevity and aging.

Interdisciplinary research teams led by Shelley Berger, PhD, from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, in collaboration with teams led by Danny Reinberg from New York University and Juergen Liebig from Arizona State University, describe their work in Genome Research. The group found that epigenetic regulation is key to distinguishing one caste, the "majors", as brawny Amazons of the carpenter ant colony, compared to the "minors", their smaller, brainier sisters. These two castes have the same genes, but strikingly distinct behaviors and shape.

Ants, as well as termites and some bees and wasps, are eusocial species that organize themselves into rigid caste-based societies, or colonies, in which only one queen and a small contingent of male ants are usually fertile and reproduce. The rest of a colony is composed of functionally sterile females that are divided into worker castes that perform specialized roles such as foragers, soldiers, and caretakers. In Camponotus floridanus, there are two worker castes that are physically and behaviorally different, yet genetically very similar.

Lead author Daniel F. Simola, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in the Penn Department of Cell and Developmental Biology, explains that "the major is also called a soldier, and it has a much larger head, so the force of its mandibles can break larger prey. It does more nest and colony defense."

The minor caste, on the other hand, is smaller and more numerous. "They do most of the nursing within a colony, take care of the young, and they will also go out and collect most of the food," says Simola. "On average, 75 to 80 percent of the foraging activity is done by the minors." The minor also has a considerably shorter lifespan than the major caste, making the ant castes a good model for longevity studies as well as behavioral studies.

But how do such marked differences arise when both the major and the minor castes share the same genome? "For all intents and purposes, those two castes are identical when it comes to their gene sequences," notes senior author Berger, professor of Cell and Developmental Biology. "The two castes are a perfect situation to understand how epigenetics, how regulation 'above' genes, plays a role in establishing these dramatic differences in a whole organism."

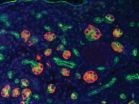

To understand how caste differences arise, the team examined the role of modifications of histones (protein complexes around which DNA strands are wrapped in a cell's nucleus) throughout the Camponotus floridanus genome, producing the first genome-wide epigenetic maps of genome structure in a social insect. Histones can be altered by the addition of small chemical groups, which affect the expression of genes. Therefore, specific histone modifications can create dramatic differences between genetically similar individuals, such as the physical and behavioral differences between ant castes.

"These chemical modifications of histones alter how compact the genome is in a certain region," Simola explains. "Certain modifications allow DNA to open up more, and some of them to close DNA more. This, in turn, affects how genes get expressed, or turned on, to make proteins. These modifications establish specific features of different tissues within an individual, so we asked whether there are also overall differences in histone modifications between the brawny majors and the brainy minors that might alter specific features of the whole organism, such as behavior."

In examining several different histone modifications, the team found a number of distinct differences between the major and minor castes. Simola states that the most notable modification, "both discriminates the two castes from each other and correlates well with the expression levels of different genes between the castes. And if you look at which genes are being expressed between these two castes, these genes correspond very nicely to the brainy versus brawny idea. In the majors we find that genes that are involved in muscle development are expressed at a higher level, whereas in the minors, many genes involved in brain development and neurotransmission are expressed at a higher level."

These changes in histone modifications between ant castes are likely caused by a regulator gene, called CBP, that has "already been implicated in aspects of learning and behavior by genetic studies in mice and in certain human diseases," Berger says. "The idea is that the same CBP regulator and histone modification are involved in a learned behavior in ants – foraging – mainly in the brainy minor caste, to establish a pattern of gene regulation that leads to neuronal patterning for figuring out where food is and being able to bring the food back to the nest."

Simola notes that "we know from mouse studies that if you inactivate or delete the CBP regulator, it actually leads to significant learning deficits in addition to craniofacial muscular malformations. So from mammalian studies, it's clear this is an important protein involved in learning and memory."

These findings have established the crucial role of genome structure in general, and histone modifications in particular, in determining the acquisition of organism-level characteristics in ant castes. The research team is looking ahead to expand the work by manipulating the expression of the CBP regulator in ants to observe effects on caste development and behavior. They also hope to refine the technique of mapping histone modifications so that specific tissues, such as a brain from a single ant, can be analyzed, rather than using pooled samples, as in the current study.

Berger observes that all of the genes known to be major epigenetic regulators in mammals are conserved in ants, which makes them "a fantastic model for studying behavior and longevity. Ants provide an extraordinary opportunity to explore and understand the epigenetic processes that underlie many human diseases and the aging process."

INFORMATION:

Berger is also the director of the Penn Epigenetics Program. The research was supported by a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Collaborative Innovation Award, a postdoctoral training grant from the Penn Department of Cell and Developmental Biology, and a postdoctoral fellowship from the Helen Hay Whitney Foundation.

Penn Medicine is one of the world's leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, and excellence in patient care. Penn Medicine consists of the Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (founded in 1765 as the nation's first medical school) and the University of Pennsylvania Health System, which together form a $4.3 billion enterprise.

The Perelman School of Medicine is currently ranked #2 in U.S. News & World Report's survey of research-oriented medical schools. The School is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $479.3 million awarded in the 2011 fiscal year.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System's patient care facilities include: The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania -- recognized as one of the nation's top "Honor Roll" hospitals by U.S. News & World Report; Penn Presbyterian Medical Center; and Pennsylvania Hospital — the nation's first hospital, founded in 1751. Penn Medicine also includes additional patient care facilities and services throughout the Philadelphia region.

Penn Medicine is committed to improving lives and health through a variety of community-based programs and activities. In fiscal year 2011, Penn Medicine provided $854 million to benefit our community.

Epigenetics shapes fate of brain vs. brawn castes in carpenter ants

2013-02-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Discovering cell surface proteins' behavior

2013-02-13

Contact:

Bingyun Sun, 778.782.9097, bingyun_sun@sfu.ca

Carol Thorbes, PAMR, 778.782.3035, cthorbes@sfu.ca

Simon Fraser University is Canada's top-ranked comprehensive university and one of the top 50 universities in the world under 50 years old. With campuses in Vancouver, Burnaby and Surrey, B.C., SFU engages actively with the community in its research and teaching, delivers almost 150 programs to more than 30,000 students, and has more than 120,000 alumni in 130 countries.

Simon Fraser University: Engaging Students. Engaging Research. Engaging Communities.

...

Southwest regional warming likely cause of pinyon pine cone decline, says CU study

2013-02-13

Creeping climate change in the Southwest appears to be having a negative effect on pinyon pine reproduction, a finding with implications for wildlife species sharing the same woodland ecosystems, says a University of Colorado Boulder-led study.

The new study showed that pinyon pine seed cone production declined by an average of about 40 percent at nine study sites in New Mexico and northwestern Oklahoma over the past four decades, said CU-Boulder doctoral student Miranda Redmond, who led the study. The biggest declines in pinyon pine seed cone reproduction were at the ...

Building a biochemistry lab on a chip

2013-02-13

Miniaturized laboratory-on-chip systems promise rapid, sensitive, and multiplexed detection of biological samples for medical diagnostics, drug discovery, and high-throughput screening. Using micro-fabrication techniques and incorporating a unique design of transistor-based heating, researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign are further advancing the use of silicon transistor and electronics into chemistry and biology for point-of-care diagnostics.

Lab-on-a-chip technologies are attractive as they require fewer reagents, have lower detection limits, ...

Study shows that problem-solving training helps mothers cope with child's cancer diagnosis

2013-02-13

A multi-site clinical trial including the University of Colorado Cancer Center shows that the benefit of Bright IDEAS problem-solving skills training goes beyond teaching parents to navigate the complex medical, educational, and other systems that accompany a child's diagnosis of cancer – the training also leads to durable reduction in mothers' levels of anxiety and symptoms of posttraumatic stress, and improves overall coping with a child's illness. Results of the study were published online last week in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

"Earlier research shows that ...

Molecular master switch for pancreatic cancer identified, potential predictor of treatment outcome

2013-02-13

PHILADELPHIA – A recently described master regulator protein may explain the development of aberrant cell growth in the pancreas spurred by inflammation

A team from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania profiled gene expression of mouse pancreatic ductal and duct-like cells from different states - embryonic development, acute pancreatitis and K-ras mutation-driven carcinogenesis - to find the molecular regulation of these processes.

Broadly speaking, two cellular compartments are important in a normal pancreas, endocrine cells, which produce ...

Marketing technique: Activating gender stereotypes just to knock 'em down

2013-02-13

In certain circles, such as publishing, it has been well-documented that female authors have taken male pen names to attract a larger audience and/or get their book published. But should marketers actually highlight gender and activate stereotypes to sell more products?

A new study by USC Marshall Professor Valerie Folkes and Ohio State University Professor Shashi Matta looks at the issue of product perception of consumers through the lens of gender stereotypes. The researchers conclude that while traditional gender stereotypes can still have a significant influence on ...

Cities can reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 70 percent, says U of T researcher

2013-02-13

TORONTO, ON – Cities around the world can significantly reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by implementing aggressive but practical policy changes, says a new study by University of Toronto Civil Engineering Professor Chris Kennedy and World Bank climate change specialist Lorraine Sugar, one of Kennedy's former students.

Kennedy and Sugar make the claim in 'A low carbon infrastructure plan for Toronto, Canada,' published in the latest issue of The Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering. The paper aims to show how cities can make a positive difference using realistic, ...

Stanford scientist uncovers the reproductive workings of a harvester ant dynasty

2013-02-13

Ants are just about everywhere you look, and yet it's largely unknown how they manage to be so ubiquitous. Scientists have understood the carnal mechanism of ant reproduction, but until now have known little of how successful the daughters of a colony are when they attempt to found new colonies.

For the first time, Stanford biologists have been able to identify specific parent ants and their own children in wild ant colonies, making it possible to study reproduction trends.

And in a remarkable display of longevity, an original queen ant was found to be producing new ...

Major clinical trial finds no link between genetic risk factors and 2 top wet AMD treatments

2013-02-13

SAN FRANCISCO – February 12, 2013 – New findings from a landmark clinical trial show that although certain gene variants may predict whether a person is likely to develop age-related macular degeneration (AMD), a potentially blinding eye disease that afflicts more than nine million Americans, these genes do not predict how patients will respond to Lucentis™ and Avastin™, the two medications most widely used to treat the "wet" form of AMD. This new data from the Comparison of AMD Treatment Trials (CATT), published online in Ophthalmology, the journal of the American Academy ...

Explosive breakthrough in research on molecular recognition

2013-02-13

Edmonton—Ever wonder how sometimes people still get through security with explosives on their person? Research done in the University of Alberta's Department of Chemical and Materials Engineering has revealed a new way to better detect these molecules associated with explosive mixtures.

A team of researchers including post-doctoral fellows Seonghwan Kim, Dongkyu Lee and Xuchen Liu, with research associate Charles Van Neste, visiting professor, Sangmin Jeon from the Pohang University of Science and Technology (South Korea), and Department of Chemical and Materials Engineering ...