(Press-News.org) This press release is available in German.

Street lamps, traffic lights and lighting from homes are causing a rise in our night-time light levels. For some time now, scientists have suspected that artificial light in our towns and cities at night could affect plants, animals and us, humans, too. Studies, however, that have tested this influence directly are few. Scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology in Radolfzell, Germany, recently investigated how light conditions in urban areas at night affect European blackbirds (Turdus merula). They found that animals exposed to low night-time light intensities, comparable to those found in cities, develop their reproductive system earlier: their testosterone levels rise and their testes mature earlier in the year. They also begin to sing and to moult earlier. The ever-present light pollution in cities may therefore exert a major influence on the seasonal rhythm of urban animals.

For many species, the seasonal change in day length is one of the most important environmental signals in controlling daytime rhythms (e.g. sleep-wake cycles) and seasonal ones (e.g. breeding season). People have long been exploiting this in areas such as agriculture: egg production in battery farming can be increased by altering the length of day with the help of artificial lighting.

City-dwelling animals are now not only exposed to natural light conditions, at times they also experience extreme levels of lighting as a result of artificial light. But what effect does artificial light have on the time-of-day and seasonal organisation of these urban animals? To answer this question, it is first crucial to know what light intensities the birds are actually experiencing at night. Therefore, a group of scientists working with Jesko Partecke from the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology tagged several urban blackbirds with light loggers to measure the average light intensities the birds were exposed to during the night. "The intensities were very low – 0.2 lux. That's just one-thirtieth of the light emanating from a typical street lamp," says the scientist.

Yet even such low values are sufficient to make the gonads of male blackbirds mature earlier. The scientists exposed wild-caught city and forest blackbirds to lighting intensities of 0.3 lux at night over a period of ten months. "The results were astonishing: The birds' gonads grew on average almost a month earlier than those of animals that slept in the dark," explains Partecke. The scientists also measured the level of testosterone in the birds' blood as another indicator of the animals' readiness for breeding. They found that the level rose earlier if the birds had been exposed to light at night. Song activity also got out of rhythm as a result of the low night-time light intensity; the animals began singing around one hour earlier. "All of this indicates that, from a seasonal perspective, the animals are ready to breed earlier," explains Partecke. However, animals living with night-time light not only exhibited an advanced onset of breeding, they also moulted towards the end of the breeding season a lot earlier than birds that spent their nights in the dark. "These findings are clear evidence that the artificial light we find in towns and cities can dramatically change the seasonal organisation of wild animals.

The scientists do not yet know what causes the advanced onset of breeding. It could be that the artificial night-time light has the effect of extending the day length for the animals. Or perhaps the light makes the birds continue hunting for food at night and put the additional energy into reproduction. Equally, the light may also influence the animals' metabolism and the altered metabolism might be what causes earlier gonad growth. Birds are more active in the daytime if they are exposed to light at night.

Nor is it clear whether the city blackbirds' advanced breeding offers an advantage or whether it is merely an unintended side effect of the lighting. "Blackbirds in the city are able to breed earlier in the year due to the artificial light and can produce more young in a year as a result," explains Partecke. "But only if the nestlings have access to enough food." Otherwise, the advanced onset of breeding could turn out to be an evolutionary disadvantage for blackbirds. With this in mind, the next aspect the scientists plan to study in their field research is the impact of night-time light in urban areas on the birds' fitness.

INFORMATION:

Original publication

Davide Dominoni, Michael Quetting and Jesko Partecke

Artificial light at night advances avian reproductive physiology

Proceedings of the Royal Society Series B, February 13, 2013

Blackbirds in the spotlight

City birds that experience light at night are ready to breed earlier than their rural cousins

2013-02-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Copper depletion therapy keeps high-risk triple-negative breast cancer at bay

2013-02-13

NEW YORK (February 13, 2013) -- An anti-copper drug compound that disables the ability of bone marrow cells from setting up a "home" in organs to receive and nurture migrating cancer tumor cells has shown surprising benefit in one of the most difficult-to-treat forms of cancer -- high-risk triple-negative breast cancer.

The median survival for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer patients is historically nine months. However, results of a new phase II clinical trial conducted by researchers at Weill Cornell Medical College and reported in the Annals of Oncology shows ...

UNC researchers discover gene that suppresses herpesviruses

2013-02-13

Chapel Hill, NC – Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) hide within the worldwide human population. While dormant in the vast majority of those infected, these active herpesviruses can develop into several forms of cancer. In an effort to understand and eventually develop treatments for these viruses, researchers at the University of North Carolina have identified a family of human genes known as Tousled-like kinases (TLKs) that play a key role in the suppression and activation of these viruses.

In a paper published by Cell Host ...

'A drop of ink on the luminous sky'

2013-02-13

This part of the constellation of Sagittarius (The Archer) is one of the richest star fields in the whole sky -- the Large Sagittarius Star Cloud. The huge number of stars that light up this region dramatically emphasise the blackness of dark clouds like Barnard 86, which appears at the centre of this new picture from the Wide Field Imager, an instrument mounted on the MPG/ESO 2.2-metre telescope at ESO's La Silla Observatory in Chile.

This object, a small, isolated dark nebula known as a Bok globule [1], was described as "a drop of ink on the luminous sky" by its discoverer ...

Study suggests infant deaths can be prevented

2013-02-13

(TORONTO, Canada – Feb. 13, 2013) – An international team of tropical medicine researchers have discovered a potential method for preventing low birth weight in babies born to pregnant women who are exposed to malaria. Low birth weight is the leading cause of infant death globally.

The findings of Malaria Impairs Placental Vascular Development, published today online ahead of print in Cell Host & Microbe, showed that the protein C5a and its receptor, C5aR, seem to control the blood vessel development in the mother's placenta. Without adequate blood vessels in the placenta, ...

Carnegie Mellon brain imaging research shows how unconscious processing improves decision-making

2013-02-13

PITTSBURGH—When faced with a difficult decision, it is often suggested to "sleep on it" or take a break from thinking about the decision in order to gain clarity.

But new brain imaging research from Carnegie Mellon University, published in the journal "Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience," finds that the brain regions responsible for making decisions continue to be active even when the conscious brain is distracted with a different task. The research provides some of the first evidence showing how the brain unconsciously processes decision information in ways ...

Study in mice yields Angelman advance

2013-02-13

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — In a new study in mice, a scientific collaboration centered at Brown University lays out in unprecedented detail a neurological signaling breakdown in Angelman syndrome, a disorder that affects thousands of children each year, characterized by developmental delay, seizures, and other problems. With the new understanding, the team demonstrated how a synthesized, peptide-like compound called CN2097 works to restore neural functions impaired by the disease.

"I think we are really beginning to understand what's going wrong. That's what's ...

A neural basis for benefits of meditation

2013-02-13

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Why does training in mindfulness meditation help patients manage chronic pain and depression? In a newly published neurophysiological review, Brown University scientists propose that mindfulness practitioners gain enhanced control over sensory cortical alpha rhythms that help regulate how the brain processes and filters sensations, including pain, and memories such as depressive cognitions.

The proposal, based on published experimental results and a validated computer simulation of neural networks, derives its mechanistic framework ...

Wetland trees a significant overlooked source of methane, study finds

2013-02-13

Wetlands are a well-established and prolific source of atmospheric methane. Yet despite an abundance of seething swamps and flooded forests in the tropics, ground-based measurements of methane have fallen well short of the quantities detected in tropical air by satellites.

In 2011, Sunitha Pangala, a PhD student at The Open University, who is co-supervised by University of Bristol researcher Dr Ed Hornibrook, spent several weeks in a forested peat swamp in Borneo with colleague Sam Moore, assessing whether soil methane might be escaping to the atmosphere by an alternative ...

3 'Bigfoot' genomes sequenced in 5-year DNA study

2013-02-13

Dallas, Feb. 13--The multidisciplinary team of scientists, who on November 24, 2012 announced the results of their five-year long study of DNA samples from a novel hominin species, commonly known as "Bigfoot" or "Sasquatch," publishes their peer-reviewed findings today in the DeNovo Journal of Science (http://www.denovojournal.com). The study, which sequenced three whole Sasquatch nuclear genomes, shows that the legendary Sasquatch is extant in North America and is a human relative that arose approximately 13,000 years ago and is hypothesized to be a hybrid cross of modern ...

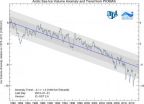

European satellite confirms UW numbers: Arctic Ocean is on thin ice

2013-02-13

The September 2012 record low in Arctic sea-ice extent was big news, but a missing piece of the puzzle was lurking below the ocean's surface. What volume of ice floats on Arctic waters? And how does that compare to previous summers? These are difficult but important questions, because how much ice actually remains suggests how vulnerable the ice pack will be to more warming.

New satellite observations confirm a University of Washington analysis that for the past three years has produced widely quoted estimates of Arctic sea-ice volume. Findings based on observations from ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Marshall University, Intermed Labs announce new neurosurgical innovation to advance deep brain stimulation technology

Preclinical study reveals new cream may prevent or slow growth of some common skin cancers

Stanley Family Foundation renews commitment to accelerate psychiatric research at Broad Institute

What happens when patients stop taking GLP-1 drugs? New Cleveland Clinic study reveals real world insights

American Meteorological Society responds to NSF regarding the future of NCAR

Beneath Great Salt Lake playa: Scientists uncover patchwork of fresh and salty groundwater

Fall prevention clinics for older adults provide a strong return on investment

People's opinions can shape how negative experiences feel

USC study reveals differences in early Alzheimer’s brain markers across diverse populations

300 million years of hidden genetic instructions shaping plant evolution revealed

High-fat diets cause gut bacteria to enter brain, Emory study finds

Teens and young adults with ADHD and substance use disorder face treatment gap

Instead of tracking wolves to prey, ravens remember — and revisit — common kill sites

Ravens don’t follow wolves to dinner – they remember where the food is

Mapping the lifelong behavior of killifish reveals an architecture of vertebrate aging

Designing for hard and brittle lithium needles may lead to safer batteries

Inside the brains of seals and sea lions with complex vocal behavior learning

Watching a lifetime in motion reveals the architecture of aging

Rapid evolution can ‘rescue’ species from climate change

Molecular garbage on tumors makes easy target for antibody drugs

New strategy intercepts pancreatic cancer by eliminating microscopic lesions before they become cancer

Embryogenesis in 4D: a developmental atlas for genes and cells

CNIO research links fertility with immune cells in the brain

Why do lithium-ion batteries fail? Scientists find clues in microscopic metal 'thorns'

Surface treatment of wood may keep harmful bacteria at bay

Carsten Bönnemann, MD, joins St. Jude to expand research on pediatric catastrophic neurological disorders

Women use professional and social networks to push past the glass ceiling

Trial finds vitamin D supplements don’t reduce covid severity but could reduce long COVID risk

Personalized support program improves smoking cessation for cervical cancer survivors

Adverse childhood experiences and treatment-resistant depression

[Press-News.org] Blackbirds in the spotlightCity birds that experience light at night are ready to breed earlier than their rural cousins