(Press-News.org) A single mutation in a moth gene has been shown to be able to produce an entirely new scent. This has been shown in a new study led by researchers from Lund University in Sweden. In the long run, the researchers say that the results could contribute to tailored production of pheromones for pest control.

Male moths can pick up the scent of a female moth from a distance of several hundred metres. The females produce sexual pheromones – scent substances that guide the males to them. There are around 180 000 species of moth and butterfly in the world, and most of them communicate using pheromones. Small differences between the different scents enable the males to find females of their own species.

Researchers at Lund University have previously shown that new species of moth can evolve as a result of changes in the female moths' scent. Now the researchers have published a study on how these changes come about at genetic level.

"Our results show that a single mutation, which leads to the substitution of a critical amino acid, is sufficient to create a new pheromone blend", says Professor Christer Löfstedt from the Department of Biology at Lund University.

The study has been carried out together with researchers in Japan and focuses on a moth genus called Ostrinia. The researchers have studied one of the genes that control the production of pheromones. It is in this context that the mutation and the substituted amino acid in an enzyme have shown to result in a new scent substance. The enzyme is active in the process that converts fatty acids into alcohols, which constitute the ingredients in many moth scents.

"Pheromones are already one of the most frequently used methods for environmentally friendly pest control", says Christer Löfstedt. "With this knowledge, we hope in the future to be able to tailor the production of pheromones in yeast cells and plants to develop a cheap and environmentally friendly production process."

###

The study has been published in the scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2013/02/13/1208706110

For more information, contact:

Professor Christer Löfstedt

Department of Biology, Lund University, Sweden

tel. +46 46 222 93 38

Christer.Lofstedt@biol.lu.se END

Towards a new moth perfume

2013-02-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Radio telescope, GPS use ionosphere to detect nuclear tests

2013-02-19

WASHINGTON--U.S. Naval Research Laboratory radio astronomer, Joseph Helmboldt, Ph.D., and researchers at Ohio State University Department of Civil, Environmental and Geodetic Engineering analyzed radio telescope interferometry and Global Positioning Satellite (GPS) data recorded of the ionosphere during one of the last underground nuclear explosions (UNEs) in the U.S., codenamed Hunters Trophy.

Situated in the Plains of San Agustin, 50 miles west of Socorro, New Mexico, twenty-seven 25-meter parabolic dish antennas collectively make up the National Radio Astronomy Observatory's ...

Private Security Industry must be made transparent and accountable, study concludes

2013-02-19

The true cost of war is being masked by the secretive and largely unaccountable activities of a private security industry, according to a new study.

These invisible costs of war – both in terms of casualties and financial resources – are not reported and are hard to find because contractors are not subject to the same reporting structures and laws as the regular military, and many of their activities are protected from Freedom of Information requests.

Private security firms – usually run by former senior figures in the military, civil service or politics – are increasingly ...

Could an old antidepressant treat sickle cell disease?

2013-02-19

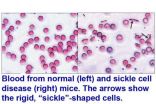

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — An antidepressant drug used since the 1960s may also hold promise for treating sickle cell disease, according to a surprising new finding made in mice and human red blood cells by a team from the University of Michigan Medical School.

The discovery that tranylcypromine, or TCP, can essentially reverse the effects of sickle cell disease was made by U-M scientists who have spent more than three decades studying the basic biology of the condition, with funding from the National Institutes of Health.

Their findings, published in Nature Medicine, pave ...

Buying ad time just got easier

2013-02-19

EAST LANSING, Mich. — Today's consumers switch between media forms so often – from TV to laptops to smart phones – that capturing their attention with advertising has gone, as one CEO explained, from shooting fish in a barrel to shooting minnows.

Now, a Michigan State University business scholar and colleagues have developed the most accurate model yet for targeting those fast-moving minnows. The research-based model predicts when during the day people use the varying forms of media and even when they are using two or more at a time, an increasingly common practice known ...

Could a computer on the police beat prevent violence?

2013-02-19

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — As cities across America work to reduce violence in tight budget times, new research shows how they might be able to target their efforts and police attention – with the help of high-powered computers and loads of data.

In a newly published paper, University of Michigan Medical School researchers and their colleagues have used real police data from Boston to demonstrate the promise of computer models in zeroing in on violent areas.

They combined and analyzed information in small geographic units, on police reports, drug offenses, and alcohol availability ...

Russian fireball largest ever detected by CTBTO's infrasound sensors

2013-02-19

Infrasonic waves from the meteor that broke up over Russia's Ural mountains last week were the largest ever recorded by the CTBTO's International Monitoring System. Infrasound is low frequency sound with a range of less than 10 Hz. The blast was detected by 17 infrasound stations in the CTBTO's network, which tracks atomic blasts across the planet. The furthest station to record the sub-audible sound was 15,000km away in Antarctica.

The origin of the low frequency sound waves from the blast was estimated at 03:22 GMT on 15 February 2013. People cannot hear the low frequency ...

Researchers create semiconductor 'nano-shish-kebabs' with potential for 3-D technologies

2013-02-19

Researchers at North Carolina State University have developed a new type of nanoscale structure that resembles a "nano-shish-kebab," consisting of multiple two-dimensional nanosheets that appear to be impaled upon a one-dimensional nanowire. But looks can be deceiving, as the nanowire and nanosheets are actually a single, three-dimensional structure consisting of a single, seamless series of germanium sulfide (GeS) crystals. The structure holds promise for use in the creation of new, three-dimensional (3-D) technologies.

The researchers believe this is the first engineered ...

Theory of crystal formation complete again

2013-02-19

Exactly how a crystal forms from solution is a problem that has occupied scientists for decades. Researchers at Eindhoven University of Technology (TU/e), together with researchers from Germany and the USA, are now presenting the missing piece. This classical theory of crystal formation, which occurs widely in nature and in the chemical industry, was under fire for some years, but is saved now. The team made this breakthrough by detailed study of the crystallization of the mineral calcium phosphate –the major component of our bones. The team published their findings yesterday ...

New study shows how seals sleep with only half their brain at a time

2013-02-19

TORONTO, ON – A new study led by an international team of biologists has identified some of the brain chemicals that allow seals to sleep with half of their brain at a time.

The study was published this month in the Journal of Neuroscience and was headed by scientists at UCLA and the University of Toronto. It identified the chemical cues that allow the seal brain to remain half awake and asleep. Findings from this study may explain the biological mechanisms that enable the brain to remain alert during waking hours and go off-line during sleep.

"Seals do something biologically ...

We know when we're being lazy thinkers

2013-02-19

Are we intellectually lazy? Yes we are, but we do know when we take the easy way out, according to a new study by Wim De Neys and colleagues, from the CNRS in France. Contrary to what psychologists believe, we are aware that we occasionally answer easier questions rather than the more complex ones we were asked, and we are also less confident about our answers when we do. The work is published online in Springer's journal Psychonomic Bulletin & Review.

Research to date on human thinking suggests that our judgment is often biased because we are intellectually lazy, or ...