(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Understanding exactly how droplets and bubbles stick to surfaces — everything from dew on blades of grass to the water droplets that form on condensing coils after steam drives a turbine in a power plant — is a "100-year-old problem" that has eluded experimental answers, says MIT's Kripa Varanasi. Furthermore, it's a question with implications for everything from how to improve power-plant efficiency to how to reduce fogging on windshields.

Now this longstanding problem has finally been licked, Varanasi says, in research he conducted with graduate student Adam Paxson that is described this week in the journal Nature Communications. They achieved the feat using a modified version of a scanning electron microscope in which the dynamic behavior of droplets on surfaces at any angle could be observed in action at high resolution.

Previous attempts to study droplet adhesion have been static — using drops of a polymer that are allowed to harden and then sliced in cross-section — or have been done only at very low resolution. The ability to observe the process in close-up detail and in full motion is an unprecedented feat, says Varanasi, the Doherty Associate Professor of Ocean Utilization.

Normally, scanning electron microscopes observe materials on a fixed horizontal stage and under a strong vacuum, which causes water to evaporate instantly. The MIT team was able to adapt the equipment to operate with a weaker vacuum, and with the ability to change the surface angle and to push and pull droplets across the surface with a tiny wire.

Paxson and Varanasi found that a key factor in determining whether a droplet sticks to the surface is the angle of the droplet's leading and trailing edges relative to the surface. Nobody had been able to observe these angles dynamically at microscale before, while theorists had not predicted their importance.

The MIT researchers also found that on rough surfaces, surface texture is crucial to adhesion. Surprisingly, they found that too much roughness can make droplets stick more — contrary to the widely held belief that greater roughness always improves a surface's ability to shed water. It all depends on the details of the texture, they found.

For many applications, it's important that droplets fall away from a condensing surface as quickly as possible; for others, it's best to "pin" them in place as long as possible so they can grow and spread. The new analysis, which led to a mathematical system for precisely predicting droplet behavior, can be used to optimize a surface in either way. (Bubbles, such as those on the bottom of a pan of boiling water, behave in essentially the same way).

"People have only been able to make sketches" of how droplet adhesion works, Paxson says. With the new high-resolution imagery, it is now clear that as a droplet peels away from a rough surface, the round droplet forms a series of tiny "necks" adhering to each of the high points on the surface; these necks (which the researchers call "capillary bridges") then gradually stretch, thin and break. The more high spots on the surface, the more of these tiny necks form. "That's where all the adhesion occurs," Paxson says.

The MIT authors say the phenomenon is "self-similar," like fractal structure: Each neck or capillary bridge can consist of several capillary bridges at finer length scales; it is the cumulative effect that dictates the overall adhesion. This self-similarity is exploited by some biological structures for lowering adhesion.

There had been two leading theories on how to calculate the adhesion of droplets: One held that the areas of contact and energy levels of the molecules were key; the other, that the length of the edge of a drop on a surface was critical. The evidence produced by this research strongly supports the second theory. "I think we have now closed a decades-old debate on this one," Varanasi says.

In general, Paxson says, "complicated shapes tend to be more sticky," because of their greater edge-length.

Droplets and bubbles are ubiquitous in many engineering applications. This work could be applied to engineering industrial surfaces with controlled adhesion in applications ranging from large desalination and power plants to consumer products such as fabrics, packaging and medical devices. While some applications, such as condensers, strive to shed droplets quickly from a surface, others — such as ink droplets sprayed onto paper in an inkjet printer — require the reverse. The new methodology might help in improving both functions, the researchers say.

Paxson and Varanasi's formulas can also explain variability among natural textured surfaces — such as lotus leaves, which shed water efficiently, and rose petals, which do not. Finally, the new research could advance our understanding of certain biological processes — such as how water spiders, which make an air bubble to house themselves under the surface of a body of water, control the surface tension to penetrate the bubble.

INFORMATION:

The work was supported by the National Science Foundation and the DuPont-MIT Alliance.

Written by David Chandler, MIT News Office

END

There are "things hidden in plain sight" all around us. But art can help students see their world anew, unlocking discoveries in fields ranging from plant biology to biomedical imaging, according to University of Delaware professor John Jungck.

Jungck's sentiments were echoed by a panel of experts speaking on "Artful Science" on Feb. 15 at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in Boston. Jungck organized the panel and also spoke at the event.

Canoeing on a lake near his home in northwestern Minnesota when he was a youngster, ...

Would you prefer $120 today or $154 in one year? Your answer may depend on how powerful you feel, according to new research in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

Many people tend to forego the larger reward and opt for the $120 now, a phenomenon known as temporal discounting. But research conducted by Priyanka Joshi and Nathanael Fast of the University of Southern California Marshall School of Business suggests that people who feel powerful are more likely to wait for the bigger reward, in part because they feel a stronger connection ...

BOSTON -- Models of the human brain, patterned on engineering control theory, may some day help researchers control such neurological diseases as epilepsy, Parkinson's and migraines, according to a Penn State researcher who is using mathematical models of neuron networks from which more complex brain models emerge.

"The dual concepts of observability and controlability have been considered one of the most important developments in mathematics of the 20th century," said Steven J. Schiff, the Brush Chair Professor of Engineering and director of the Penn State Center for ...

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. – Identifying areas of malarial infection risk depends more on daily temperature variation than on the average monthly temperatures, according to a team of researchers, who believe that their results may also apply to environmentally temperature-dependent organisms other than the malaria parasite.

"Temperature is a key driver of several of the essential mosquito and parasite life history traits that combine to determine transmission intensity, including mosquito development rate, biting rate, development rate and survival of the parasite within the ...

Species facing widespread and rapid environmental changes can sometimes evolve quickly enough to dodge the extinction bullet. Populations of disease-causing bacteria evolve, for example, as doctors flood their "environment," the human body, with antibiotics. Insects, animals and plants can make evolutionary adaptations in response to pesticides, heavy metals and overfishing.

Previous studies have shown that the more gradual the change, the better the chances for "evolutionary rescue" – the process of mutations occurring fast enough to allow a population to avoid extinction ...

Tropical Storm Haruna came together on Feb. 19 in the Southern Indian Ocean and two NASA satellites provided visible and infrared imagery that helped forecasters see the system's organization.

A low pressure area called System 94S developed on Friday, Feb. 15 in the northern Mozambique Channel. Over the course of four days System 94S became more organized and by Feb. 19 it became Tropical Storm Haruna.

On Tuesday, Feb. 19, Tropical Storm Haruna had maximum sustained winds near 35 knots (40.2 mph/64.8 kph). Haruna was located in the Mozambique Channel, near 21.4 south ...

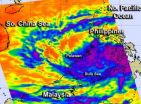

The second tropical depression of the northwestern Pacific Ocean season formed on Feb. 19, and NASA's Aqua satellite showed the storm was soaking the central and southern Philippines.

NASA's Aqua satellite passed over Tropical Depression 02W (TD02W) as it was coming together and soaking provinces in Mindanao and the Palawan province of Luzon. The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument that flies aboard Aqua captured an infrared image of the depression at 0541 UTC (12:41 a.m. EST). The AIRS image showed very cold cloud top temperatures, colder than -63F (-52C) ...

New research out of the University of Cincinnati reveals a relatively rare look into the success of substance abuse treatment programs for African-Americans. Researchers report that self-motivation could be an important consideration into deciding on the most effective treatment strategy. The study led by Ann Kathleen Burlew, a UC professor of psychology, and LaTrice Montgomery, a UC assistant professor of human services, is published online this week in Psychology of Addictive Behaviors.

Specifically among African-Americans, the study investigated the effectiveness of ...

New York, NY (February 19, 2013) — New findings by Columbia researchers suggest that along with amyloid deposits, white matter hyperintensities (WMHs) may be a second necessary factor for the development of Alzheimer's disease.

Most current approaches to Alzheimer's disease focus on the accumulation of amyloid plaque in the brain. The researchers at the Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer's Disease and the Aging Brain, led by Adam M. Brickman, PhD, assistant professor of neuropsychology, examined the additional contribution of small-vessel cerebrovascular disease, ...

Philadelphia, PA, February 20, 2013 – A study published in the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics has determined that there is increasing evidence of a connection between diet and acne, particularly from high glycemic load diets and dairy products, and that medical nutrition therapy (MNT) can play an important role in acne treatment.

More than 17 million Americans suffer from acne, mostly during their adolescent and young adult years. Acne influences quality of life, including social withdrawal, anxiety, and depression, making treatment essential. Since ...