(Press-News.org) Two strains of the type of mosquito responsible for the majority of malaria transmission in Africa have evolved such substantial genetic differences that they are becoming different species, according to researchers behind two new studies published today in the journal Science.

Over 200 million people globally are infected with malaria, according to the World Health Organisation, and the majority of these people are in Africa. Malaria kills one child every 30 seconds.

Today's international research effort, co-led by scientists from Imperial College London, looks at two strains of the Anopheles gambiae mosquito, the type of mosquito primarily responsible for transmitting malaria in sub-Saharan Africa. These strains, known as M and S, are physically identical. However, the new research shows that their genetic differences are such that they appear to be becoming different species, so efforts to control mosquito populations may be effective against one strain of mosquito but not the other.

The scientists argue that when researchers are developing new ways of controlling malarial mosquitoes, for example by creating new insecticides or trying to interfere with their ability to reproduce, they need to make sure that they are effective in both strains.

The authors also suggest that mosquitoes are evolving more quickly than previously thought, meaning that researchers need to continue to monitor the genetic makeup of different strains of mosquitoes very closely, in order to watch for changes that might enable the mosquitoes to evade control measures in the future.

Professor George Christophides, one of the lead researchers behind today's work from the Division of Cell and Molecular Biology at Imperial College London, said: "Malaria is a deadly disease that affects millions of people across the world and amongst children in Africa, it causes one in every five deaths. We know that the best way to reduce the number of people who contract malaria is to control the mosquitoes that carry the disease. Our studies help us to understand the makeup of the mosquitoes that transmit malaria, so that we can find new ways of preventing them from infecting people."

Dr Mara Lawniczak, another lead researcher from the Division of Cell and Molecular Biology at Imperial College London, added: "From our new studies, we can see that mosquitoes are evolving more quickly than we thought and that unfortunately, strategies that might work against one strain of mosquito might not be effective against another. It's important to identify and monitor these hidden genetic changes in mosquitoes if we are to succeed in bringing malaria under control by targeting mosquitoes."

The researchers reached their conclusions after carrying out the most detailed analysis so far of the genomes of the M and S strains of Anopheles gambiae mosquito, over two studies. The first study, which sequenced the genomes of both strains, revealed that M and S are genetically very different and that these genetic differences are scattered around the entire genome. Previous studies had only detected a few 'hot spots' of divergence between the genomes of the two strains. The work suggested that many of the genetic regions that differ between the M and S genomes are likely to affect mosquito development, feeding behaviour, and reproduction.

In the second study, the researchers looked at many individual mosquitoes from the M and S strains, as well as a strain called Bamako, and compared 400,000 different points in their genomes where genetic variations had been identified, to analyse how these mosquitoes are evolving. This showed that the strains appear to be evolving differently, probably in response to factors in their specific environments - for example, different larval habitats or different pathogens and predators. This study was the first to carry out such detailed genetic analysis of an invertebrate, using a high density genotyping array.

As a next step in their research, the Imperial researchers are now carrying out genome-wide association studies of mosquitoes, using the specially designed genotyping chip that they designed for their second study, to explore which variations in mosquito genes affect their propensity to become infected with malaria and other pathogens.

INFORMATION:

Both of the studies published today were collaborations between researchers at Imperial and international colleagues, involving researchers from institutions including the University of Notre Dame, the J. C. Venter Institute, Washington University and the Broad Institute. Funding for the projects was provided by the National Human Genome Research Institute, the National Institutes of Health, the BBSRC, and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

Malarial mosquitoes are evolving into new species, say researchers

2010-10-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

ESHRE publishes new PGD guidelines

2010-10-22

The four guidelines include one outlining the organisation of a PGD centre and three relating to the methods used: amplification-based testing, fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH)-based testing and polar body/embryo biopsy.

"The guidelines are a detailed update to the Consortium's initial PGD guidelines, published in the same journal in 2005. They have been developed as a set which, taken together, form a complete best-practice compendium," said Gary Harton, chairman of ESHRE's PGD Consortium and Head of Molecular Genetics at Reprogenetics in Livingston, New Jersey.

The ...

Forensic scientists use postmortem imaging-guided biopsy to determine natural causes of death

2010-10-22

Researchers found that the combination of computed tomography (CT), postmortem CT angiography (CTA) and biopsy can serve as a minimally invasive option for determining natural causes of death such as cardiac arrest, according to a study in the November issue of the American Journal of Roentgenology (www.ajronline.org).

In the last decade, postmortem imaging, especially CT, has gained increasing acceptance in the forensic field. However, CT has certain limitations in the assessment of natural death.

"Vascular and organ pathologic abnormalities, for example, generally ...

Peripheral induction of Alzheimer's-like brain pathology in mice

2010-10-22

Pathological protein deposits linked to Alzheimer's disease and cerebral amyloid angiopathy can be triggered not only by the administration of pathogenic misfolded protein fragments directly into the brain but also by peripheral administration outside the brain. This is shown in a new study done by researchers at the Hertie Institute of Clinical Brain Research (HIH, University Hospital Tübingen, University of Tübingen) and the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE), to be published in Science on October 21, 2010.

Alzheimer's disease and a brain vascular ...

The sound of the underground! New acoustic early warning system for landslide prediction

2010-10-22

A new type of sound sensor system has been developed to predict the likelihood of a landslide.

Thought to be the first system of its kind in the world, it works by measuring and analysing the acoustic behaviour of soil to establish when a landslide is imminent so preventative action can be taken.

Noise created by movement under the surface builds to a crescendo as the slope becomes unstable and so gauging the increased rate of generated sound enables accurate prediction of a catastrophic soil collapse.

The technique has been developed by researchers at Loughborough ...

Malaria research begins to bite

2010-10-22

Scientists at The University of Nottingham and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute near Cambridge have pin-pointed the 72 molecular switches that control the three key stages in the life cycle of the malaria parasite and have discovered that over a third of these switches can be disrupted in some way.

Their research which has been funded by Wellcome Trust and the Medical Research Council (MRC) is a significant breakthrough in the search for cheap and effective vaccines and drugs to stop the transmission of a disease which kills up to a million children a year.

Until ...

Value-added sulfur scrubbing

2010-10-22

Power plants that burn fossil fuels remain the main source of electricity generation across the globe. Modern power plants have scrubbers to remove sulfur compounds from their flue gases, which has helped reduce the problem of acid rain. Now, researchers in India have devised a way to convert the waste material produced by the scrubbing process into value-added products. They describe details in the International Journal of Environment and Pollution.

Fossil fuels contain sulfur compounds that are released as sulfur dioxide during combustion. As such, flue gas desulfurisation ...

Authoritarian behavior leads to insecure people

2010-10-22

Researchers from the University of Valencia (UV) have identified the effects of the way parents bring up their children on social structure in Spain. Their conclusions show that punishment, deprivation and strict rules impact on a family's self esteem.

"The objective was to analyse which style of parental socialisation is ideal in Spain by measuring the psychosocial adjustment of children", Fernando García, co-author of the study and a researcher at the UV, tells SINC.

The study, which has been published in the latest issue of the journal Infancia y Aprendizaje, was ...

Adverse neighborhood conditions greatly aggravate mobility problems from diabetes

2010-10-22

INDIANAPOLIS – A study published earlier this year in the peer reviewed online journal BMC Public Health has found that residing in a neighborhood with adverse living conditions such as low air quality, loud traffic or industrial noise, or poorly maintained streets, sidewalks and yards, makes mobility problems much more likely in late middle-aged African Americans with diabetes.

"We followed a large group of African Americans for 3 years and found an extremely strong correlation between diabetes and adverse neighborhood conditions. The study participants were between ...

AFM tips from the microwave

2010-10-22

Jena (21 October 2010) Scientists from the Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena (Germany) were successful in improving a fabrication process for Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) probe tips.

Atomic Force Microscopy is able to scan surfaces so that even tiniest nano structures become visible. Knowledge about these structures is for instance important for the development of new materials and carrier systems for active substances. The size of the probe is highly important for the image quality as it limits the dimensions that can be visualized – the smaller the probe, the smaller ...

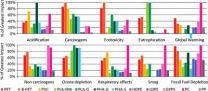

Pitt researchers: Plant-based plastics not necessarily greener than oil-based relatives

2010-10-22

PITTSBURGH—An analysis of plant and petroleum-derived plastics by University of Pittsburgh researchers suggests that biopolymers are not necessarily better for the environment than their petroleum-based relatives, according to a report in Environmental Science & Technology. The Pitt team found that while biopolymers are the more eco-friendly material, traditional plastics can be less environmentally taxing to produce.

Biopolymers trumped the other plastics for biodegradability, low toxicity, and use of renewable resources. Nonetheless, the farming and chemical processing ...