(Press-News.org) DENVER (Feb. 21, 2013) – A new study from the University of Colorado Denver shows that the earliest human burial practices in Eurasia varied widely, with some graves lavish and ornate while the vast majority were fairly plain.

"We don't know why some of these burials were so ornate, but what's striking is that they postdate the arrival of modern humans in Eurasia by almost 10,000 years," said Julien Riel-Salvatore, Ph.D., assistant professor of anthropology at CU Denver and lead author of the study. "When they appear around 30,000 years ago some are lavish but many aren't and over time the most elaborate ones almost disappear. So, the behavior of humans does not always go from simple to complex; it often waxes and wanes in terms of its complexity depending on the conditions people live under."

The study, which examined 85 burials from the Upper Paleolithic period, found that men were buried more often than women. Infants were buried only sporadically, if at all in later periods, a difference that could be related to changes in subsistence, climate and the ability to keep babies alive, Riel-Salvatore said.

It also showed that a few ornate burials in Russia, Italy and the Czech Republic dating back nearly 30,000 years are anomalies, and not representative of most early Homo sapiens burial practices in Eurasia.

"The problem is that these burials are so rare – there's just over three per thousand years for all of Eurasia – that it's difficult to draw clear conclusions about what they meant to their societies," said Riel-Salvatore.

In fact, the majority of the burials were fairly plain and included mostly items of daily life as opposed to ornate burial goods. In that way, many were similar to Neanderthal graves. Both early humans and Neanderthals put bodies into pits sometimes with household items. During the Upper Paleolithic, this included ornaments worn by the deceased while they were alive. When present, ornaments of stone, teeth and shells are often found on the heads and torsos of the dead rather than the lower body, consistent with how they were likely worn in life.

"Some researchers have used burial practices to separate modern humans from Neanderthals," said Riel-Salvatore. "But we are challenging the orthodoxy that all modern human burials were necessarily more sophisticated than those of Neanderthals."

Many scientists believe that the capacity for symbolic behavior separates humans from Neanderthals, who disappeared about 35,000 years ago.

"It's thought to be an expression of abstract thinking" Riel-Salvatore said. "But as research progresses we are finding evidence that Neanderthals engaged in practices generally considered characteristic of modern humans."

Riel-Salvatore is an expert on early modern humans and Neanderthals. His last study proposed that, contrary to popular belief, early humans didn't wipe out Neanderthals but interbred with them, swamping them genetically. Another of his studies demonstrated that Neanderthals in southern Italy adapted, innovated and created technology before contact with modern humans, something previously considered unlikely.

This latest study, "Upper Paleolithic mortuary practices in Eurasia: A critical look at the burial record" co-authored with Claudine Gravel-Miguel (Arizona State University), will be published in The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Death and Burial in April.

It reveals intriguing variation in early human burial customs between 10,000 and 35,000 years ago. And this study raises the question of why there was so much variability in early human burial practices.

"There seems to be little rhyme or reason to it," Riel-Salvatore said. "The main point here is that we need to be careful of using exceptional examples of ornate burials to characterize Upper Paleolithic burial practices as a whole."

INFORMATION:

END

Disruption in the body's circadian rhythm can lead not only to obesity, but can also increase the risk of diabetes and heart disease.

That is the conclusion of the first study to show definitively that insulin activity is controlled by the body's circadian biological clock. The study, which was published on Feb. 21 in the journal Current Biology, helps explain why not only what you eat, but when you eat, matters.

The research was conducted by a team of Vanderbilt scientists directed by Professor of Biological Sciences Carl Johnson and Professors of Molecular Physiology ...

Flower colors that contrast with their background are more important to foraging bees than patterns of colored veins on pale flowers according to new research, by Heather Whitney from the University of Cambridge in the UK, and her colleagues. Their observation of how patterns of pigmentation on flower petals influence bumblebees' behavior suggests that color veins give clues to the location of the nectar. There is little to suggest, however, that bees have an innate preference for striped flowers. The work is published online in Springer's journal, Naturwissenschaften - ...

Scientists from the University of Southampton have identified the molecular system that contributes to the harmful inflammatory reaction in the brain during neurodegenerative diseases.

An important aspect of chronic neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, Huntington's or prion disease, is the generation of an innate inflammatory reaction within the brain.

Results from the study open new avenues for the regulation of the inflammatory reaction and provide new insights into the understanding of the biology of microglial cells, which play a leading ...

A new study shows that children who are exposed to bullying during childhood are at increased risk of psychiatric disorders in adulthood, regardless of whether they are victims or perpetrators.

Professor William E. Copeland of Duke University Medical Center and Professor Dieter Wolke of the University of Warwick led a team in examining whether bullying in childhood predicts psychiatric problems and suicidality in young adulthood. While some still view bullying as a harmless rite of passage, research shows that being a victim of bullying increases the risk of adverse outcomes ...

AUGUSTA, Ga. – Early life stress like that experienced by ill newborns appears to take an early toll of the heart, affecting its ability to relax and refill with oxygen-rich blood, researchers report.

Rat pups separated from their mothers a few hours each day, experienced a significant decrease in this basic heart function when – as life tends to do – an extra stressor was added to raise blood pressure, said Dr. Catalina Bazacliu, neonatologist at the Medical College of Georgia and Children's Hospital of Georgia at Georgia Regents University. Bazacliu worked under the ...

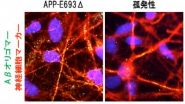

Kyoto, Japan – Working with a group from Nagasaki University, a research group at the Center for iPS Cell Research and Application (CiRA) at Japan's Kyoto University has announced in the Feb. 21 online publication of Cell Stem Cell has successfully modeled Alzheimer's disease (AD) using both familial and sporadic patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and revealed stress phenotypes and differential drug responsiveness associated with intracellular amyloid beta oligomers in AD neurons and astrocytes.

In a study published online in Cell Stem Cell, Associate ...

People who are at greater genetic risk of schizophrenia are more likely to see a fall in IQ as they age, even if they do not develop the condition.

Scientists at the University of

Edinburgh say the findings could lead to new research into how different genes for schizophrenia affect brain function over time. They also show that genes associated with schizophrenia influence people in other important ways besides causing the illness itself.

The researchers used the latest genetic analysis techniques to reach their conclusion on how thinking skills change with age.

They ...

Brussels and Geneva, 20th February 2013 --- Major progress has been made in the past 30 years in the knowledge and management of liver disease, yet approximately 29 million Europeans still suffer from a chronic liver condition.

The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) today unveiled its new publication The burden of liver disease in Europe: a review of available epidemiological data. Key findings in the report suggest that alcohol consumption, viral hepatitis B and C and metabolic syndromes related to overweight and obesity are the leading causes of ...

A lifelong diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids can inhibit growth of breast cancer tumours by 30 per cent, according to new research from the University of Guelph.

The study, published recently in the Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, is believed to be the first to provide unequivocal evidence that omega-3s reduce cancer risk.

"It's a significant finding," said David Ma, a professor in Guelph's Department of Human Health and Nutritional Sciences, and one of the study's authors.

"We show that lifelong exposure to omega-3s has a beneficial role in disease prevention ...

Scientists from the Bonn University Hospital successfully tested a method in mice allowing the morphological and functional sequelae of a myocardial infarction to be reduced. Tiny gas bubbles are made to oscillate within the heart via focused ultrasound - this improves microcirculation and decreases the size of the scar tissue. The results show that the mice, following myocardial infarction, have improved cardiac output as a result of this method, as compared to untreated animals. The study is now being presented in the professional journal PLOS ONE.

Every year in Germany, ...