(Press-News.org) AUGUSTA, Ga. – Early life stress like that experienced by ill newborns appears to take an early toll of the heart, affecting its ability to relax and refill with oxygen-rich blood, researchers report.

Rat pups separated from their mothers a few hours each day, experienced a significant decrease in this basic heart function when – as life tends to do – an extra stressor was added to raise blood pressure, said Dr. Catalina Bazacliu, neonatologist at the Medical College of Georgia and Children's Hospital of Georgia at Georgia Regents University. Bazacliu worked under the mentorship of Dr. Jennifer Pollock, biochemist in the Section of Experimental Medicine in the MCG Department of Medicine.

The relaxation and filling rate remained low in the separation model, although decreases stabilized by ages two and six months, as the rats neared middle age. Both the model and controls experienced decreases in those functions that come naturally with age.

Interestingly, the force with which the heart ejected blood remained unchanged with the additional stressor, angiotensin II, a powerful constrictor of blood vessels. Echocardiography was used to evaluate heart function.

"We expected the heart's ability to relax and refill to lag behind in our model," said Bazacliu, whose research earned her a Young Investigator Award from the Southern Society for Pediatric Research. She is reporting her findings Feb. 22 during the Southern Regional Meetings in New Orleans, sponsored by the society as well as several other groups including the Southern Section of the American Federation for Medical Research.

"We believe these babies may be at increased risk for cardiovascular disease and we are working to understand exactly what puts them at risk," Bazacliu said. She believes hers is the first animal study of this aspect of heart function.

Dr. Analia S. Loria, assistant research scientist in Pollock's lab and also a co-author on the new abstract, has shown that the blood pressure of maternally separated rats goes up more in response to angiotensin II and their heart rates go higher as well. Normally, a compensatory mechanism drives the heart rate down a little when blood pressure goes up.

Work by others has shown persistent blood vessel changes in the early stress model, including increased contraction and reduced relaxation when similarly stressed.

Longitudinal studies in humans have shown long-term cardiovascular implications, such as babies born to mothers during the Dutch famine of World War II, growing up at increased risk for cardiovascular disease as well as diabetes, obesity and other health problems.

Bazacliu's earlier studies in a similar animal model indicated that babies whose growth was restricted in utero by conditions such as preeclampsia – maternal high blood pressure during pregnancy – were at increased risk of cardiovascular disease as adults. This was true whether the babies were born prematurely or at full term. Increased pressure during development reduces blood flow from mother to baby; reduced nutrition and oxygen to the baby is considered an environmental stress.

Bazacliu's interest in early life stress grew out of the reality that, while obviously intended to save premature and otherwise critically ill newborns, neonatal intensive care units can further stress these babies. "All the procedures we must do, the separation from the mother, the environment, even though the babies need the help, it represents a stress." NICUs such as the one at Children's Hospital of Georgia work to minimize negative impact with strategies such as open visiting hours, minimalizing noise and other family-centered care strategies.

Bazacliu came to MCG in 2011 from the University of Buffalo School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences.

INFORMATION:

Early life stress may take early toll on heart function

2013-02-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

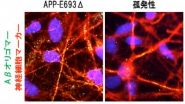

Modeling Alzheimer's disease using iPSCs

2013-02-21

Kyoto, Japan – Working with a group from Nagasaki University, a research group at the Center for iPS Cell Research and Application (CiRA) at Japan's Kyoto University has announced in the Feb. 21 online publication of Cell Stem Cell has successfully modeled Alzheimer's disease (AD) using both familial and sporadic patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and revealed stress phenotypes and differential drug responsiveness associated with intracellular amyloid beta oligomers in AD neurons and astrocytes.

In a study published online in Cell Stem Cell, Associate ...

Schizophrenia genes increase chance of IQ loss

2013-02-21

People who are at greater genetic risk of schizophrenia are more likely to see a fall in IQ as they age, even if they do not develop the condition.

Scientists at the University of

Edinburgh say the findings could lead to new research into how different genes for schizophrenia affect brain function over time. They also show that genes associated with schizophrenia influence people in other important ways besides causing the illness itself.

The researchers used the latest genetic analysis techniques to reach their conclusion on how thinking skills change with age.

They ...

EASL publishes first comprehensive literature review on the burden of liver disease in Europe

2013-02-21

Brussels and Geneva, 20th February 2013 --- Major progress has been made in the past 30 years in the knowledge and management of liver disease, yet approximately 29 million Europeans still suffer from a chronic liver condition.

The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) today unveiled its new publication The burden of liver disease in Europe: a review of available epidemiological data. Key findings in the report suggest that alcohol consumption, viral hepatitis B and C and metabolic syndromes related to overweight and obesity are the leading causes of ...

Omega-3s inhibit breast cancer tumor growth, study finds

2013-02-21

A lifelong diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids can inhibit growth of breast cancer tumours by 30 per cent, according to new research from the University of Guelph.

The study, published recently in the Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, is believed to be the first to provide unequivocal evidence that omega-3s reduce cancer risk.

"It's a significant finding," said David Ma, a professor in Guelph's Department of Human Health and Nutritional Sciences, and one of the study's authors.

"We show that lifelong exposure to omega-3s has a beneficial role in disease prevention ...

Microbubbles improve myocardial remodelling after infarction

2013-02-21

Scientists from the Bonn University Hospital successfully tested a method in mice allowing the morphological and functional sequelae of a myocardial infarction to be reduced. Tiny gas bubbles are made to oscillate within the heart via focused ultrasound - this improves microcirculation and decreases the size of the scar tissue. The results show that the mice, following myocardial infarction, have improved cardiac output as a result of this method, as compared to untreated animals. The study is now being presented in the professional journal PLOS ONE.

Every year in Germany, ...

Inhaled betadine leads to rare complication

2013-02-21

Philadelphia, Pa. (February 21, 2013) - A routine step in preparing for cleft palate surgery in a child led to an unusual—but not unprecedented—case of lung inflammation (pneumonitis), according to a report in the The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. The journal, edited by Mutaz B. Habal, MD, FRCSC, is published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a part of Wolters Kluwer Health.

The complication resulted from accidental inhalation of povidone-iodine (PI), or Betadine—an antiseptic widely used before surgery. The rare complication led to new surgical "prep" steps to reduce ...

Human heart development slower than other mammals

2013-02-21

The walls of the human heart are a disorganised jumble of tissue until relatively late in pregnancy, despite having the shape of a fully functioning heart, according to a pioneering study.

Experts from the University of Sheffield's Medical School collaborated on research to create the first comprehensive model of human heart development using observations of living foetal hearts. The results showed surprising differences from existing animal models.

Although scientists saw four clearly defined chambers in the foetal heart from the eighth week of pregnancy, they did ...

The age from when children can hop on one leg

2013-02-21

This press release is available in German. Motor development in children under five years of age can now be tested reliably: Together with colleagues from Lausanne, researchers from the University Children's Hospital Zurich and the University of Zurich have determined normative data for different exercises such as hopping or running. This enables parents and experts to gage the motor skills of young children for the first time objectively and thus identify abnormalities at an early stage.

My child still can't stand on one leg or walk down the stairs in alternating ...

Scientists unveil secrets of important natural antibiotic

2013-02-21

An international team of scientists has discovered how an important natural antibiotic called dermcidin, produced by our skin when we sweat, is a highly efficient tool to fight tuberculosis germs and other dangerous bugs.

Their results could contribute to the development of new antibiotics that control multi-resistant bacteria.

Scientists have uncovered the atomic structure of the compound, enabling them to pinpoint for the first time what makes dermcidin such an efficient weapon in the battle against dangerous bugs.

Although about 1700 types of these natural antibiotics ...

In rich and poor nations, giving makes people feel better than getting, research finds

2013-02-21

WASHINGTON - Feeling good about spending money on someone else rather than for personal benefit may be a universal response among people in both impoverished countries and rich nations, according to new research published by the American Psychological Association.

"Our findings suggest that the psychological reward experienced from helping others may be deeply ingrained in human nature, emerging in diverse cultural and economic contexts," said lead author Lara Aknin, PhD, of Simon Fraser University in Canada.

The findings provide the first empirical evidence that "the ...