(Press-News.org) The walls of the human heart are a disorganised jumble of tissue until relatively late in pregnancy, despite having the shape of a fully functioning heart, according to a pioneering study.

Experts from the University of Sheffield's Medical School collaborated on research to create the first comprehensive model of human heart development using observations of living foetal hearts. The results showed surprising differences from existing animal models.

Although scientists saw four clearly defined chambers in the foetal heart from the eighth week of pregnancy, they did not find organised muscle tissue until the 20th week -much later than expected.

Developing an accurate, computerised simulation of the foetal heart is critical to understanding normal heart development in the womb and, eventually, to opening new ways of detecting and dealing with some functional abnormalities early in pregnancy.

Studies of early heart development have previously been largely based on other mammals such as mice or pigs, adult hearts and dead human samples. The research team, led by scientists at the University of Leeds is using scans of healthy foetuses in the womb, including one mother who volunteered to have detailed weekly ECG (electrocardiography) scans from 18 weeks until just before delivery.

This functional data is incorporated into a 3D computerised model built up using information about the structure, shape and size of the different components of the heart from two types of MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) scans of foetuses' hearts.

Martyn Paley, Professor of BioMedical Imaging at the University of Sheffield's Department of Cardiovascular Science, said: "We used our extensive expertise in Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) physics and engineering to optimise the acquisition of very high spatial resolution isotropic 3D images of the foetal heart at later gestational ages using rapid FLASH sequences.

"This allowed the morphology of the foetal heart to be studied with unprecedented detail in collaboration with the University of Leeds and the other centres."

Early results are already suggesting that the human heart may develop on a different timeline from other mammals.

While the tissue in the walls of a pig heart develops a highly organised structure at a relatively early stage of a foetus's development, a paper published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface Focus reports that the there is little organisation of the human heart's cells until 20 weeks into pregnancy.

A pig's pregnancy lasts about three months and the organised structure of the walls of the heart emerge in the first month of pregnancy. The new study only detected similar organised structures well into the second trimester of the human pregnancy. Human foetuses have a regular heartbeat from about 22 days.

Dr Eleftheria Pervolaraki, Visiting Research Fellow at the University of Leeds' School

of Biomedical Sciences, said: "For a heart to be beating effectively, we thought you needed a smoothly changing orientation of the muscle cells through the walls of the heart chambers. Such an organisation is seen in the hearts of all healthy adult mammals.

"Foetal hearts in other mammals such as pigs, which we have been using as models, show such an organisation even early in gestation, with a smooth change in cell orientation going through the heart wall. But what we actually found is that such organisation was not detectable in the human foetus before 20 weeks," she said.

Professor Arun Holden, also from Leeds' School of Biomedical Sciences, added: "The development of the foetal human heart is on a totally different timeline, a slower timeline, from the model that was being used before.

"This upsets our assumptions and raises new questions. Since the wall of the heart is structurally disorganised, we might expect to find arrhythmias, which are a bad sign in an adult.

"It may well be that in the early stages of development of the heart arrhythmias are not necessarily pathological and that there is no need to panic if we find them. Alternatively, we could find that the disorganisation in the tissue does not actually lead to arrhythmia."

###

The research was conducted by a team including academics from the University of Sheffield, University of Leeds, the University of Edinburgh, the University of Nottingham, and the University of Manchester.

Notes for Editors

The University of Sheffield

With nearly 25,000 of the brightest students from 125 countries come to the University of Sheffield to learn alongside 1,181 of the world's best academics at one of the UK's leading universities. Staff and students at Sheffield are committed to helping discover and understand the causes of things - and propose solutions that have the power to transform the world we live in.

A member of the Russell Group, the University of Sheffield has a reputation for world-class teaching and research excellence across a wide range of disciplines. The University of Sheffield has been named University of the Year in the Times Higher Education Awards 2011 for its exceptional performance in research, teaching, access and business performance. In addition, the University has won four Queen's Anniversary Prizes (1998, 2000, 2002, 2007), recognising the outstanding contribution by universities and colleges to the United Kingdom's intellectual, economic, cultural and social life.

One of the markers of a leading university is the quality of its alumni and Sheffield boasts five Nobel Prize winners among former staff and students. Its alumni have gone on to hold positions of great responsibility and influence all over the world, making significant contributions in their chosen fields.

Research partners and clients include Boeing, Rolls-Royce, Unilever, Boots, AstraZeneca, GSK, ICI, Slazenger, and many more household names, as well as UK and overseas government agencies and charitable foundations.

The University has well-established partnerships with a number of universities and major corporations, both in the UK and abroad. Its partnership with Leeds and York Universities in the White Rose Consortium has a combined research power greater than that of either Oxford or Cambridge.

For further information, please visit www.sheffield.ac.uk

For further information please contact: Amy Pullan, Media Relations Officer, on 0114 222 9859 or email a.l.pullan@sheffield.ac.uk

To view this news release and images online, visit: http://www.shef.ac.uk/news/nr/human-heart-development-slower-than-other-mammals-1.255355

To read other news releases about the University of Sheffield, visit: http://www.shef.ac.uk/news END

Human heart development slower than other mammals

2013-02-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

The age from when children can hop on one leg

2013-02-21

This press release is available in German. Motor development in children under five years of age can now be tested reliably: Together with colleagues from Lausanne, researchers from the University Children's Hospital Zurich and the University of Zurich have determined normative data for different exercises such as hopping or running. This enables parents and experts to gage the motor skills of young children for the first time objectively and thus identify abnormalities at an early stage.

My child still can't stand on one leg or walk down the stairs in alternating ...

Scientists unveil secrets of important natural antibiotic

2013-02-21

An international team of scientists has discovered how an important natural antibiotic called dermcidin, produced by our skin when we sweat, is a highly efficient tool to fight tuberculosis germs and other dangerous bugs.

Their results could contribute to the development of new antibiotics that control multi-resistant bacteria.

Scientists have uncovered the atomic structure of the compound, enabling them to pinpoint for the first time what makes dermcidin such an efficient weapon in the battle against dangerous bugs.

Although about 1700 types of these natural antibiotics ...

In rich and poor nations, giving makes people feel better than getting, research finds

2013-02-21

WASHINGTON - Feeling good about spending money on someone else rather than for personal benefit may be a universal response among people in both impoverished countries and rich nations, according to new research published by the American Psychological Association.

"Our findings suggest that the psychological reward experienced from helping others may be deeply ingrained in human nature, emerging in diverse cultural and economic contexts," said lead author Lara Aknin, PhD, of Simon Fraser University in Canada.

The findings provide the first empirical evidence that "the ...

Cell therapy a little more concrete thanks to VIB research

2013-02-21

Cell therapy is a promising alternative to tissue and organ transplantation for diseases that are caused by death or poor functioning of cells. Considering the ethical discussions surrounding human embryonic stem cells, a lot is expected of the so-called 'induced pluripotent stem cells' (iPS cells). However, before this technique can be applied effectively, a lot of research is required into the safety and efficacy of such iPS cells. VIB scientists associated to the UGent have developed a mouse model that can advance this research to the next step.

Lieven Haenebalcke ...

VHA plays leading role in health information technology implementation and research

2013-02-21

Philadelphia, Pa. (February 21, 2013) - The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is aiming to become a leader in using health information technology (HIT) to change the way patients experience medical care, to decrease medical mistakes, and to improve health outcomes. A special March supplement of Medical Care highlights new research into the many and varied types of HIT projects being explored to improve the quality of patient care throughout the VHA system. Medical Care is published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a part of Wolters Kluwer Health.

The special issue ...

Antibacterial protein's molecular workings revealed

2013-02-21

On the front lines of our defenses against bacteria is the protein calprotectin, which "starves" invading pathogens of metal nutrients.

Vanderbilt investigators now report new insights to the workings of calprotectin – including a detailed structural view of how it binds the metal manganese. Their findings, published online before print in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, could guide efforts to develop novel antibacterials that limit a microbe's access to metals.

The increasing resistance of bacteria to existing antibiotics poses a severe threat to ...

When water speaks

2013-02-21

Why certain catalyst materials work more efficiently when they are surrounded by water instead of a gas phase is unclear. RUB chemists have now gleamed some initial answers from computer simulations. They showed that water stabilises specific charge states on the catalyst surface. "The catalyst and the water sort of speak with each other" says Professor Dominik Marx, depicting the underlying complex charge transfer processes. His research group from the Centre for Theoretical Chemistry also calculated how to increase the efficiency of catalytic systems without water by ...

Sniffing out the side effects of radiotherapy may soon be possible

2013-02-21

Researchers at the University of Warwick and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust have completed a study that may lead to clinicians being able to more accurately predict which patients will suffer from the side effects of radiotherapy.

Gastrointestinal side effects are commonplace in radiotherapy patients and occasionally severe, yet there is no existing means of predicting which patients will suffer from them. The results of the pilot study, published in the journal Sensors, outline how the use of an electronic nose and a newer technology, FAIMS (Field Asymmetric ...

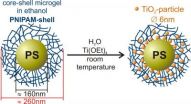

Titanium dioxide nanoreactor

2013-02-21

This press release is available in German.

Now, Dr. Katja Henzler and a team of chemists at the Helmholtz Centre Berlin have developed a synthesis to produce nanoparticles at room temperature in a polymer network. Their analysis, conducted at BESSY II, Berlin's synchrotron radiation source, has revealed the crystalline structure of the nanoparticles. This represents a major step forward in the usage of polymeric nanoreactors since, until recently, the nanoparticles had to be thoroughly heated to get them to crystallize. The last synthesis step can be spared due ...

Wanted: A life outside the workplace

2013-02-21

EAST LANSING, Mich. — A memo to employers: Just because your workers live alone doesn't mean they don't have lives beyond the office.

New research at Michigan State University suggests the growing number of workers who are single and without children have trouble finding the time or energy to participate in non-work interests, just like those with spouses and kids.

Workers struggling with work-life balance reported less satisfaction with their lives and jobs and more signs of anxiety and depression.

"People in the study repeatedly said I can take care of my job demands, ...