Antibacterial protein's molecular workings revealed

2013-02-21

(Press-News.org) On the front lines of our defenses against bacteria is the protein calprotectin, which "starves" invading pathogens of metal nutrients.

Vanderbilt investigators now report new insights to the workings of calprotectin – including a detailed structural view of how it binds the metal manganese. Their findings, published online before print in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, could guide efforts to develop novel antibacterials that limit a microbe's access to metals.

The increasing resistance of bacteria to existing antibiotics poses a severe threat to public health, and new therapeutic strategies to fight these pathogens are needed.

The idea of "starving" bacteria of metal nutrients is appealing, said Eric Skaar, Ph.D., MPH, associate professor of Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology. In a series of previous studies, Skaar, Walter Chazin, Ph.D., and Richard Caprioli, Ph.D., demonstrated that calprotectin is highly expressed by host immune cells at sites of infection. They showed that calprotectin inhibits bacterial growth by "mopping up" the manganese and zinc that bacteria need for replication.

Now, the researchers have identified the structural features of calprotectin's two metal binding sites and demonstrated that manganese binding is key to its antibacterial action.

Calprotectin is a member of the family of S100 calcium-binding proteins, which Chazin, professor of Biochemistry and Chemistry, has studied for many years. Chazin and postdoctoral fellow Steven Damo, Ph.D., used existing structural data from other S100 family members to zero in on calprotectin's two metal binding sites. Then, they selectively mutated one site or the other.

They discovered that calprotectin with mutations in one of the two sites still bound both zinc and manganese, but calprotectin with mutations in the other site only bound zinc. The researchers recognized that these modified calprotectins – especially the one that could no longer bind manganese – would be useful tools for determining the importance of manganese binding to calprotectin's functions, Chazin noted.

Thomas Kehl-Fie, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in Skaar's group, used these altered calprotectins to demonstrate that the protein's ability to bind manganese is required for full inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus growth. The investigators also showed that Staph bacteria require manganese for a certain process the bacteria use to protect themselves from reactive oxygen species.

"These altered calprotectin proteins were key to being able to tease apart the importance of the individual metals – zinc and manganese – to the bacterium as a whole and to metal-dependent processes within the bacteria," Skaar said. "They're really powerful tools."

Skaar explained that calprotectin likely binds two different metals to increase the range of bacteria that it inhibits. The investigators tested the modified calprotectins against a panel of medically important bacterial pathogens.

"Bacteria have different metal needs," Skaar said. "Some bacteria are more sensitive to the zinc-binding properties of calprotectin, and others are more sensitive to the manganese-binding properties."

To fully understand how calprotectin binds manganese, Damo and Chazin – with assistance from Günter Fritz, Ph.D., at the University of Freiburg in Germany – produced calprotectin crystals with manganese bound and determined the protein structure. They found that manganese slips into a position where it interacts with six histidine amino acids of calprotectin.

"It's really beautiful; no one's ever seen a protein chelate (bind) manganese like this," Chazin said.

The structure explains why calprotectin is the only S100 family member that binds manganese and has the strongest antimicrobial action, and it may allow researchers to design a calprotectin that only binds manganese (not zinc). Such a tool would be useful for studying why bacteria require manganese – and then targeting those microbial processes in new therapeutic strategies, Chazin and Skaar noted.

"We do not know all of the processes within Staph that require manganese; we just know if they don't have it, they die," Skaar said. "If we can discover the proteins in Staph that require manganese – the things that are required for growth – then we can target those proteins."

The team recently was awarded a five-year, $2 million grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI101171) to advance their studies of calprotectin and how it works to limit bacterial infections and in other inflammatory conditions.

"Nature stumbled onto an interesting antimicrobial strategy," Chazin said. "Our goal is to really tease apart the importance of metal binding to all of calprotectin's different roles – and to take advantage of our findings to design new antibacterial agents."

###

The research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA009582, HL094296, AI091771, AI069233, AI073843, GM062122). Skaar holds the Ernest W. Goodpasture Chair in Pathology; Chazin holds the Chancellor's Chair in Biochemistry and Chemistry and is director of the Vanderbilt Center for Structural Biology. END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

When water speaks

2013-02-21

Why certain catalyst materials work more efficiently when they are surrounded by water instead of a gas phase is unclear. RUB chemists have now gleamed some initial answers from computer simulations. They showed that water stabilises specific charge states on the catalyst surface. "The catalyst and the water sort of speak with each other" says Professor Dominik Marx, depicting the underlying complex charge transfer processes. His research group from the Centre for Theoretical Chemistry also calculated how to increase the efficiency of catalytic systems without water by ...

Sniffing out the side effects of radiotherapy may soon be possible

2013-02-21

Researchers at the University of Warwick and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust have completed a study that may lead to clinicians being able to more accurately predict which patients will suffer from the side effects of radiotherapy.

Gastrointestinal side effects are commonplace in radiotherapy patients and occasionally severe, yet there is no existing means of predicting which patients will suffer from them. The results of the pilot study, published in the journal Sensors, outline how the use of an electronic nose and a newer technology, FAIMS (Field Asymmetric ...

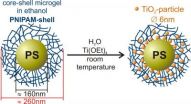

Titanium dioxide nanoreactor

2013-02-21

This press release is available in German.

Now, Dr. Katja Henzler and a team of chemists at the Helmholtz Centre Berlin have developed a synthesis to produce nanoparticles at room temperature in a polymer network. Their analysis, conducted at BESSY II, Berlin's synchrotron radiation source, has revealed the crystalline structure of the nanoparticles. This represents a major step forward in the usage of polymeric nanoreactors since, until recently, the nanoparticles had to be thoroughly heated to get them to crystallize. The last synthesis step can be spared due ...

Wanted: A life outside the workplace

2013-02-21

EAST LANSING, Mich. — A memo to employers: Just because your workers live alone doesn't mean they don't have lives beyond the office.

New research at Michigan State University suggests the growing number of workers who are single and without children have trouble finding the time or energy to participate in non-work interests, just like those with spouses and kids.

Workers struggling with work-life balance reported less satisfaction with their lives and jobs and more signs of anxiety and depression.

"People in the study repeatedly said I can take care of my job demands, ...

Research discovers gene mutation causing rare eye disease

2013-02-21

New Orleans, LA – Research conducted by Dr. Jayne S. Weiss, Professor and Chair of Ophthalmology at LSU Health Sciences Center New Orleans, and colleagues has discovered a new mutation in a gene that causes Schnyder corneal dystrophy (SCD.) The gene was found to be involved in vitamin K metabolism suggesting the possibility that vitamin K may eventually be found useful in its treatment. The findings are published in the February 2013 issue of the peer-reviewed journal, Human Mutation.

Schnyder corneal dystrophy is a rare hereditary eye disease that results in progressive ...

City layout key to predicting riots

2013-02-21

In the future police will be able to predict the spread of riots, and how they impact on cities, thanks to a new computer model.

Developed by researchers at UCL, the model highlights the importance of considering the layout of cities in order for police to suppress disorder as quickly as possible once a riot is in progress.

"As riots are rare events it is difficult to anticipate if and how they will evolve. Consequently, one of the main strategic issues that arose for the police during the 2011 London riots concerned when and where to deploy resources and how many ...

Rutgers neuroscientist sheds light on cause for 'chemo brain'

2013-02-21

It's not unusual for cancer patients being treated with chemotherapy to complain about not being able to think clearly, connect thoughts or concentrate on daily tasks. The complaint – often referred to as chemo-brain – is common. The scientific cause, however, has been difficult to pinpoint.

New research by Rutgers University behavioral neuroscientist Tracey Shors offers clues for this fog-like condition, medically known as chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment. In a featured article published in the European Journal of Neuroscience, Shors and her colleagues argue ...

Mercury may have harbored an ancient magma ocean

2013-02-21

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- By analyzing Mercury's rocky surface, scientists have been able to partially reconstruct the planet's history over billions of years. Now, drawing upon the chemical composition of rock features on the planet's surface, scientists at MIT have proposed that Mercury may have harbored a large, roiling ocean of magma very early in its history, shortly after its formation about 4.5 billion years ago.

The scientists analyzed data gathered by MESSENGER (MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging), a NASA probe that has orbited the planet since ...

Discovering the birth of an asteroid trail

2013-02-21

Unlike comets, asteroids are not characterised by exhibiting a trail, but there are now ten exceptions. Spanish researchers have observed one of these rare asteroids from the Gran Telescopio Canarias (Spain) and have discovered that something happened around the 1st July 2011 causing its trail to appear: maybe internal rupture or collision with another asteroid.

Ten asteroids have been located to date that at least at one moment have displayed a trail like that of comets. They are named main-belt comets (MBC) as they have a typical asteroidal orbit but display a trail ...

Activation of cortical type 2 cannabinoid receptors ameliorates ischemic brain injury

2013-02-21

Philadelphia, PA, February 21, 2013 – A new study published in the March issue of The American Journal of Pathology suggests that cortical type 2 cannabinoid (CB2) receptors might serve as potential therapeutic targets for cerebral ischemia.

Researchers found that the cannabinoid trans-caryophyllene (TC) protected brain cells from the effects of ischemia in both in vivo and in vitro animal models. In rats, post-ischemic treatment with TC decreased cerebral infarct size and edema. In cell cultures composed of rat cortical neurons and glia exposed to oxygen-glucose deprivation ...