(Press-News.org) Dining on field grasses would be ruinous to human teeth, but mammals such as horses, rhinos and gazelles evolved long, strong teeth that are up to the task.

New research led by the University of Washington challenges the 140-year-old assumption that finding fossilized remains of prehistoric animals with such teeth meant the animals were living in grasslands and savannas. Instead it appears certain South American mammals evolved the teeth in response to the gritty dust and volcanic ash they encountered while feeding in an ancient tropical forest.

The new work was conducted in Argentina where scientists had thought Earth's first grasslands emerged 38 million years ago, an assumption based on fossils of these specialized teeth. But the grasslands didn't exist. Instead there were tropical forests rich with palms, bamboos and gingers, according to Caroline Strömberg, UW assistant professor of biology and lead author of an article in Nature Communications.

"The assumption about grasslands and the evolution of these teeth was based on animal fossils," Strömberg said. "No one had looked in detail at evidence from the plant record before. Our findings show that you shouldn't assume adaptations always came about in the same way, that the trigger is the same environment every time."

To handle a lifetime of rough abrasion, the specialized teeth – called high-crowned cheek teeth – are especially long and mostly up in the animals' gums when they are young. As chewing surfaces of the teeth wear away, more of the tooth emerges from the gums until the crowns are used up. In each tooth, bone-like dentin and tough enamel are complexly folded and layered to create strong ridged surfaces for chewing. Human teeth have short crowns and enamel only on the outside of each tooth.

In Argentina, mammals apparently developed specialized teeth 20 million years or more before grasslands appeared, Strömberg said. This was different from her previous work in North America and western Eurasia where she found the emergence of grasslands coincided with the early ancestors of horses and other animals evolving specialized teeth. The cause and effect, however, took 4 million years, considerably more lag time than previously thought.

The idea that specialized teeth could have evolved in response to eating dust and grit on plants and the ground is not new. In the case of Argentine mammals, Strömberg and her co-authors hypothesize that the teeth adapted to handle volcanic ash because so much is present at the study site. For example, some layers of volcanic ash are as thick as 20 feet (six meters). In other layers, soils and roots were just starting to develop when they were smothered with more ash.

Chewing grasses is abrasive because grasses take up more silica from soils than most other plants. Silica forms minute particles inside many plants called phytoliths that, among other things, help some plants stand upright and form part of the protective coating on seeds.

Phytoliths vary in appearance under a microscope depending on the kind of plant. When plants die and decay, the phytoliths remain as part of the soil layer. In work funded by the National Science Foundation, Strömberg and her colleagues collected samples from Argentina's Gran Barranca, literally "Great Cliff," that offers access to layers of soil, ash and sand going back millions of years.

The phytoliths they found in 38-million-year-old layers – when ancient mammals in that part of the world developed specialized teeth – were overwhelmingly from tropical forests, Strömberg said.

"In modern grasslands and savannas you'd expect at least 35 to 40 percent – more likely well over 50 percent – of grass phytoliths. The fact we have so little evidence of grasses is very diagnostic of a forested habitat," she said.

The emergence of grasslands and the evolution of specialized teeth in mammals are regarded as a classic example of co-evolution, one that has occurred in various places around the world. However, as the new work shows, "caution is required when using this functional trait for habitat reconstruction," the co-authors write.

INFORMATION:

Other co-authors are Regan Dunn, a UW doctoral candidate; Richard Madden, University of Chicago; Matthew Kohn, Boise State University; and Alfredo Carlini, National University of La Plata, Argentina.

For more information:

Strömberg is on parental leave, email her at caestrom@uw.edu to arrange interviews

Images available at:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/uwnews/sets/72157632892288230/

Suggested websites:

Nature Communications

http://www.nature.com/ncomms/index.html

Nature Communications article "Decoupling the spread of grasslands from the evolution of grazer-type herbivores in South America"

http://www.nature.com/ncomms/journal/v4/n2/full/ncomms2508.html

Caroline Strömberg

http://www.biology.washington.edu/users/caroline-stromberg

Regan Dunn

http://www.biology.washington.edu/users/regan-dunn

Richard Madden

http://evolutionaryanthropology.duke.edu/people?subpage=profile&Gurl=/aas/BAA&Uil=rick_madden

Matthew Kohn

http://earth.boisestate.edu/mattkohn/

'True grit' erodes assumptions about evolution

2013-03-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

MIT researchers develop solar-to-fuel roadmap for crystalline silicon

2013-03-05

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Bringing the concept of an "artificial leaf" closer to reality, a team of researchers at MIT has published a detailed analysis of all the factors that could limit the efficiency of such a system. The new analysis lays out a roadmap for a research program to improve the efficiency of these systems, and could quickly lead to the production of a practical, inexpensive and commercially viable prototype.

Such a system would use sunlight to produce a storable fuel, such as hydrogen, instead of electricity for immediate use. This fuel could then be used on demand ...

Lawrence Livermore helps find link to arsenic-contaminated groundwater

2013-03-05

Human activities are not the primary cause of arsenic found in groundwater in Bangladesh.

Instead, a team of researchers from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Barnard College, Columbia University, University of Dhaka, Desert Research Institute and University of Tennessee found that the arsenic in groundwater in the region is part of a natural process that predates any recent human interaction, such as intensive pumping.

The results appear in the March 4 edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Millions of people in Bangladesh and neighboring ...

BUSM researchers use goal-oriented therapy to treat diabetic neuropathies

2013-03-05

(Boston) – Researchers at Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) and VA Boston Healthcare System (VA BHS) have found that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can help relieve pain for people with painful diabetic neuropathies. The study, which is the first of its kind to examine this treatment for people with type II diabetes mellitus, is published in the March issue of the Journal of Pain.

Type II diabetes mellitus is the most common form of the disease and affects more than 20 million Americans. The onset of type II diabetes mellitus is often gradual, occurring ...

How the brain loses and regains consciousness

2013-03-05

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Since the mid-1800s, doctors have used drugs to induce general anesthesia in patients undergoing surgery. Despite their widespread use, little is known about how these drugs create such a profound loss of consciousness.

In a new study that tracked brain activity in human volunteers over a two-hour period as they lost and regained consciousness, researchers from MIT and Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) have identified distinctive brain patterns associated with different stages of general anesthesia. The findings shed light on how one commonly used ...

NASA Goddard lab works at extreme edge of cosmic ice

2013-03-05

VIDEO:

NASA scientists at the Goddard Cosmic Ice Lab are studying a kind of chemistry almost never found on Earth. The extreme cold, hard vacuum, and high radiation environment of space...

Click here for more information.

Behind locked doors, in a lab built like a bomb shelter, Perry Gerakines makes something ordinary yet truly alien: ice. This isn't the ice of snowflakes or ice cubes. No, this ice needs such intense cold and low pressure to form that the right conditions ...

Sometimes, the rubber meets the road when you don't want it to

2013-03-05

Back in 2010, the ideas behind a squid's sticky tendrils and Spiderman's super-strong webbing were combined to create a prototype for the first remote device able to stop vehicles in their tracks: the Safe, Quick, Undercarriage Immobilization Device (SQUID). At the push of a button, spiked arms shot out and entangled in a car's axles—bringing a racing vehicle to a screeching halt.*

The need to stop vehicles remotely was identified by the law enforcement community. With funding from Homeland Security's Science & Technology Directorate, and the expertise of the engineers ...

Colon cancer screening doubles with new e-health record use

2013-03-05

SEATTLE—Researchers used electronic health records to identify Group Health patients who weren't screened regularly for cancer of the colon and rectum—and to encourage them to be screened. This centralized, automated approach doubled these patients' rates of on-time screening—and saved health costs—over two years. The March 5 Annals of Internal Medicine published the randomized controlled trial.

"Screening for colorectal cancer can save lives, by finding cancer early—and even by detecting polyps before cancer starts," said study leader Beverly B. Green, MD, MPH. "But ...

Study uncovers enzyme's double life, critical role in cancer blood supply

2013-03-05

Studied for decades for their essential role in making proteins within cells, several amino acids known as tRNA synthetases were recently found to have an unexpected – and critical – additional role in cancer metastasis in a study conducted collaboratively in the labs of Karen Lounsbury, Ph.D., University of Vermont professor of pharmacology, and Christopher Francklyn, Ph.D., UVM professor of biochemistry. The group determined that threonyl tRNA synthetase (TARS) leads a "double life," functioning as a critical factor regulating a pathway used by invasive cancers to induce ...

Fishers near marine protected areas go farther for catch but fare well

2013-03-05

VANCOUVER, Wash.—Fishers near marine protected areas end up traveling farther to catch fish but maintain their social and economic well-being, according to a study by fisheries scientists at Washington State University and in Hawaii.

The study, reported in the journal Biological Conservation, is one of the first to look closely at how protected areas in small nearshore fisheries can affect where fishers operate on the ocean and, as a consequence, their livelihood.

"Where MPAs are located in relation to how fishers operate on the seascape is critical to understand for ...

'Mean girls' be warned: Ostracism cuts both ways

2013-03-05

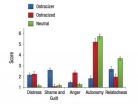

If you think giving someone the cold shoulder inflicts pain only on them, beware. A new study shows that individuals who deliberately shun another person are equally distressed by the experience.

"In real life and in academic studies, we tend to focus on the harm done to victims in cases of social aggression," says co-author Richard Ryan, professor of clinical and social psychology at the University of Rochester. "This study shows that when people bend to pressure to exclude others, they also pay a steep personal cost. Their distress is different from the person excluded, ...