(Press-News.org) In recent years, a body of publications in the microbiology field has challenged all previous knowledge of how antibiotics kill bacteria. "A slew of papers came out studying this phenomenon, suggesting that there is a general mechanism of killing by antibiotics," said Kim Lewis, Northeastern University Distinguished Professor in the Department of Biology and director of Northeastern's Antimicrobial Discovery Center.

The standard thinking at the time was that the three main classes of bactericidal antibiotics each had a unique way of killing bacterial cells—like specialized assassins each trained in a single type of weaponry. But this new research suggested that all antibiotics work the same way, by urging bacterial cells to make compounds called reactive oxygen species, or ROS, which bacteria are naturally susceptible to.

"If they were right it would have been an important finding that could have changed the way we treat patients," said Iris Keren, a senior scientist in Lewis' lab.

And that's exactly how science usually works, said Lewis—through challenges to mainstream thinking. But recent results reported by Lewis, Keren, and their research partners in an article published Friday in the journal Science suggest that this alternative hypothesis doesn't hold up. For example, even bacteria that are incapable of making ROS are still vulnerable to antibiotics. Further, some antibiotics can work their fatal magic in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions—but reactive oxygen species can only form when there's oxygen to fuel them.

"We chose to do the simplest and most critical experiment aimed at falsifying this hypothesis," said Lewis. "Killing by antibiotics is unrelated to ROS production," the authors wrote. The findings were corroborated by University of Illinois researchers in another study released on Friday.

The team treated bacterial cultures with antibiotics in both the presence and absence of oxygen. Other than the gaseous environment, the two treatments were identical. There was no difference in cell death between the two populations.

Before performing these experiments, Lewis' team first looked at signals of a fluorescent dye, which previous researchers had used as an indicator for ROS levels. The team treated bacterial cells with a variety of antibiotics and measured the strength of this signal. Since antibiotics were presumed to increase ROS levels, one would have expected increased concentrations of antibiotics to correlate with stronger signals. However, Lewis' group saw no such correlation.

"But there's a difference between correlation and direct observation," Keren said. In order to support their observations with unequivocal data, the team members physically separated the cells that had stronger fluorescent signals from those with weak signals and treated them both with the same antibiotics. Both populations suffered equivalent cell death.

"The research from Dr. Lewis' group demonstrates that, contrary to current dogma, antibiotics apparently do not kill bacteria through induction of reactive oxygen species," said Steven Projan, vice president for research and development at iMed and head of Infectious Diseases and Vaccines at MedImmune, both subsidiaries of AstraZeneca. "The results shown are rather clear but still leave us with the mystery as to how antibacterial drugs help infected people clear bacterial infections. At this point, we should probably dispense with the 'one size fits all' approach to bacterial killing by antibiotics," said Projan, who was not involved in the research.

With these results, Lewis and Keren hope the field will be able to focus its efforts on understanding the true mechanisms of how antibiotics wipe out bacteria in order to effectively address chronic bacterial infections, one of the most pressing issues facing public health today.

###

END

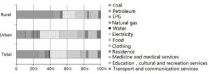

The current international climate policy framework is mainly based on the national and regional level of macroscopic carbon emissions data, such as the regional per capita carbon emissions are often used as the indicator to measure the fairness of carbon emission rights. However, the per capita emissions based on regional macro data can not accurately reveal the low carbon emissions of the poor within the region, and cover up the emission differences among people intra-country and intra-region, the household carbon emission data based on field surveys could compensate for ...

In a long-term study, Prof. Dr. Jürgen Margraf, Alexander von Humboldt Professor for Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy at the RUB, investigated the psychological effects of plastic surgery on approximately 550 patients in cooperation with colleagues from the University of Basel. Patients demonstrated more enjoyment of life, satisfaction and self-esteem after their physical appearance had been surgically altered. The results of the world's largest ever study on this issue are reported by the researchers in the journal "Clinical Psychological Science".

The aim of the ...

Extensive shell fishing and sewerage discharge in river estuaries could have serious consequences for the rare Icelandic black-tailed godwits that feed there. But it is the males that are more likely to suffer, according to new research from the University of East Anglia.

Research published today in the journal Ecology and Evolution reveals very different winter feeding habits between the sexes.

Both males and females mainly consume bivalve molluscs, sea snails and marine worms, probing vigorously into soft estuary mud with their long beaks. But the study shows that ...

Drinking just two cups of coffee a day is associated with the risk of low birth weight. Researchers at Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Sweden, have conducted a study on 59,000 women in collaboration with the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

Expectant mothers who consume caffeine, usually by drinking coffee, are more likely to have babies with lower birth weight than anticipated, given their gestational age. Researchers at Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, conducted a study on 59,000 pregnant Norwegian women in collaboration with the Norwegian ...

This press release is available in German.

Immune system B cells play a crucial role in the defence of pathogens; when they detect such an intruder, they produce antibodies that help to combat the enemy. They concurrently and continuously improve these molecules to more precisely recognize the pathogens. A team of scientists with participation of the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research (HZI) has discovered that during this process the cells are able to advance their own evolution themselves by increasing the selection pressure through previously-produced antibodies. ...

Philadelphia, Pa. (March 11, 2013) - Patients with neck injuries incur increased health and social costs—which also affect their spouses and may begin years before the initial injury, reports a study in the March 1 issue of Spine. The journal is published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a part of Wolters Kluwer Health.

Some individuals and families seem more susceptible to experiencing socioeconomic consequences of neck injury, according to the new research by Dr Poul Jennum of University of Copenhagen and colleagues. Particularly for patients who develop chronic ...

A team of researchers from the National University of Singapore (NUS) led by Professor Loh Kian Ping, Head of the Department of Chemistry at the NUS Faculty of Science, has successfully altered the properties of water, making it corrosive enough to etch diamonds. This was achieved by attaching a layer of graphene on diamond and heated to high temperatures. Water molecules trapped between them become highly corrosive, as opposed to normal water.

This novel discovery, reported for the first time, has wide-ranging industrial applications, from environmentally-friendly degradation ...

AMHERST, Mass. – For hundreds of years, naturalists and scientists have identified new species based on an organism's visible differences. But now, new genetic techniques are revealing that different species can show little, to no visible differences.

In a just-published study, evolutionary biologists at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) combine traditional morphological tests plus genetic techniques to describe new species. Groups of morphologically similar organisms that show very divergent genetics are generally ...

Many Europeans are fretting these days over what they eat, and whether horse meat might have adulterated their pork chops. Food fraud has been dominating headlines globally - calling for new policies in law enforcement and more robust methods for successful food identification and authentication. As companies and manufacturers resort to fraudulent practices to extract more cash from the gullible public, it is estimated that up to 7% of the consumer supply chain contains hidden ingredients (i.e. – not disclosed on the label). And while all too often policymakers seem oblivious ...

These findings are the result of a new study carried out at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. In the study, women who took folic acid supplements from four weeks before conception to eight weeks into pregnancy had a 40 per cent lower risk of giving birth to children with childhood autism (classic autism).

"It appears that the crucial time interval is from four weeks before conception to eight weeks into pregnancy," states Pål Surén, MD and doctoral fellow at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

The study is based on the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort ...