(Press-News.org) PASADENA, Calif.—Imagine that the chips in your smart phone or computer could repair and defend themselves on the fly, recovering in microseconds from problems ranging from less-than-ideal battery power to total transistor failure. It might sound like the stuff of science fiction, but a team of engineers at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), for the first time ever, has developed just such self-healing integrated chips.

The team, made up of members of the High-Speed Integrated Circuits laboratory in Caltech's Division of Engineering and Applied Science, has demonstrated this self-healing capability in tiny power amplifiers. The amplifiers are so small, in fact, that 76 of the chips—including everything they need to self-heal—could fit on a single penny. In perhaps the most dramatic of their experiments, the team destroyed various parts of their chips by zapping them multiple times with a high-power laser, and then observed as the chips automatically developed a work-around in less than a second.

"It was incredible the first time the system kicked in and healed itself. It felt like we were witnessing the next step in the evolution of integrated circuits," says Ali Hajimiri, the Thomas G. Myers Professor of Electrical Engineering at Caltech. "We had literally just blasted half the amplifier and vaporized many of its components, such as transistors, and it was able to recover to nearly its ideal performance."

The team's results appear in the March issue of IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques.

Until now, even a single fault has often rendered an integrated-circuit chip completely useless. The Caltech engineers wanted to give integrated-circuit chips a healing ability akin to that of our own immune system—something capable of detecting and quickly responding to any number of possible assaults in order to keep the larger system working optimally. The power amplifier they devised employs a multitude of robust, on-chip sensors that monitor temperature, current, voltage, and power. The information from those sensors feeds into a custom-made application-specific integrated-circuit (ASIC) unit on the same chip, a central processor that acts as the "brain" of the system. The brain analyzes the amplifier's overall performance and determines if it needs to adjust any of the system's actuators—the changeable parts of the chip.

Interestingly, the chip's brain does not operate based on algorithms that know how to respond to every possible scenario. Instead, it draws conclusions based on the aggregate response of the sensors. "You tell the chip the results you want and let it figure out how to produce those results," says Steven Bowers, a graduate student in Hajimiri's lab and lead author of the new paper. "The challenge is that there are more than 100,000 transistors on each chip. We don't know all of the different things that might go wrong, and we don't need to. We have designed the system in a general enough way that it finds the optimum state for all of the actuators in any situation without external intervention."

Looking at 20 different chips, the team found that the amplifiers with the self-healing capability consumed about half as much power as those without, and their overall performance was much more predictable and reproducible. "We have shown that self-healing addresses four very different classes of problems," says Kaushik Dasgupta, another graduate student also working on the project. The classes of problems include static variation that is a product of variation across components; long-term aging problems that arise gradually as repeated use changes the internal properties of the system; and short-term variations that are induced by environmental conditions such as changes in load, temperature, and differences in the supply voltage; and, finally, accidental or deliberate catastrophic destruction of parts of the circuits.

The Caltech team chose to demonstrate this self-healing capability first in a power amplifier for millimeter-wave frequencies. Such high-frequency integrated chips are at the cutting edge of research and are useful for next-generation communications, imaging, sensing, and radar applications. By showing that the self-healing capability works well in such an advanced system, the researchers hope to show that the self-healing approach can be extended to virtually any other electronic system.

"Bringing this type of electronic immune system to integrated-circuit chips opens up a world of possibilities," says Hajimiri. "It is truly a shift in the way we view circuits and their ability to operate independently. They can now both diagnose and fix their own problems without any human intervention, moving one step closer to indestructible circuits."

INFORMATION:

Along with Hajimiri, Bowers, and Dasgupta, former Caltech postdoctoral scholar Kaushik Sengupta (PhD '12), who is now an assistant professor at Princeton University, is also a coauthor on the paper, "Integrated Self-Healing for mm-Wave Power Amplifiers." A preliminary report of this work won the best paper award at the 2012 IEEE Radio Frequency Integrated Circuits Symposium. The work was funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and the Air Force Research Laboratory.

Creating indestructible self-healing circuits

Caltech engineers build electronic chips that repair themselves

2013-03-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Epigenetics mechanism may help explain effects of mom's nutrition on her children's health

2013-03-12

This press release is available in Spanish.

Pioneering studies by U. S. Department of Agriculture-funded research molecular geneticist Robert A. Waterland are helping explain how the foods that soon-to-be-moms eat in the days and weeks around the time of conception—or what's known as periconceptional nutrition–may affect the way genes function in her children, and her children's health.

In an early study, Waterland and co-investigators examined gene function of 50 healthy children living in rural villages in the West African nation of The Gambia. The study has shaped ...

Study shows how one insect got its wings

2013-03-12

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Scientists have delved deeper into the evolutionary history of the fruit fly than ever before to reveal the genetic activity that led to the development of wings – a key to the insect's ability to survive.

The wings themselves are common research models for this and other species' appendages. But until now, scientists did not know how the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, first sprouted tiny buds that became flat wings.

A cluster of only 20 or so cells present in the fruit fly's first day of larval life was analyzed to connect a gene known to be active ...

Study predicts lag in summer rains over parts of US and Mexico

2013-03-12

A delay in the summer monsoon rains that fall over the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico is expected in the coming decades according to a new study in the Journal of Geophysical Research. The North American monsoon delivers as much as 70 percent of the region's annual rainfall, watering crops and rangelands for an estimated 20 million people.

"We hope this information can be used with other studies to build realistic expectations for water resource availability in the future," said study lead author, Benjamin Cook, a climate scientist with joint appointments ...

Study shows on-pump bypass comparable to off-pump at year mark

2013-03-12

SAN FRANCISCO (March 11, 2013) — Patients who underwent heart bypass surgery without a heart- lung machine did as well one year later as patients whose hearts were connected to a pump during surgery in a study presented today at the American College of Cardiology's 62nd Annual Scientific Session.

CORONARY, an international, multicenter trial of on-pump (with a heart-lung machine) versus off-pump bypass surgery, enrolled 4,752 patients already scheduled to undergo a bypass procedure. The study is the largest to compare the two approaches.

For the primary endpoint of ...

University of Maryland School of Medicine discovers adaptations to explain strategies for survival on Mars

2013-03-12

Research from the University of Maryland School of Medicine has revealed key features in proteins needed for life to function on Mars and other extreme environments. The researchers, funded by NASA, studied organisms that survive in the extreme environment of Antarctica. They found subtle but significant differences between the core proteins in ordinary organisms and Haloarchaea, organisms that can tolerate severe conditions such as high salinity, desiccation, and extreme temperatures. The research gives scientists a window into how life could possibly adapt to exist on ...

Similar outcomes in older patients with on- or off-pump bypass

2013-03-12

SAN FRANCISCO (March 11, 2013) — Older patients did as well after undergoing coronary bypass surgery off-pump as they did with the more costly "on-pump" procedure using a heart-lung machine to circulate blood and oxygen through the body during surgery, according to research presented today at the American College of Cardiology's 62nd Annual Scientific Session.

This large, multicenter trial—the German Off-Pump Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting in Elderly Patients, called GOPCABE—was the first to evaluate on-pump versus off-pump bypass surgery among patients aged 75 or older. ...

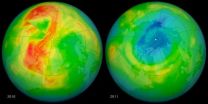

NASA pinpoints causes of 2011 Arctic ozone hole

2013-03-12

A combination of extreme cold temperatures, man-made chemicals and a stagnant atmosphere were behind what became known as the Arctic ozone hole of 2011, a new NASA study finds.

Even when both poles of the planet undergo ozone losses during the winter, the Arctic's ozone depletion tends to be milder and shorter-lived than the Antarctic's. This is because the three key ingredients needed for ozone-destroying chemical reactions —chlorine from man-made chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), frigid temperatures and sunlight— are not usually present in the Arctic at the same time: the ...

NASA's SDO observes Earth, lunar transits in same day

2013-03-12

On March 2, 2013, NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) entered its semiannual eclipse season, a period of three weeks when Earth blocks its view of the sun for a period of time each day. On March 11, however, SDO was treated to two transits. Earth blocked SDO's view of the sun from about 2:15 to 3:45 a.m. EDT. Later in the same day, from around 7:30 to 8:45 a.m. EDT, the moon moved in front of the sun for a partial eclipse.

When Earth blocks the sun, the boundaries of Earth's shadow appear fuzzy, since SDO can see some light from the sun coming through Earth's atmosphere. ...

Angioplasty at hospitals without on-site cardiac surgery safe, effective

2013-03-12

SAN FRANCISCO (March 11, 2013) — Non-emergency angioplasty performed at hospitals without on-site cardiac surgery capability is no less safe and effective than angioplasty performed at hospitals with cardiac surgery services, according to research presented today at the American College of Cardiology's 62nd Annual Scientific Session.

Emergency surgery has become an increasingly rare event following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or angioplasty—a non-surgical procedure used to open narrow or blocked coronary arteries and restore blood flow to the heart. This ...

Single concussion may cause lasting brain damage

2013-03-12

OAK BROOK, Ill. – A single concussion may cause lasting structural damage to the brain, according to a new study published online in the journal Radiology.

"This is the first study that shows brain areas undergo measureable volume loss after concussion," said Yvonne W. Lui, M.D., Neuroradiology section chief and assistant professor of radiology at NYU Langone School of Medicine. "In some patients, there are structural changes to the brain after a single concussive episode."

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, each year in the U.S., 1.7 million ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

New research finds heart health benefits in combining mango and avocado daily

New research finds peanut butter consumption builds muscle power in older adults

Study identifies aging-associated mitochondrial circular RNAs

The brain’s primitive ‘fear center’ is actually a sophisticated mediator

Brain Healthy Campus Collaborative announces winner of first-ever Brain Health Prize

Tokyo Bay’s night lights reveal hidden boundaries between species

As worms and jellyfish wriggle, new AI tools track their neurons

ATG14 identified as a central guardian against liver injury and fibrosis

Research identifies blind spots in AI medical triage

$9M for exploring the fundamental limits of entangled quantum sensor networks

Study shows marine plastic pollution alters octopus predator-prey encounters

Night lights can structure ecosystems

A parasitic origin for the ribosome?

A gold-standard survey of the American mood

Tool for identifying children at risk of speech disorders

How Japanese medical trainees view artificial intelligence in medicine

MambaAlign fusion framework for detecting defects missed by inspection systems

Children born with upper limb difference show the incredible adaptability of the young brain

How bacteria can reclaim lost energy, nutrients, and clean water from wastewater

Fast-paced lives demand faster vision: ecology shapes how “quickly” animals see time

Global warming and heat stress risk close in on the Tour de France

New technology reveals hidden DNA scaffolding built before life ‘switches on’

New study reveals early healthy eating shapes lifelong brain health

Trashing cancer’s ‘undruggable’ proteins

Industrial research labs were invented in Europe but made the U.S. a tech superpower

Enzymes work as Maxwell's demon by using memory stored as motion

Methane’s missing emissions: The underestimated impact of small sources

Beating cancer by eating cancer

How sleep disruption impairs social memory: Oxytocin circuits reveal mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities

Natural compound from pomegranate leaves disrupts disease-causing amyloid

[Press-News.org] Creating indestructible self-healing circuitsCaltech engineers build electronic chips that repair themselves