(Press-News.org) MADISON — For the first time, scientists have transplanted neural cells derived from a monkey's skin into its brain and watched the cells develop into several types of mature brain cells, according to the authors of a new study in Cell Reports. After six months, the cells looked entirely normal, and were only detectable because they initially were tagged with a fluorescent protein.

Because the cells were derived from adult cells in each monkey's skin, the experiment is a proof-of-principle for the concept of personalized medicine, where treatments are designed for each individual.

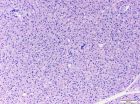

And since the skin cells were not "foreign" tissue, there were no signs of immune rejection — potentially a major problem with cell transplants. "When you look at the brain, you cannot tell that it is a graft," says senior author Su-Chun Zhang, a professor of neuroscience at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. "Structurally the host brain looks like a normal brain; the graft can only be seen under the fluorescent microscope."

Marina Emborg, an associate professor of medical physics at UW-Madison and the lead co-author of the study, says, "This is the first time I saw, in a nonhuman primate, that the transplanted cells were so well integrated, with such a minimal reaction. And after six months, to see no scar, that was the best part."

The cells were implanted in the monkeys "using a state-of-the-art surgical procedure" guided by an MRI image, says Emborg. The three rhesus monkeys used in the study at the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center had a lesion in a brain region that causes the movement disorder Parkinson's disease, which afflicts up to 1 million Americans. Parkinson's is caused by the death of a small number of neurons that make dopamine, a signaling chemical used in the brain.

The transplanted cells came from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS cells), which can, like embryonic stem cells, develop into virtually any cell in the body. iPS cells, however, derive from adult cells rather than embryos.

In the lab, the iPS cells were converted into neural progenitor cells. These intermediate-stage cells can further specialize into the neurons that carry nerve signals, and the glial cells that perform many support and nutritional functions. This final stage of maturation occurred inside the monkey.

Zhang, who was the first in the world to derive neural cells from embryonic stem cells and then iPS cells, says one key to success was precise control over the development process. "We differentiate the stem cells only into neural cells. It would not work to transplant a cell population contaminated by non-neural cells."

Another positive sign was the absence of any signs of cancer, says Zhang — a worrisome potential outcome of stem cell transplants. "Their appearance is normal, and we also used antibodies that mark cells that are dividing rapidly, as cancer cells are, and we do not see that. And when you look at what the cells have become, they become neurons with long axons [conducting fibers], as we'd expect. They also produce oligodendrocytes that are helping build insulating myelin sheaths for neurons, as they should. That means they have matured correctly, and are not cancerous."

The experiment was designed as a proof of principle, says Zhang, who leads a group pioneering the use of iPS cells at the Waisman Center on the UW-Madison campus. The researchers did not transplant enough neurons to replace the dopamine-making cells in the brain, and the animal's behavior did not improve.

Although promising, the transplant technique is a long way from the clinic, Zhang adds. "Unfortunately, this technique cannot be used to help patients until a number of questions are answered: Can this transplant improve the symptoms? Is it safe? Six months is not long enough… And what are the side effects? You may improve some symptoms, but if that leads to something else, then you have not solved the problem."

Nonetheless, the new study represents a real step forward that may benefit human patients suffering from several diseases, says Emborg. "By taking cells from the animal and returning them in a new form to the same animal, this is a first step toward personalized medicine."

The need for treatment is incessant, says Emborg, noting that each year, Parkinson's is diagnosed in 60,000 patients. "I'm gratified that the Parkinson's Disease Foundation took a risk as the primary funder for this small study. Now we want to move ahead and see if this leads to a real treatment for this awful disease."

"It's really the first-ever transplant of iPS cells from a non-human primate back into the same animal, not just in the brain," says Zhang. "I have not seen anybody transplanting reprogrammed iPS cells into the blood, the pancreas or anywhere else, into the same primate. This proof-of-principle study in primates presents hopes for personalized regenerative medicine."

###

— David Tenenbaum, 608-265-8549, djtenenb@wisc.edu

CONTACT: Su-Chun Zhang, szhang4@wisc.edu, 608-265-2543 (prefers email for first contact); Marina Emborg, emborg@primate.wisc.edu, 608-262-9714

NOTE: High-resolution images to accompany this story are available for download at http://www.news.wisc.edu/newsphotos/zhang13.html

NEWPORT, Ore. – Pilot whales that have died in mass strandings in New Zealand and Australia included many unrelated individuals at each event, a new study concludes, challenging a popular assumption that whales follow each other onto the beach and to almost certain death because of familial ties.

Using genetic samples from individuals in large strandings, scientists have determined that both related and unrelated individuals were scattered along the beaches – and that the bodies of mothers and young calves were often separated by large distances.

Results of the study ...

PHILADELPHIA - Brown fat is a hot topic, pardon the pun. Brown fats cells, as opposed to white fat cells, make heat for the body, and are thought to have evolved to help mammals cope with the cold. But, their role in generating warmth might also be applied to coping with obesity and diabetes.

The lab of Patrick Seale, PhD, at the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, studies what proteins guide the development, differentiation, and function of fat cells. Seale and postdoctoral fellow Sona Rajakumari, PhD, along with Jun Wu from the Dana-Farber Cancer ...

Scientists already knew that some social bee species warn their conspecifics when detecting the presence of a predator near their hive, which in turn causes an attack response to the possible predator. Researchers at the University of Tours (France) in collaboration with the Experimental Station of Arid Zones of Almeria (Spain) have now demonstrated that they also use chemical signals to mark those flowers where they have previously been attacked.

Researchers at the University of Tours (France) and the Experimental Station of Arid Zones of Almeria (EEZA-CSIC) conducted ...

Mountain View, Calif. – March 14, 2013 – In the largest ever genome-wide association study on myopia, 23andMe, the leading personal genetics company, identified 20 new genetic associations for myopia, or nearsightedness. The company also replicated two known associations in the study, which was specific to individuals of European ancestry. The study included an analysis of genetic data and survey responses from more than 50,000 23andMe customers and demonstrates that the genetic basis of myopia is complex and affected by multiple genes.

Myopia is the most common eye ...

A new research technique, pioneered by Dr. Maria Angela Franceschini, will be published in JoVE (Journal of Visualized Experiments) on March 14th. Researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School have developed a non-invasive optical measurement system to monitor neonatal brain activity via cerebral metabolism and blood flow.

Of the nearly four million children born in the United States each year, 12% are born preterm, 8% are born with low birth weight, and 1-2% of infants are at risk for death associated with respiratory distress. The result ...

Bangkok, 14 March 2013. CITES plenary today accepted Committee recommendations to list five species of highly traded sharks under the CITES Appendices, along with those for the listing of both manta rays and one species of sawfish. Japan, backed by Gambia and India, unsuccessfully challenged the Committee decision to list the oceanic whitetip shark, while Grenada and China failed in an attempt to reopen debate on listing three hammerhead species. Colombia, Senegal, Mexico and others took the floor to defend Committee decisions to list sharks.

"We are thrilled with this ...

BANGKOK -- March 14, 2013 -- The following statement was issued today by WCS President and CEO Cristian Samper:

The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) today celebrates the decision by an historic, broad group of nations from around the world to list five new sharks, freshwater sawfish, and two manta ray species for protection by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). This vote is a first, critical step in working to ensure that international trade does not threaten the survival of commercially valuable shark and ray ...

The European Parliament recently voted to scrap the controversial discards policy, which has seen fishermen throwing thousands of edible fish and fish waste back into the sea because they have exceeded their quotas.

Scientists at Plymouth University believe this could have a negative impact on some seabirds, which have become used to following the fishing vessels and are increasingly reliant on their discards.

But they say others could return to using foraging as their sole source of food, as long as there are sufficient numbers of fish to meet their needs.

Dr Stephen ...

How you get the chameleon of the molecules to settle on a particular "look" has been discovered by RUB chemists led by Professor Dominik Marx. The molecule CH5+ is normally not to be described by a single rigid structure, but is dynamically flexible. By means of computer simulations, the team from the Centre for Theoretical Chemistry showed that CH5+ takes on a particular structure once you attach hydrogen molecules. "In this way, we have taken an important step towards understanding experimental vibrational spectra in the future", says Dominik Marx. The researchers report ...

A project led by scientists from Royal Holloway University in collaboration with Princeton University, has found evidence of how people form into tribe-like communities on social network sites such as Twitter.

In a paper published in EPJ Data Science, they found that these communities have a common character, occupation or interest and have developed their own distinctive languages.

"This means that by looking at the language someone uses, it is possible to predict which community he or she is likely to belong to, with up to 80% accuracy," said Dr John Bryden from ...