(Press-News.org) A new study from the University of Maryland School of Medicine suggests that depression results from a disturbance in the ability of brain cells to communicate with each other. The study indicates a major shift in our understanding of how depression is caused and how it should be treated. Instead of focusing on the levels of hormone-like chemicals in the brain, such as serotonin, the scientists found that the transmission of excitatory signals between cells becomes abnormal in depression. The research, by senior author Scott M. Thompson, Ph.D., Professor and Interim Chair of the Department of Physiology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, was published online in the March 17 issue of Nature Neuroscience.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, between 2005 and 2008, approximately one in 10 Americans were treated for depression, with women more than twice as likely as men to become depressed. The most common antidepressant medications, such as Prozac, Zoloft and Celexa, work by preventing brain cells from absorbing serotonin, resulting in an increase in its concentration in the brain. Unfortunately, these medications are effective in only about half of patients. Because elevation of serotonin makes some depressed patients feel better, it has been thought for over 50 years that the cause of depression must therefore be an insufficient level of serotonin. The new University of Maryland study challenges that long-standing explanation.

"Dr. Thompson's groundbreaking research could alter the field of psychiatric medicine, changing how we understand the crippling public health problem of depression and other mental illness," says E. Albert Reece, M.D., Ph.D., M.B.A., Vice President for Medical Affairs at the University of Maryland and John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and Dean at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. "This is the type of cutting-edge science that we strive toward at the University of Maryland, where discoveries made in the laboratory can impact the clinical practice of medicine."

Depression affects more than a quarter of all U.S. adults at some point in their lives, and the World Health Organization predicts that by 2020 it will be the second leading cause of disability worldwide. Depression is also the leading risk factor for suicide, which causes twice as many deaths as murder, and is the third leading cause of death for 15-24 year olds.

The first major finding of the study was the discovery that serotonin has a previously unknown ability to strengthen the communication between brain cells. "Like speaking louder to your companion at a noisy cocktail party, serotonin amplifies excitatory interactions in brain regions important for emotional and cognitive function and apparently helps to make sure that crucial conversations between neurons get heard," says Dr. Thompson. "Then we asked, does this action of serotonin play any role in the therapeutic action of drugs like Prozac?"

To understand what might be wrong in the brains of patients with depression and how elevating serotonin might relieve their symptoms, the study team examined the brains of rats and mice that had been repeatedly exposed to various mildly stressful conditions, comparable to the types of psychological stressors that can trigger depression in people.

The researchers could tell that their animals became depressed because they lost their preference for things that are normally pleasurable. For example, normal animals given a choice of drinking plain water or sugar water strongly prefer the sugary solution. Study animals exposed to repeated stress, however, lost their preference for the sugar water, indicating that they no longer found it rewarding. This depression-like behavior strongly mimics one hallmark of human depression, called anhedonia, in which patients no longer feel rewarded by the pleasures of a nice meal or a good movie, the love of their friends and family, and countless other daily interactions.

A comparison of the activity of the animals' brain cells in normal and stressed rats revealed that stress had no effect on the levels of serotonin in the 'depressed' brains. Instead, it was the excitatory connections that responded to serotonin in strikingly different manner. These changes could be reversed by treating the stressed animals with antidepressants until their normal behavior was restored.

"In the depressed brain, serotonin appears to be trying hard to amplify that cocktail party conversation, but the message still doesn't get through," says Dr. Thompson. Using specially engineered mice created by collaborators at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, the study also revealed that the ability of serotonin to strengthen excitatory connections was required for drugs like antidepressants to work.

Sustained enhancement of communication between brain cells is considered one of the major processes underlying memory and learning. The team's observations that excitatory brain cell function is altered in models of depression could explain why people with depression often have difficulty concentrating, remembering details, or making decisions. Additionally, the findings suggest that the search for new and better antidepressant compounds should be shifted from drugs that elevate serotonin to drugs that strengthen excitatory connections.

"Although more work is needed, we believe that a malfunction of excitatory connections is fundamental to the origins of depression and that restoring normal communication in the brain, something that serotonin apparently does in successfully treated patients, is critical to relieving the symptoms of this devastating disease," Dr. Thompson explains.

### END

University of Maryland School of Medicine finds depression stems from miscommunication between brain cells

Study challenges role of serotonin in depression, opens possibilities for new therapies

2013-03-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Blind flies without recycling

2013-03-18

Bochum, 18.3.2013

In the fruit fly Drosophila, the functions of the three enzymes Tan, Ebony and Black are closely intertwined - among other things they are involved in neurotransmitter recycling for the visual process. RUB researchers from the Department of Biochemistry showed for the first time that flies cannot see without this recycling. Their analysis of the enzyme Black also raises new questions as to its function. Anna Ziegler, Florian Brüsselbach and Bernhard Hovemann report in the „Journal of Comparative Neurology", which chose this topic as cover story.

Tan, ...

New database to speed genetic discoveries

2013-03-18

A new online database combining symptoms, family history and genetic sequencing information is speeding the search for diseases caused by a single rogue gene. As described in an article in the May issue of Human Mutation, the database, known as PhenoDB, enables any clinician to document cases of unusual genetic diseases for analysis by researchers at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine or the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. If a review committee agrees that the patient may indeed have a previously unknown genetic disease, the patient and some of his or ...

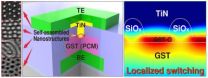

Self-assembled nanostructures enable a low-power phase-change memory for mobile electronic devices

2013-03-18

Daejeon, Republic of Korea, March 18, 2013 -- Nonvolatile memory that can store data even when not powered is currently used for portable electronics such as smart phones, tablets, and laptop computers. Flash memory is a dominant technology in this field, but its slow writing and erasing speed has led to extensive research into a next-generation nonvolatile memory called Phase-Change Random Access Memory (PRAM), as PRAM's operating speed is 1,000 times faster than that of flash memory.

PRAM uses reversible phase changes between the crystalline (low resistance) and amorphous ...

Scientists investigate potential markers for a response to sunitinib in patients with metastatic RCC

2013-03-18

Milan, 18 March 2013 – Markers such as CA9, CD31, CD34 and VEGFR1/2 in the primary tumours might serve as predictors of a good response to a sunitinib treatment in patients with metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), according to a new study to be presented at the 28th Annual EAU Congress currently on-going in Milan.

"The inactivation of the von Hippel-Lindau gene (VHL) is a common event in ccRCC and finally leads to the induction of HIF1α target genes such as CA9 and VEGF," write the authors. "Besides VEGF, the VEGF and PDGF receptors also play an important ...

Six Nations Rugby Union: Were the gloves off?

2013-03-18

Drs Lewis and Carré in the University's Department of Mechanical Engineering have been measuring the dynamic friction between the material of the ball and the skin on the fingertips and palm, and the mitts that some players choose to wear under different weather conditions. They're looking to answer one question: what's the best way to ensure that players don't fumble the ball?

"Catching and handling a ball with great skill and confidence is practically second nature to players at this level," says Dr Lewis. "But handling errors are still seen in professional rugby games ...

UM researcher revolutionizing scientific communication, one tweet at a time

2013-03-18

CORAL GABLES, FL (March 18, 2012) -- University of Miami (UM) doctoral student in Environmental Science and Policy, David Shiffman was invited to tweet updates in real-time, at the International Congress of Conservation Biology, New Zealand, 2011. As a result, more than 100,000 twitter users worldwide saw at least one tweet from the conference, and nearly 200 people from more than 40 countries, on six continents shared at least one tweet from the conference -- greatly exceeding the number of conference attendees.

"While live-tweeting is not a new phenomenon, ...

Antarctica's first whale skeleton found with 9 new deep-sea species

2013-03-18

Marine biologists have, for the first time, found a whale skeleton on the ocean floor near Antarctica, giving new insights into life in the sea depths. The discovery was made almost a mile below the surface in an undersea crater and includes the find of at least nine new species of deep-sea organisms thriving on the bones.

The research, involving the University of Southampton, Natural History Museum, British Antarctic Survey, National Oceanography Centre (NOC) and Oxford University, is published today in Deep-Sea Research II: Topical Studies in Oceanography.

"The planet's ...

Significant contribution of Greenland's peripheral glaciers to sea-level rise

2013-03-18

The scientists looked at glaciers which behave independently from the ice sheet, despite having some physical connection to it, and those which are not connected at all.

The discovery, just published in Geophysical Research Letters, is important as it will help scientists improve the predictions of the future contribution of Greenland's ice to sea-level rise.

Using lasers which measure the height of the ice from space, and a recently completed inventory of Greenland's glaciers and ice caps, scientists from the European-funded ice2sea programme, were able to determine ...

Male lions use ambush hunting strategy

2013-03-18

Washington, D.C.— It has long been believed that male lions are dependent on females when it comes to hunting. But new evidence suggests that male lions are, in fact, very successful hunters in their own right. A new report from a team including Carnegie's Scott Loarie and Greg Asner shows that male lions use dense savanna vegetation for ambush-style hunting in Africa. Their work is published in Animal Behavior.

Female lions have long been observed to rely on cooperative strategies to hunt their prey. While some studies demonstrated that male lions are as capable at hunting ...

Pneumonia patients nearly twice as likely to suffer from depression, impairments

2013-03-18

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — The long-term consequences of pneumonia can be more detrimental to a person's health than having a heart attack, according to joint research from the University of Michigan Health System and University of Washington School of Medicine.

Older adults who are hospitalized for pneumonia have a significantly higher risk of new problems that affect their ability to care for themselves, and the effects are comparable to those who survive a heart attack or stroke, according to the new findings in the American Journal of Medicine.

"Pneumonia is clearly not ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Tundra tongue: The science behind a very cold mistake

Targeting a dangerous gut infection

Scientists successfully harvest chickpeas from “moon dirt”

Teen aggression a warning sign for faster aging later in life

Study confirms food fortification is highly cost-effective in fighting hidden hunger across 63 countries

Special issue elevates disease ecology in marine management

A kaleidoscope of cosmic collisions: the new catalogue of gravitational signals from LIGO, Virgo and KAGRA

New catalog more than doubles the number of gravitational-wave detections made by LIGO, Virgo, and KAGRA observatories

Antifibrotic drug shows promise for premature ovarian insufficiency

Altered copper metabolism is a crucial factor in inflammatory bone diseases

Real-time imaging of microplastics in the body improves understanding of health risks

Reconstructing the world’s ant diversity in 3D

UMD entomologist helps bring the world’s ant diversity to life in 3D imagery

ESA’s Mars orbiters watch solar superstorm hit the Red Planet

The secret lives of catalysts: How microscopic networks power reactions

Molecular ‘catapult’ fires electrons at the limits of physics

Researcher finds evidence supporting sucrose can help manage painful procedures in infants

New study identifies key factors supporting indigenous well-being

Bureaucracy Index 2026: Business sector hit hardest

ECMWF’s portable global forecasting model OpenIFS now available for all

Yale study challenges notion that aging means decline, finds many older adults improve over time

Korean researchers enable early detection of brain disorders with a single drop of saliva!

Swipe right, but safer

Duke-NUS scientists identify more effective way to detect poultry viruses in live markets

Low-intensity treadmill exercise preconditioning mitigates post-stroke injury in mouse models

How moss helped solve a grave-robbing mystery

How much sleep do teens get? Six-seven hours.

Patients regain weight rapidly after stopping weight loss drugs – but still keep off a quarter of weight lost

GLP-1 diabetes drugs linked to reduced risk of addiction and substance-related death

Councils face industry legal threats for campaigns warning against wood burning stoves

[Press-News.org] University of Maryland School of Medicine finds depression stems from miscommunication between brain cellsStudy challenges role of serotonin in depression, opens possibilities for new therapies