(Press-News.org) Milan, 16 March 2013 - At the 28th Annual EAU Congress currently ongoing in Milan until Tuesday, W. Tan and colleagues presented their study on neoadjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy which showed that epigenetic changes are potential key drivers in the development of chemo resistance in bladder cancer.

Neoadjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy is recommended for patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer. Cisplatin-based regimes have similar efficacy with complete response in 30% a survival advantage if 16% (HR, 0.84;CI 0.72 to 0.99), wrote Tan of the UCL, Dept. of Surgery and Interventional Science in London, the UK.

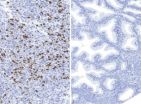

According to the researchers, the ability to identify a biomarker which is able to predict response to treatment would increase pathological complete response rates and spare nonresponders adverse events of chemotherapy. DNA hypermethylation has been implicated in chemotherapy resistance in cancers.

"We hypothesised that DNA methylation may not only represent the mechanisms for the acquisition of resistance, but may also be a potential biomarker to predict response to platinum based chemotherapy in bladder cancer," wrote Tan, lead author of the study titled "Epigenetic alterations associated with neo-adjuvant chemotherapy resistance in bladder cancer."

In the study, DNA was extracted from 48 muscular invasive bladder tumours, taken prior to the patient to receiving a platinum based neo-adjuvant chemotherapy, all tumours had >80% tumour content. 1ug of DNA was bisulphite converted using the EZDNA Bisulfite Conversion Kit (Zymo Research). Genome-wide DNA methylation profiles were generated using the Infinium HumanMethylation 450K BeadChip (Illumina).

According to the researchers, the analysis suggests acquired resistance is associated with global hypermethylation in both primary tumours and paired cell lines. Singular value decomposition (SVD) analysis revealed the strongest methylation signature to be associated with chemotherapy response (p= END

UK study: Epigenetic changes play a key role in development of chemo resistance in BCa

2013-03-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New study points to the aggressive potential of small kidney tumors, advocates treatment

2013-03-18

Milan, 16 March 2013 – Small kidney tumours have an agressive potential and should be treated, according to a the results of a large multicentre study presented at the 28th Annual EAU Congress in Milan.

"Many clinicians regard small renal cell cancer as having a benign biologic behavior and non-operative surveillance protocols are often being used in patients with small renal tumours," write the authors in the findings. "The aim of this large retrospective multi-centre study was to evaluate the prevalence of locally advanced growth and distant metastases in patients with ...

Where, oh where, has the road kill gone?

2013-03-18

Millions of birds die in the US each year as they collide with moving vehicles, but things have been looking up, at least in the case of cliff swallows. Today's swallows are hit less often, thanks to shorter wingspans that may help them take off more quickly and pivot away from passing cars. The findings, reported in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on March 18, show that urban environments can be evolutionary hotspots.

"Evolution is an ongoing process, and all this—roads, SUVs, and all—is part of nature or 'the wild'; they exert selection pressures in a way we ...

Putting the clock in 'cock-a-doodle-doo'

2013-03-18

Of course, roosters crow with the dawn. But are they simply reacting to the environment, or do they really know what time of day it is? Researchers reporting on March 18 in Current Biology, a Cell Press publication, have evidence that puts the clock in "cock-a-doodle-doo" (or "ko-ke-kok-koh," as they say in the research team's native Japan).

"'Cock-a-doodle-doo' symbolizes the break of dawn in many countries," says Takashi Yoshimura of Nagoya University. "But it wasn't clear whether crowing is under the control of a biological clock or is simply a response to external ...

How some prostate tumors resist treatment -- and how it might be fixed

2013-03-18

LA JOLLA, Calif., March 18, 2013 – Hormonal therapies can help control advanced prostate cancer for a time. However, for most men, at some point their prostate cancer eventually stops responding to further hormonal treatment. This stage of the disease is called androgen-insensitive or castration-resistant prostate cancer. In a study published March 18 in Cancer Cell, a team led by researchers at Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute (Sanford-Burnham) found a mechanism at play in androgen-insensitive cells that enables them to survive treatment. They discovered that ...

Oral estrogen hormone therapy linked to increased risk of gallbladder surgery in menopausal women

2013-03-18

Oral estrogen therapy for menopausal women is associated with an increased risk of gallbladder surgery, according to a large-scale study of more than 70 000 women in France published in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal)

Women who took estrogen therapy through skin patches or gels did not appear to be at increased risk.

Gallstone disease is common in developed countries, and women over age 50 are most at risk. Other risk factors include obesity, diabetes, high cholesterol, poor diet and having given birth to two or more children.

A large study of 70 928 ...

Blood protein able to detect higher risk of cardiovascular events

2013-03-18

Higher levels of pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A) were associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events in people with cardiac chest pain that developed as a result of heart disease/coronary artery disease, according to a study published in CMAJ.

PAPP-A, used to screen for Down syndrome in pregnant women, has been suggested as a marker of unstable plaque in coronary arteries.

The study was conducted in 2568 patients in Tübingen, Germany, to determine if the presence of PAPP-A could help predict cardiovascular events. The study included patients ...

Training program developed by U of A medical researchers leads to police using less force

2013-03-18

Researchers with the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry designed a one-day training program for the Edmonton Police Service that resulted in officers being more likely to quickly identify mental health issues during a call, and less likely to use physical force or a weapon in those situations. The training resulted in long-term behaviour change in the officers and saved the police force money because mental health-related calls were dealt with more efficiently.

The pilot study published in the open access and peer-reviewed journal, Frontiers in Psychiatry, noted the following ...

Researchers trap light, improve laser potential of MEH-PPV polymer

2013-03-18

Researchers from North Carolina State University have come up with a low-cost way to enhance a polymer called MEH-PPV's ability to confine light, advancing efforts to use the material to convert electricity into laser light for use in photonic devices.

"Think of a garden hose. If it has holes in it, water springs out through a million tiny leaks. But if you can eliminate those leaks, you confine the water in the hose and improve the water pressure. We've plugged the holes that were allowing light to leak out of the MEH-PPV," says Dr. Lewis Reynolds, a teaching associate ...

Astrocyte signaling sheds light on stroke research

2013-03-18

BOSTON (March 18, 2013) — New research published in The Journal of Neuroscience suggests that modifying signals sent by astrocytes, our star-shaped brain cells, may help to limit the spread of damage after an ischemic brain stroke. The study in mice, by neuroscientists at Tufts University School of Medicine, determined that astrocytes play a critical role in the spread of damage following stroke.

The National Heart Foundation reports that ischemic strokes account for 87% of strokes in the United States. Ischemic strokes are caused by a blood clot that forms and travels ...

University of Maryland School of Medicine finds depression stems from miscommunication between brain cells

2013-03-18

A new study from the University of Maryland School of Medicine suggests that depression results from a disturbance in the ability of brain cells to communicate with each other. The study indicates a major shift in our understanding of how depression is caused and how it should be treated. Instead of focusing on the levels of hormone-like chemicals in the brain, such as serotonin, the scientists found that the transmission of excitatory signals between cells becomes abnormal in depression. The research, by senior author Scott M. Thompson, Ph.D., Professor and Interim Chair ...