(Press-News.org) Of course, roosters crow with the dawn. But are they simply reacting to the environment, or do they really know what time of day it is? Researchers reporting on March 18 in Current Biology, a Cell Press publication, have evidence that puts the clock in "cock-a-doodle-doo" (or "ko-ke-kok-koh," as they say in the research team's native Japan).

"'Cock-a-doodle-doo' symbolizes the break of dawn in many countries," says Takashi Yoshimura of Nagoya University. "But it wasn't clear whether crowing is under the control of a biological clock or is simply a response to external stimuli."

That's because other things—a car's headlights, for instance—will set a rooster off, too, at any time of day. To find out whether the roosters' crowing is driven by an internal biological clock, Yoshimura and his colleague Tsuyoshi Shimmura placed birds under constant light conditions and turned on recorders to listen and watch.

Under round-the-clock dim lighting, the roosters kept right on crowing each morning just before dawn, proof that the behavior is entrained to a circadian rhythm. The roosters' reactions to external events also varied over the course of the day.

In other words, predawn crowing and the crowing that roosters do in response to other cues both depend on a circadian clock.

The findings are just the start of the team's efforts to unravel the roosters' innate vocalizations, which aren't learned like songbird songs or human speech, the researchers say.

"We still do not know why a dog says 'bow-wow' and a cat says 'meow,' Yoshimura says. "We are interested in the mechanism of this genetically controlled behavior and believe that chickens provide an excellent model."

INFORMATION:

INFORMATION:

Current Biology, Shimmura et al.: "Circadian clock determines the timing of rooster crowing."

Putting the clock in 'cock-a-doodle-doo'

2013-03-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

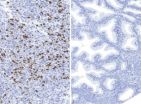

How some prostate tumors resist treatment -- and how it might be fixed

2013-03-18

LA JOLLA, Calif., March 18, 2013 – Hormonal therapies can help control advanced prostate cancer for a time. However, for most men, at some point their prostate cancer eventually stops responding to further hormonal treatment. This stage of the disease is called androgen-insensitive or castration-resistant prostate cancer. In a study published March 18 in Cancer Cell, a team led by researchers at Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute (Sanford-Burnham) found a mechanism at play in androgen-insensitive cells that enables them to survive treatment. They discovered that ...

Oral estrogen hormone therapy linked to increased risk of gallbladder surgery in menopausal women

2013-03-18

Oral estrogen therapy for menopausal women is associated with an increased risk of gallbladder surgery, according to a large-scale study of more than 70 000 women in France published in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal)

Women who took estrogen therapy through skin patches or gels did not appear to be at increased risk.

Gallstone disease is common in developed countries, and women over age 50 are most at risk. Other risk factors include obesity, diabetes, high cholesterol, poor diet and having given birth to two or more children.

A large study of 70 928 ...

Blood protein able to detect higher risk of cardiovascular events

2013-03-18

Higher levels of pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A) were associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events in people with cardiac chest pain that developed as a result of heart disease/coronary artery disease, according to a study published in CMAJ.

PAPP-A, used to screen for Down syndrome in pregnant women, has been suggested as a marker of unstable plaque in coronary arteries.

The study was conducted in 2568 patients in Tübingen, Germany, to determine if the presence of PAPP-A could help predict cardiovascular events. The study included patients ...

Training program developed by U of A medical researchers leads to police using less force

2013-03-18

Researchers with the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry designed a one-day training program for the Edmonton Police Service that resulted in officers being more likely to quickly identify mental health issues during a call, and less likely to use physical force or a weapon in those situations. The training resulted in long-term behaviour change in the officers and saved the police force money because mental health-related calls were dealt with more efficiently.

The pilot study published in the open access and peer-reviewed journal, Frontiers in Psychiatry, noted the following ...

Researchers trap light, improve laser potential of MEH-PPV polymer

2013-03-18

Researchers from North Carolina State University have come up with a low-cost way to enhance a polymer called MEH-PPV's ability to confine light, advancing efforts to use the material to convert electricity into laser light for use in photonic devices.

"Think of a garden hose. If it has holes in it, water springs out through a million tiny leaks. But if you can eliminate those leaks, you confine the water in the hose and improve the water pressure. We've plugged the holes that were allowing light to leak out of the MEH-PPV," says Dr. Lewis Reynolds, a teaching associate ...

Astrocyte signaling sheds light on stroke research

2013-03-18

BOSTON (March 18, 2013) — New research published in The Journal of Neuroscience suggests that modifying signals sent by astrocytes, our star-shaped brain cells, may help to limit the spread of damage after an ischemic brain stroke. The study in mice, by neuroscientists at Tufts University School of Medicine, determined that astrocytes play a critical role in the spread of damage following stroke.

The National Heart Foundation reports that ischemic strokes account for 87% of strokes in the United States. Ischemic strokes are caused by a blood clot that forms and travels ...

University of Maryland School of Medicine finds depression stems from miscommunication between brain cells

2013-03-18

A new study from the University of Maryland School of Medicine suggests that depression results from a disturbance in the ability of brain cells to communicate with each other. The study indicates a major shift in our understanding of how depression is caused and how it should be treated. Instead of focusing on the levels of hormone-like chemicals in the brain, such as serotonin, the scientists found that the transmission of excitatory signals between cells becomes abnormal in depression. The research, by senior author Scott M. Thompson, Ph.D., Professor and Interim Chair ...

Blind flies without recycling

2013-03-18

Bochum, 18.3.2013

In the fruit fly Drosophila, the functions of the three enzymes Tan, Ebony and Black are closely intertwined - among other things they are involved in neurotransmitter recycling for the visual process. RUB researchers from the Department of Biochemistry showed for the first time that flies cannot see without this recycling. Their analysis of the enzyme Black also raises new questions as to its function. Anna Ziegler, Florian Brüsselbach and Bernhard Hovemann report in the „Journal of Comparative Neurology", which chose this topic as cover story.

Tan, ...

New database to speed genetic discoveries

2013-03-18

A new online database combining symptoms, family history and genetic sequencing information is speeding the search for diseases caused by a single rogue gene. As described in an article in the May issue of Human Mutation, the database, known as PhenoDB, enables any clinician to document cases of unusual genetic diseases for analysis by researchers at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine or the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. If a review committee agrees that the patient may indeed have a previously unknown genetic disease, the patient and some of his or ...

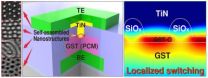

Self-assembled nanostructures enable a low-power phase-change memory for mobile electronic devices

2013-03-18

Daejeon, Republic of Korea, March 18, 2013 -- Nonvolatile memory that can store data even when not powered is currently used for portable electronics such as smart phones, tablets, and laptop computers. Flash memory is a dominant technology in this field, but its slow writing and erasing speed has led to extensive research into a next-generation nonvolatile memory called Phase-Change Random Access Memory (PRAM), as PRAM's operating speed is 1,000 times faster than that of flash memory.

PRAM uses reversible phase changes between the crystalline (low resistance) and amorphous ...