(Press-News.org)

VIDEO:

This video contains more on the pediatric bone cancer preclinical study.

Click here for more information.

BOSTON - Researchers have identified an important signaling pathway that, when blocked, significantly decreases the spread of pediatric bone cancer.

In their study, researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Children's Cancer Hospital in Houston found that blocking the Notch pathway in mice decreased metastases in the lungs 15-fold. The results of a series of pre-clinical studies were reported Sunday in an oral presentation at the 42nd Congress of the International Society of Pediatric Oncology.

Their research showed that the Notch pathway and Hes1 gene play a key role in promoting the metastasis of osteosarcoma, the most common form of bone cancer in children.

Approximately 400 children and teens under the age of 20 are diagnosed with osteosarcoma annually, and the majority present with cancer that has already metastasized. The primary destination for the cancer to spread is to the lungs, which accounts for more than 35 percent of pediatric patients dying from osteosarcoma.

"Knowing the initial results from blocking Notch in mice, we are encouraged to keep investigating the entire metastasis process, so we can find additional therapies and targets to prevent cancer from spreading and growing," said Dennis Hughes, M.D., Ph.D., lead investigator and assistant professor at MD Anderson Children's Cancer Hospital.

In addition to Notch and Hes1's role in metastasis, Hughes believes that their expression can be correlated with a patient's prognosis. Hughes conducted a small retrospective study looking at patient samples, and 39 percent of patients with high expression levels of Hes1 survived 10 years versus the 60 percent survival rate for patients who had lower levels.

Ongoing research is studying the impact of various therapies, such as Gamma-secretase inhibitors and histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, that regulate the Notch pathway and have the potential to affect cancer cell survival. Hughes found that HDAC inhibitors actually increased the Notch pathway in osteosarcoma cells that had low Hes1 expression, which was an unfavorable response in that sample group. However, for cells that presented with high Hes1 expression, where Notch was already maximized, the HDAC inhibitors led to osteosarcoma cell death.

"By defining vital signaling pathways in bone sarcomas, we hope small molecule inhibitors can be applied, leading to longer survival and reducing morbidity and late effects from intensive chemotherapy," said Hughes.

"We also hope these new findings may apply to other solid tumors such as breast, prostate, colon and more, but we'll need additional research to determine whether or not that is the case," he added.

INFORMATION:

Primary funding for the studies was provided through the Physician-Scientist Program at MD Anderson along with additional support from the Jori Zemel Children's Bone Tumor Foundation, Hope Street Kids Foundation and Joan Alexander Fund. Other collaborators include Pingyu Zhang, Ph.D., Yanwen Yang, Daniela Katz, M.D., and Patrick Zweidler-McKay, M.D., Ph.D., from MD Anderson Cancer Center as well as Dafydd Thomas, M.D., Ph.D., from the University of Michigan Medical Center.

About MD Anderson

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston ranks as one of the world's most respected centers focused on cancer patient care, research, education and prevention. MD Anderson is one of only 40 comprehensive cancer centers designated by the National Cancer Institute. For seven of the past nine years, including 2010, MD Anderson has ranked No. 1 in cancer care in "America's Best Hospitals," a survey published annually in U.S. News & World Report.

About MD Anderson Children's Cancer Hospital

The University of Texas MD Anderson Children's Cancer Hospital has been serving children, adolescents and young adults for more than 65 years. In addition to the groundbreaking research and quality of treatment available to pediatric patients, the nationally ranked Children's Cancer Hospital provides comprehensive programs that help children lead more normal lives during and after treatment. For further information, visit the Children's Cancer Hospital Web site at www.mdanderson.org/children

Researchers find pathway that drives spread of pediatric bone cancer in preclinical studies

2010-10-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

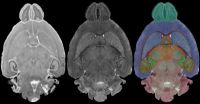

Mouse brain seen in sharpest detail ever

2010-10-26

DURHAM, N.C. – The most detailed magnetic resonance images ever obtained of a mammalian brain are now available to researchers in a free, online atlas of an ultra-high-resolution mouse brain, thanks to work at the Duke Center for In Vivo Microscopy.

In a typical clinical MRI scan, each pixel in the image represents a cube of tissue, called a voxel, which is typically 1x1x3 millimeters. "The atlas images, however, are more than 300,000 times higher resolution than an MRI scan, with voxels that are 20 micrometers on a side," said G. Allan Johnson, Ph.D., who heads the ...

Penn study identifies molecular guardian of cell's RNA

2010-10-26

PHILADELPHIA - When most genes are transcribed, the nascent RNAs they produce are not quite ready to be translated into proteins - they have to be processed first. One of those processes is called splicing, a mechanism by which non-coding gene sequences are removed and the remaining protein-coding sequences are joined together to form a final, mature messenger RNA (mRNA), which contains the recipe for making a protein.

For years, researchers have understood the roles played by the molecular machines that carry out the splicing process. But, as it turns out, one of those ...

UI study investigates variability in men's recall of sexual cues

2010-10-26

Even if a woman is perfectly clear in expressing sexual interest or rejection, young men vary in their ability to remember the cues, a new University of Iowa study shows.

Overall, college-age men were quite good at recalling whether their female peers – in this case, represented through photos – showed interest. Their memories were especially sharp if the model happened to be good looking, dressed more provocatively, and conveyed interest through an inviting expression or posture.

But as researchers examined variations in sexual-cue recall, they found two noteworthy ...

Genetic markers offer new clues about how malaria mosquitoes evade eradication

2010-10-26

VIDEO:

Boston College DeLuca Professor of Biology Marc A.T. Muskavitch discusses his latest malaria research, published in the journal Science. Muskavitch and an international team of researchers developed the first high-resolution...

Click here for more information.

CHESTNUT HILL, Mass. (10/25/2010) – The development and first use of a high-density SNP array for the malaria vector mosquito have established 400,000 genetic markers capable of revealing new insights into how ...

Microwave oven key to self-assembly process meeting semi-conductor industry need

2010-10-26

Thanks to a microwave oven, the fundamental nanotechnology process of self assembly may soon replace the lithographic processing use to make the ubiquitous semi-conductor chips. By using microwaves, researchers at Canada's National Institute for Nanotechnology (NINT) and the University of Alberta have dramatically decreased the cooking time for a specific molecular self-assembly process used to assemble block copolymers, and have now made it a viable alternative to the conventional lithography process for use in patterning semi-conductors. When the team of chemists and ...

Heat acclimation benefits athletic performance

2010-10-26

Turning up the heat might be the best thing for athletes competing in cool weather, according to a new study by human physiology researchers at the University of Oregon.

Published in the October issue of the Journal of Applied Physiology, the paper examined the impact of heat acclimation to improve athletic performance in hot and cool environments.

Researchers conducted exercise tests on 12 highly trained cyclists -- 10 males and two females -- before and after a 10-day heat acclimation program. Participants underwent physiological and performance tests under both ...

Unexpected findings of lead exposure may lead to treating blindness

2010-10-26

HOUSTON, Oct. 25, 2010 – Some unexpected effects of lead exposure that may one day help prevent and reverse blindness have been uncovered by a University of Houston (UH) professor and his team.

Donald A. Fox, a professor of vision sciences in UH's College of Optometry (UHCO), described his team's findings in a paper titled "Low-Level Gestational Lead Exposure Increases Retinal Progenitor Cell Proliferation and Rod Photoreceptor and Bipolar Cell Neurogenesis in Mice," published recently online in Environmental Health Perspectives and soon to be published in the print ...

Rice hulls a sustainable drainage option for greenhouse growers

2010-10-26

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - Greenhouse plant growers can substitute rice hulls for perlite in their media without the need for an increase in growth regulators, according to a Purdue University study.

Growing media for ornamental plants often consists of a soilless mix of peat and perlite, a processed mineral used to increase drainage. Growers also regularly use plant-growth regulators to ensure consistent and desired plant characteristics such as height to meet market demands. Organic substitutes for perlite like tree bark have proven difficult because they absorb the plant-growth ...

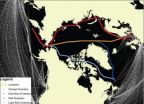

As Arctic warms, increased shipping likely to accelerate climate change

2010-10-26

As the ice-capped Arctic Ocean warms, ship traffic will increase at the top of the world. And if the sea ice continues to decline, a new route connecting international trading partners may emerge -- but not without significant repercussions to climate, according to a U.S. and Canadian research team that includes a University of Delaware scientist.

Growing Arctic ship traffic will bring with it air pollution that has the potential to accelerate climate change in the world's northern reaches. And it's more than a greenhouse gas problem -- engine exhaust particles could ...

UF research gives clues about carbon dioxide patterns at end of Ice Age

2010-10-26

GAINESVILLE, Fla. — New University of Florida research puts to rest the mystery of where old carbon was stored during the last glacial period. It turns out it ended up in the icy waters of the Southern Ocean near Antarctica.

The findings have implications for modern-day global warming, said Ellen Martin, a UF geological sciences professor and an author of the paper, which is published in this week's journal Nature Geoscience.

"It helps us understand how the carbon cycle works, which is important for understanding future global warming scenarios," she said. "Ultimately, ...