The technique is described in a study to be published March 20 in Science Translational Medicine. Testing the new imaging method in humans is probably three to five years off.

Human and animal trials in which stem cells were injected into cardiac tissue to treat severe heart attacks or substantial heart failure have largely yielded poor results, said Sam Gambhir, PhD, MD, senior author of the study and professor and chair of radiology. "We're arguing that the failure is at least partly due to faulty initial placement," he said. "You can use ultrasound to visualize the needle through which you deliver stem cells to the heart. But once those cells leave the needle, you've lost track of them."

As a result, key questions go unanswered: Did the cells actually get to the heart wall? If they did, did they stay there, or did they diffuse away from the heart? If they got there and remained there, for how long did they stay alive? Did they replicate and develop into heart tissue?

"All stem cell researchers want to get the cells to the target site, but up until now they've had to shoot blindly," said Gambhir, who is also the Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Professor in Cancer Research and director of the Molecular Imaging Program at Stanford. "With this new technology, they wouldn't have to. For the first time, they would be able to observe in real time exactly where the stem cells they've injected are going and monitor them afterward. If you inject stem cells into a person and don't see improvement, this technique could help you figure out why and tweak your approach to make the therapy better."

Therapeutic stem cells' vague initial positioning is just part of the problem. No "signature" distinguishes these cells from other cells in the patient's body, so once released from the needle tip they can't be tracked afterward. If, in the weeks following stem cells' infusion into the heart, its beating rhythm or pumping prowess has failed to improve — so far, more often the case than not — you don't know why. That ambiguity, perpetuated by the absence of decent imaging tools, stifles researchers' ability to optimize their therapeutic approach.

The new technique employs a trick that marks stem cells so they can be tracked by standard ultrasound as they're squeezed out of the needle, allowing their more precise guidance to the spot they're intended to go, and then monitored by magnetic-resonance imaging for weeks afterward.

To make this possible, the Gambhir lab designed and produced a specialized imaging agent in the form of nanoparticles whose diameters clustered in the vicinity of just below one-third of a micron — less than one-three-thousandth the width of a human hair, or one-thirtieth the diameter of a red blood cell. The acoustical characteristics of the nanoparticles' chief constituent, silica, allowed them to be visualized by ultrasound; they were also doped with the rare-earth element gadolinium, an MRI contrast agent.

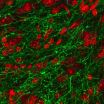

The Stanford group showed that mesenchymal stem cells — a class of cells often used in heart-regeneration research — were able to ingest and store the nanoparticles without losing any of their ability to survive, replicate and differentiate into living heart cells. The nanoparticles were impregnated with a fluorescent material, so Gambhir's team could determine which mesenchymal stem cells gobbled them up. (Mesenchymal stem cells, which are able to differentiate into beating heart cells, can sometimes be harvested from the very patients about to undergo a procedure. This could, in principle, alleviate concerns about the cells being rejected by a patient's immune system.)

Upon infusing the imaging-agent-loaded stem cells from mice, pigs or humans into the hearts of healthy mice, the scientists could watch the cells via ultrasound after they left the needle tip and, therefore, better direct them to the targeted area of the heart wall. Two weeks later, the team could still get a strong MRI signal from the cells. (Eventually, the continued division of the healthy infused stem cells diluted the signal to below the MRI detection limit.)

"There was some early skepticism about whether this would work," said the study's lead author, Jesse Jokerst, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar in Gambhir's lab. "Because the particles were so small, we weren't expecting much signal strength." But once ingested, the particles clumped together inside the cells, reflecting ultrasound waves much more dramatically and providing a surprisingly strong signal, Jokerst said.

"We got lucky," Gambhir said. "Sometimes taking risks pays off."

Using the new agent, the Stanford investigators were able to detect as few as 70,000 of the stem cells by ultrasound and as few as 250,000 by MRI. Either number is tiny in comparison to the tens or hundreds of millions of stem cells being infused into human hearts in clinical trials today, Gambhir said.

No signs of toxicity or behavior differences were seen in mice receiving the agent-containing stem cells compared with control animals receiving stem cells without the agent, he said. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved nanoparticles for other applications, and silicon is considered relatively nontoxic and has been used in the clinic. Gadolinium, which can be toxic at high doses, is clinically approved by the FDA in doses much greater than would be necessary for this new imaging procedure, even if hundreds of millions of stem cells were involved. Still, further toxicity tests will be needed, said Gambhir.

The mice used in this study were all healthy, Jokerst pointed out. The next step, he said, is tests on mice or pigs with analogs of human heart damage, as well as detailed toxicity studies of the nanoparticles.

Stem-cell therapy for damaged hearts won't be cheap anytime in the foreseeable future; it will certainly cost several tens of thousands of dollars per procedure. But, said Gambhir, a successful intervention could be cost-effective because, as a one-time delivery, it could eliminate or at least diminish a lifetime of constant drug administration. The new imaging technique might add another $2,500 to such a procedure, but could also greatly improve the odds of its success, he said. The approach could also be applied to regenerative procedures in other organs, such as the liver.

Stanford has filed for provisional patents on intellectual property associated with this research. The study was funded by National Cancer Institute grants (U54CA119367 and P50CA114747). Another co-author was Christine Khademi, an undergraduate working in Gambhir's lab who has since graduated from Stanford.

###

Information about the medical school's Department of Radiology, which also supported the work, is available at http://radiology.stanford.edu/.

The Stanford University School of Medicine consistently ranks among the nation's top medical schools, integrating research, medical education, patient care and community service. For more news about the school, please visit http://mednews.stanford.edu. The medical school is part of Stanford Medicine, which includes Stanford Hospital & Clinics and Lucile Packard Children's Hospital. For information about all three, please visit http://stanfordmedicine.org/about/news.html.

Print media contact: Bruce Goldman at (650) 725-2106 (goldmanb@stanford.edu)

Broadcast media contact: M.A. Malone at (650) 723-6912 (mamalone@stanford.edu)

END