(Press-News.org) When babies are deprived of oxygen before birth, brain damage and disorders such as cerebral palsy can occur. Extended cooling can prevent brain injuries, but this treatment is not always available in developing nations where advanced medical care is scarce. To address this need, Johns Hopkins undergraduates have devised a low-tech $40 unit to provide protective cooling in the absence of modern hospital equipment that can cost $12,000.

The device, called the Cooling Cure, aims to lower a newborn's temperature by about 6 degrees F for three days, a treatment that has been shown to protect the child from brain damage if administered shortly after a loss of oxygen has occurred. Common causes of this deficiency are knotting of the umbilical cord or a problem with the mother's placenta during a difficult birth. In developing regions, untrained delivery, anemia and malnutrition during pregnancy can also contribute to oxygen deprivation.

In a recent issue of the journal Medical Devices: Evidence and Research, the biomedical engineering student inventors and their medical advisors reported successful animal testing of the Cooling Cure prototype. The device is made of a clay pot, a plastic-lined burlap basket, sand, instant ice-pack powder, temperature sensors, a microprocessor and two AAA batteries. To activate it, just add water.

The device could help curtail a serious health problem called hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, which is triggered by oxygen deficiency in the brain. Globally, more than half of the newborns with a severe form of this condition die, and many of the survivors are diagnosed with cerebral palsy or other brain disorders. The problem is particularly acute in impoverished regions where pregnant women do not have easy access to medical specialists or high-tech hospital equipment. The inventors say Cooling Cure could address this issue.

"The students came up with a neat device that's easy for non-medical people to use. It's inexpensive and user-friendly," said Michael V. Johnston, a Johns Hopkins School of Medicine pediatric neurology professor who advised the undergraduate team. Johnston also is chief medical officer and executive vice president of the Kennedy Krieger Institute, an internationally recognized center in Baltimore that helps children and adolescents with disorders of the brain, spinal cord and musculoskeletal systems.

For the past 25 years, Johnston has been studying ways to protect a newborn's brain, including the use of costly hospital cooling units that keep brain cells from dying after an oxygen deficiency. Several years ago, while visiting Egypt, he learned that local doctors were using window fans or chilled water bottles in an inadequate effort to treat oxygen-deprived babies. When he returned to Baltimore, Johnston and Ryan Lee, a pediatric neurologist and postdoctoral fellow at Kennedy Krieger, discussed the problem with Robert Allen, a Johns Hopkins associate research professor in a biomedical engineering program that requires undergraduates to design and build devices to solve pressing medical problems. Allen suggested that Johnston and Lee present the baby-cooling dilemma to biomedical engineering students in the school's Center for Bioengineering Innovation and Design.

The challenge was accepted in 2011 by a team of Whiting School of Engineering undergraduates. With an eye toward simplicity and low cost, the students designed a cooler made of a clay pot and a plastic-lined basket, separated by a layer of sand and urea-based powder. This powder is the type used in instant cold-packs that help reduce swelling. To activate the baby-cooling unit, water is added to the mixture of sand and powder, causing a chemical reaction that draws heat away from the upper basket, which cradles the child. (The chemical would not come into direct contact with the newborn.)

The unit's batteries power a microprocessor and sensors that track the child's internal and skin temperatures. Small lights flash red if the baby's temperature is too hot, green if the temperature is correct and blue if the child is too cold. By viewing the lights, the baby's nurse or a family member could add water to the sand to increase cooling. If the child is too cool, the caregiver could lift the child away from the chilling surface until the proper temperature is restored.

Last May, at a student invention showcase organized by the university's Department of Biomedical Engineering, the Cooling Cure team presented its prototype, designed for a full-term newborn weighing up to 9 pounds and measuring up to 18 inches in length. The team won the Linda Trinh Memorial Award, which recognized Cooling Cure as an innovative global health project. In August, two of the student inventors were chosen to visit medical centers in India for a two-week trip sponsored by a group called Medical and Educational Perspectives. The group has also offered modest financial support to advance the Cooling Cure design project.

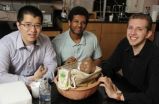

In recent months, three of the Cooling Cure's student inventors -- John J. Kim, Nathan Buchbinder and Simon Ammanual -- have opted to move the project forward through animal testing and improvement of the prototype.

"We've tried to continue this because we've gotten such good feedback from people," said Kim, of Santa Barbara, Calif., a leader of the student team who completed his undergraduate studies in December. "This is a nonprofit project. The main thing we want to do is to make sure that people in developing countries can benefit from this device."

Fellow team member Buchbinder, a sophomore from Marlboro, N.J., added, "It's not every day that you get to work on a medical device that could save lives and prevent disabilities in kids."

Working with the Johns Hopkins Technology Transfer staff, the students and their faculty advisors have obtained a provisional patent covering the low-cost baby-cooling unit. In the near future, the student inventors hope to link up with an international medical aid group and begin human clinical trials in a developing region.

INFORMATION:

John Kim was lead author of the Medical Devices: Evidence and Research study. The co-authors -- all Johns Hopkins student inventors and faculty advisors -- were Buchbinder, Ammanual, Robert Kim, Erika Moore, Neil O'Donnell, Jennifer K. Lee, Ewa Kulikowicz, Soumyadipta Acharya, Robert H. Allen, Ryan W. Lee and Michael V. Johnston. The article can be viewed at http://www.dovepress.com/articles.php?article_id=11849

Related links:

Johns Hopkins Center for Bioengineering Innovation and Design:

http://cbid.bme.jhu.edu/

Department of Biomedical Engineering: http://www.bme.jhu.edu/

Whiting School of Engineering: http://engineering.jhu.edu

Johns Hopkins Technology Transfer: http://techtransfer.jhu.edu/

Kennedy Krieger Institute: http://www.kennedykrieger.org/

Medical and Educational Perspectives: http://www.mepjhu.com/mep/mep.html

Video about this project here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7yeBEpBq8Ow

Low-cost 'cooling cure' would avert brain damage in oxygen-starved babies

2013-03-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

UF fossil bird study on extinction patterns could help today's conservation efforts

2013-03-22

GAINESVILLE, Fla. — A new University of Florida study of nearly 5,000 Haiti bird fossils shows contrary to a commonly held theory, human arrival 6,000 years ago didn't cause the island's birds to die simultaneously.

Although many birds perished or became displaced during a mass extinction event following the first arrival of humans to the Caribbean islands, fossil evidence shows some species were more resilient than others. The research provides range and dispersal patterns from A.D. 600 to 1600 that may be used to create conservation plans for tropical mountainous regions, ...

Scientists reveal quirky feature of Lyme disease bacteria

2013-03-22

Scientists have confirmed that the pathogen that causes Lyme Disease—unlike any other known organism—can exist without iron, a metal that all other life needs to make proteins and enzymes. Instead of iron, the bacteria substitute manganese to make an essential enzyme, thus eluding immune system defenses that protect the body by starving pathogens of iron.

To cause disease, Borrelia burgdorferi requires unusually high levels of manganese, scientists at Johns Hopkins University (JHU), Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), and the University of Texas reported. Their ...

New ASTRO white paper recommends peer review to increase quality assurance and safety

2013-03-22

The American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) has issued a new white paper, "Enhancing the role of case-oriented peer review to improve quality and safety in radiation oncology: Executive Summary," that recommends increased peer review within the radiation therapy treatment process and among members of the radiation oncology team in order to increase quality assurance and safety, according to the manuscript published as an article in press online in Practical Radiation Oncology (PRO), the official clinical practice journal of ASTRO. The executive summary and supplemental ...

Prescription for double-dose algebra proves effective

2013-03-22

Martin Gartzman sat in his dentist's waiting room last fall when he read a study in Education Next that nearly brought him to tears.

A decade ago, in his former position as chief math and science officer for Chicago Public Schools, Gartzman spearheaded an attempt to decrease ninth-grade algebra failure rates, an issue he calls "an incredibly vexing problem." His idea was to provide extra time for struggling students by having them take two consecutive periods of algebra.

Gartzman had been under the impression that the double-dose algebra program he had instituted had ...

Research explores links between physical and emotional pain relief

2013-03-22

Though we all desire relief -- from stress, work, or pain -- little is known about the specific emotions underlying relief. New research from the Association for Psychological Science explores the psychological mechanisms associated with relief that occurs after the removal of pain, also known as pain offset relief.

This new research shows that healthy individuals and individuals with a history of self-harm display similar levels of relief when pain is removed, which suggests that pain offset relief may be a natural mechanism that helps us to regulate our emotions.

Feeling ...

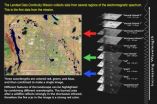

A closer look at LDCM's first scene

2013-03-22

Turning on new satellite instruments is like opening new eyes. This week, the Landsat Data Continuity Mission (LDCM) released its first images of Earth, collected at 1:40 p.m. EDT on March 18. The first image shows the meeting of the Great Plains with the Front Ranges of the Rocky Mountains in Wyoming and Colorado. The natural-color image shows the green coniferous forest of the mountains coming down to the dormant brown plains. The cities of Cheyenne, Fort Collins, Loveland, Longmont, Boulder and Denver string out from north to south. Popcorn clouds dot the plains while ...

Stayin' alive -- delivering resuscitation messages to the public

2013-03-22

Teaching bystander Cardiac Pulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) strategically to the general public offers the greatest potential to make the biggest overall impact on survival in out of hospital cardiac arrests in Europe, reported a main session on Resuscitation Science at the European Society of Cardiology's EuroHeart Care Congress, which took place in Glasgow, 22 to 23 March, 2013.

"The reality is that four out of five cardiac arrests happen at home, and unless the public are trained in resuscitation many people die before emergency services get to them," said Mary Hannon. ...

Complementary and alternative medicine studies take center stage at EuroHeart Care

2013-03-22

Yoga and acupressure could both play an important role in helping patients with atrial fibrillation (AF). Two abstracts presented at the at the European Society of Cardiology's EuroHeart Care Congress, which takes place in Glasgow, 22 to 23 March, 2013, show the potential for medical yoga¹ and acupressure², in addition to pharmacological therapies, to reduce blood pressure and heart rates in patients with AF. In a third abstract³, a survey found that complementary and alternative therapies (CATs), were widely used by patients attending cardiology clinics, raising concerns ...

Prevention of heart disease requires professionals to go out into communities

2013-03-22

Deprivation represents the "elephant in the room" with regard to cardiovascular disease (CVD), and health care professionals have an important role to play in tackling the problem, delegates heard at a special plenary session opening the EuroHeart Care Congress in Glasgow, Scotland, 22 March to 23 March 2013. The session heard how Scotland, a country considered to have the highest rates of heart disease in Western Europe, has recently taken action to address the CVD health inequalities that exist between affluent and deprived communities.

Mr Michael Matheson, the Public ...

Smoking affects fracture healing

2013-03-22

CHICAGO – In a new study presented today at the 2013 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS), researchers reviewed existing literature on smoking and the healing of fractures involving long bones (bones that are longer than they are wide).

The analysis of data from 20 studies found an overall 2.3 times higher risk of nonunion (bones that do not heal properly) in smokers. Similarly, for all fractures, the average time to fracture healing was longer for smokers (32 weeks) than nonsmokers (25.1 weeks).

The review illustrates the effects ...