(Press-News.org) PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — A key advance, newly reported by chemists from Brown and Yale Universities, could lead to a cheaper and more sustainable way to make acrylate, an important commodity chemical used to make materials from polyester fabrics to diapers.

Chemical companies churn out billions of tons of acrylate each year, usually by heating propylene, a compound derived from crude oil. "What we're interested in is enhancing both the economics and the sustainability of how acrylate is made," said Wesley Bernskoetter, assistant professor of chemistry at Brown, who led the research. "Right now, everything that goes into making it is from relatively expensive, nonrenewable carbon sources."

Since the 1980s researchers have been looking into the possibility of making acrylate by combining carbon dioxide with a gas called ethylene in the presence of nickel and other metal catalysts. CO2 is essentially free and something the planet currently has in overabundance. Ethylene is cheaper than propylene and can be made from plant biomass.

There has been a persistent obstacle to the approach, however. Instead of forming the acrylate molecule, CO2 and ethylene tend to form a precursor molecule with a five-membered ring made of oxygen, nickel, and three carbon atoms. In order to finish the conversion to acrylate, that ring needs to be cracked open to allow the formation of a carbon-carbon double bond, a process called elimination.

That step had proved elusive. But the research by Bernskoetter and his colleagues, published in the journal Organometallics, shows that a class of chemicals called Lewis acids can easily break open that five-membered ring, allowing the molecule to eliminate and form acrylate.

Lewis acids are basically electron acceptors. In this case, the acid steals away electrons that make up the bond between nickel and oxygen in the ring. That weakens the bond and opens the ring.

"We thought that if we could find a way to cut the ring chemically, then we would be able to eliminate very quickly and form acrylate," Bernskoetter said. "And that turns out to be true."

He calls the finding an "enabling technology" that could eventually be incorporated in a full catalytic process for making acrylate on a mass scale. "We can now basically do all the steps required," he said.

From here, the team needs to tweak the strength of the Lewis acid used. To prove the concept, they used the strongest acid that was easily available, one derived from boron. But that acid is too strong to use in a repeatable catalytic process because it bonds too strongly to the acrylate product to allow additional reactions with the nickel catalyst.

"In developing and testing the idea, we hit it with the biggest hammer we could," Bernskoetter said. "So what we have to do now is dial back and find one that makes it more practical."

There's quite a spectrum of Lewis acid strengths, so Bernskoetter is confident that there's one that will work. "We think it's possible," he said. "Organic chemists do this kind of reaction with Lewis acids all the time."

The ongoing research is part of a collaboration between Brown and Yale supported by the National Science Foundation's Centers for Chemical Innovation program. The work is aimed at activating CO2 for use in making all kinds of commodity chemicals, and acrylate is a good place to start.

"It's around a $2 billion-a-year industry," Bernskoetter said. "If we can find a way to make acrylate more cheaply, we think the industry will be interested."

INFORMATION:

Other authors on the paper were Dong Jin and Paul Willard of Brown and Nilay Hazari and Timothy Schmeier of Yale.

Editors: Brown University has a fiber link television studio available for domestic and international live and taped interviews, and maintains an ISDN line for radio interviews. For more information, call (401) 863-2476.

END

When babies are deprived of oxygen before birth, brain damage and disorders such as cerebral palsy can occur. Extended cooling can prevent brain injuries, but this treatment is not always available in developing nations where advanced medical care is scarce. To address this need, Johns Hopkins undergraduates have devised a low-tech $40 unit to provide protective cooling in the absence of modern hospital equipment that can cost $12,000.

The device, called the Cooling Cure, aims to lower a newborn's temperature by about 6 degrees F for three days, a treatment that has been ...

GAINESVILLE, Fla. — A new University of Florida study of nearly 5,000 Haiti bird fossils shows contrary to a commonly held theory, human arrival 6,000 years ago didn't cause the island's birds to die simultaneously.

Although many birds perished or became displaced during a mass extinction event following the first arrival of humans to the Caribbean islands, fossil evidence shows some species were more resilient than others. The research provides range and dispersal patterns from A.D. 600 to 1600 that may be used to create conservation plans for tropical mountainous regions, ...

Scientists have confirmed that the pathogen that causes Lyme Disease—unlike any other known organism—can exist without iron, a metal that all other life needs to make proteins and enzymes. Instead of iron, the bacteria substitute manganese to make an essential enzyme, thus eluding immune system defenses that protect the body by starving pathogens of iron.

To cause disease, Borrelia burgdorferi requires unusually high levels of manganese, scientists at Johns Hopkins University (JHU), Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), and the University of Texas reported. Their ...

The American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) has issued a new white paper, "Enhancing the role of case-oriented peer review to improve quality and safety in radiation oncology: Executive Summary," that recommends increased peer review within the radiation therapy treatment process and among members of the radiation oncology team in order to increase quality assurance and safety, according to the manuscript published as an article in press online in Practical Radiation Oncology (PRO), the official clinical practice journal of ASTRO. The executive summary and supplemental ...

Martin Gartzman sat in his dentist's waiting room last fall when he read a study in Education Next that nearly brought him to tears.

A decade ago, in his former position as chief math and science officer for Chicago Public Schools, Gartzman spearheaded an attempt to decrease ninth-grade algebra failure rates, an issue he calls "an incredibly vexing problem." His idea was to provide extra time for struggling students by having them take two consecutive periods of algebra.

Gartzman had been under the impression that the double-dose algebra program he had instituted had ...

Though we all desire relief -- from stress, work, or pain -- little is known about the specific emotions underlying relief. New research from the Association for Psychological Science explores the psychological mechanisms associated with relief that occurs after the removal of pain, also known as pain offset relief.

This new research shows that healthy individuals and individuals with a history of self-harm display similar levels of relief when pain is removed, which suggests that pain offset relief may be a natural mechanism that helps us to regulate our emotions.

Feeling ...

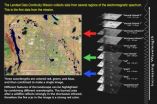

Turning on new satellite instruments is like opening new eyes. This week, the Landsat Data Continuity Mission (LDCM) released its first images of Earth, collected at 1:40 p.m. EDT on March 18. The first image shows the meeting of the Great Plains with the Front Ranges of the Rocky Mountains in Wyoming and Colorado. The natural-color image shows the green coniferous forest of the mountains coming down to the dormant brown plains. The cities of Cheyenne, Fort Collins, Loveland, Longmont, Boulder and Denver string out from north to south. Popcorn clouds dot the plains while ...

Teaching bystander Cardiac Pulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) strategically to the general public offers the greatest potential to make the biggest overall impact on survival in out of hospital cardiac arrests in Europe, reported a main session on Resuscitation Science at the European Society of Cardiology's EuroHeart Care Congress, which took place in Glasgow, 22 to 23 March, 2013.

"The reality is that four out of five cardiac arrests happen at home, and unless the public are trained in resuscitation many people die before emergency services get to them," said Mary Hannon. ...

Yoga and acupressure could both play an important role in helping patients with atrial fibrillation (AF). Two abstracts presented at the at the European Society of Cardiology's EuroHeart Care Congress, which takes place in Glasgow, 22 to 23 March, 2013, show the potential for medical yoga¹ and acupressure², in addition to pharmacological therapies, to reduce blood pressure and heart rates in patients with AF. In a third abstract³, a survey found that complementary and alternative therapies (CATs), were widely used by patients attending cardiology clinics, raising concerns ...

Deprivation represents the "elephant in the room" with regard to cardiovascular disease (CVD), and health care professionals have an important role to play in tackling the problem, delegates heard at a special plenary session opening the EuroHeart Care Congress in Glasgow, Scotland, 22 March to 23 March 2013. The session heard how Scotland, a country considered to have the highest rates of heart disease in Western Europe, has recently taken action to address the CVD health inequalities that exist between affluent and deprived communities.

Mr Michael Matheson, the Public ...