(Press-News.org) By André Julião | Agência FAPESP - The black lion tamarin (Leontopithecus chrysopygus) once inhabited most forest areas in the state of São Paulo, Southeast Brazil, but currently occupies only some Atlantic Rainforest remnants there. In recent years, after various studies of the endangered species, environmental NGO Instituto de Pesquisas Ecológicas (IPÊ) moved groups of these animals to areas from which the species had disappeared.

Similar initiatives have now been reinforced by a group of researchers at IPÊ, São Paulo State University (UNESP) and the Federal University of Mato Grosso (UFMT), who cross-tabulated climate data and data on landscape (forest cover) to determine the sites best suited for future translocation, a technique used by conservationists to bolster the viability and gene flow of endangered species.

The study was supported by FAPESP and published in the American Journal of Primatology.

"We used climate and landscape data to try to predict which areas within the original distribution of the species are suitable for its conservation. The most widely used models use only climate data. Our study innovated by combining these two datasets in an approach that enabled us to identify the areas that are theoretically most suitable and compare them with the areas in which the species actually lives now," said Laurence Culot, a professor at UNESP's Institute of Biosciences (IB) in Rio Claro and principal investigator for the project "The effect of fragmentation on the ecological functions of primates", which was funded by FAPESP and gave rise to the study.

The first author of the published paper on the study is Gabriela Cabral Rezende, who conducted it as part of her PhD research at IB-UNESP with a scholarship from FAPESP.

The black lion tamarin originally inhabited a long strip of the state of São Paulo running through its southwestern and central portions and amounting in aggregate to 92,239 square kilometers (km²). The model created by the researchers pointed to only 2,096 km² of suitable areas for the species, currently found in less than 40%. In sum, the species now occupies less than 1% of its original distribution area.

"The numbers are alarming," Rezende said. "However, at the same time, they show there are suitable areas not currently inhabited by the species. We used this information to design better targeted strategies."

Forest restoration

To determine which areas would be most suitable for the species, the researchers used a methodology that correlated data for the locations in which it lives now with climate and landscape data for the area it originally occupied. The model pinpointed more areas that would be suitable in terms of climate than landscape, such as Pontal do Paranapanema in the southwest of the state and Upper Paranapanema in southeastern São Paulo.

"These areas should be prioritized for forest restoration, connecting the forest remnants inhabited by the species and benefiting other animals," Culot said.

Areas that would be suitable in terms of both climate and landscape rank highest on the list of translocation priorities. Groups moved to these areas would be far more likely to be ecologically and genetically healthy in the medium to long run than those translocated elsewhere. Some areas in the southwest and southeast of the state matched these criteria and are therefore considered the top priority for conservation of the species.

The researchers also stress the need to identify suitable areas in light of the climate change scenarios projected for the coming decades. According to a study by a different group, an area south of the Serra de Paranapiacaba (Paranapiacaba ridge, which is already inhabited by black lion tamarins) will undergo change that will make its climate more suitable for conservation of the species in the next 30-60 years. This is a large forest and considered highly suitable in landscape terms by Rezende et al., with major potential to serve as a habitat for populations of black lion tamarins in future, assuring their viability.

The species is known to be ecologically plastic and should be able to adapt to climate and landscape change, although to what extent this will affect its physiology is hard to know exactly. Its diet can shift toward fruit or small vertebrates, depending on availability. It can travel about 180 meters on the ground between forest fragments, although this incurs risks such as roadkill, predation, and attacks from domestic animals. It also plays an important role in forest regeneration by dispersing seeds.

For the researchers, it is particularly urgent to be as cost-effective as possible at a time in which resources for species conservation are increasingly scarce - hence the importance of prioritizing areas and implementing properly targeted strategies.

"The study shows how theoretical models can be used in practice to help plan conservation policies and actions, increasing the likelihood of success," Rezende said. "Although it focuses on a single species, the approach it describes is a powerful tool that can be used to establish conservation priorities for other species."

INFORMATION:

About São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP)

The São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) is a public institution with the mission of supporting scientific research in all fields of knowledge by awarding scholarships, fellowships and grants to investigators linked with higher education and research institutions in the State of São Paulo, Brazil. FAPESP is aware that the very best research can only be done by working with the best researchers internationally. Therefore, it has established partnerships with funding agencies, higher education, private companies, and research organizations in other countries known for the quality of their research and has been encouraging scientists funded by its grants to further develop their international collaboration. You can learn more about FAPESP at http://www.fapesp.br/en and visit FAPESP news agency at http://www.agencia.fapesp.br/en to keep updated with the latest scientific breakthroughs FAPESP helps achieve through its many programs, awards and research centers. You may also subscribe to FAPESP news agency at http://agencia.fapesp.br/subscribe.

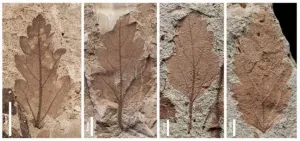

The asteroid impact 66 million years ago that ushered in a mass extinction and ended the dinosaurs also killed off many of the plants that they relied on for food. Fossil leaf assemblages from Patagonia, Argentina, suggest that vegetation in South America suffered great losses but rebounded quickly, according to an international team of researchers.

"Every mass extinction event is like a reset button, and what happens after that reset depends on which organisms survive and how they shape the biosphere," said Elena Stiles, a doctoral student at the University of Washington who completed the research as part of her master's thesis at Penn State. "All the biodiversity ...

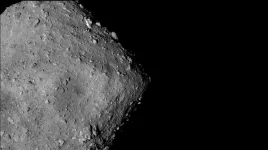

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- Last month, Japan's Hayabusa2 mission brought home a cache of rocks collected from a near-Earth asteroid called Ryugu. While analysis of those returned samples is just getting underway, researchers are using data from the spacecraft's other instruments to reveal new details about the asteroid's past.

In a study published in Nature Astronomy, researchers offer an explanation for why Ryugu isn't quite as rich in water-bearing minerals as some other asteroids. The study suggests that the ancient parent body from which Ryugu was formed had likely dried out in some kind of heating event before Ryugu came into being, which left Ryugu itself drier than expected.

"One of the ...

Repeated intravenous (IV) ketamine infusions significantly reduce symptom severity in individuals with chronic post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and the improvement is rapid and maintained for several weeks afterwards, according to a study conducted by researchers from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. The study, published September XX in the American Journal of Psychiatry, is the first randomized, controlled trial of repeated ketamine administration for chronic PTSD and suggests this may be a promising treatment for PTSD patients.

"Our findings provide insight into the treatment efficacy of repeated ketamine ...

As the world grows increasingly globalized, one of the ways that countries have come to rely on one another is through a more intricate and interconnected food supply chain. Food produced in one country is often consumed in another country -- with technological advances allowing food to be shipped between countries that are increasingly distant from one another.

This interconnectedness has its benefits. For instance, if the United States imports food from multiple countries and one of those countries abruptly stops exporting food to the United States, there are still other countries that can be relied on ...

SAN ANTONIO and CHICAGO - An article published Jan. 5 in Alzheimer's & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer's Association cites decades of published scientific evidence to make a compelling case for SARS-CoV-2's expected long-term effects on the brain and nervous system.

Dementia researchers from The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UT Health San Antonio) are the first and senior authors of the report and are joined by coauthors from the Alzheimer's Association and Nottingham and Leicester universities in England.

"Since the flu pandemic of 1917 and 1918, many of the flulike diseases have been associated with brain disorders," said lead author ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- Self-control, the ability to contain one's own thoughts, feelings and behaviors, and to work toward goals with a plan, is one of the personality traits that makes a child ready for school. And, it turns out, ready for life as well.

In a large study that has tracked a thousand people from birth through age 45 in New Zealand, researchers have determined that people who had higher levels of self-control as children were aging more slowly than their peers at age 45. Their bodies and brains were healthier and biologically younger.

In interviews, the higher self-control group also showed they may be better equipped to handle the health, financial and social challenges of later life as well. The researchers used structured interviews and credit checks ...

NEW YORK, NY (1/5/2021) - Subtle changes in speech and language can be an early warning sign of Alzheimer's -- sometimes appearing long before other more serious symptoms. The challenge is recognizing these changes and determining what may signal Alzheimer's or other neurodegenerative disorders. In a commentary in END ...

One sweaty, huffing, exercising person emits as many chemicals from their body as up to five sedentary people, according to a new University of Colorado Boulder study. And notably, those human emissions, including amino acids from sweat or acetone from breath, chemically combine with bleach cleaners to form new airborne chemicals with unknown impacts to indoor air quality.

"Humans are a large source of indoor emissions," said Zachary Finewax, CIRES research scientist and lead author of the new study out in the current edition of Indoor Air. "And chemicals in indoor air, whether from our bodies or cleaning products, don't just disappear, they linger and travel around spaces like gyms, reacting with other chemicals."

In 2018, the CU Boulder ...

Heating up cancer cells while targeting them with chemotherapy is a highly effective way of killing them, according to a new study led by UCL researchers.

The study, published in the Journal of Materials Chemistry B, found that "loading" a chemotherapy drug on to tiny magnetic particles that can heat up the cancer cells at the same time as delivering the drug to them was up to 34% more effective at destroying the cancer cells than the chemotherapy drug without added heat.

The magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles that carry the chemotherapy drug shed heat when exposed to an alternating magnetic field. This means that, once the nanoparticles have accumulated in the tumour area, an alternating magnetic field can be applied from outside the ...

Researchers in Japan have made the first observations of biological magnetoreception - live, unaltered cells responding to a magnetic field in real time. This discovery is a crucial step in understanding how animals from birds to butterflies navigate using Earth's magnetic field and addressing the question of whether weak electromagnetic fields in our environment might affect human health.

"The joyous thing about this research is to see that the relationship between the spins of two individual electrons can have a major effect on biology," said Professor Jonathan Woodward from the University of Tokyo, who conducted the research with doctoral ...