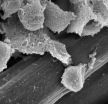

(Press-News.org) By combining a synthetic scaffolding material with gene delivery techniques, researchers at Duke University are getting closer to being able to generate replacement cartilage where it's needed in the body.

Performing tissue repair with stem cells typically requires applying copious amounts of growth factor proteins -- a task that is very expensive and becomes challenging once the developing material is implanted within a body. In a new study, however, Duke researchers found a way around this limitation by genetically altering the stem cells to make the necessary growth factors all on their own.

They incorporated viruses used to deliver gene therapy to the stem cells into a synthetic material that serves as a template for tissue growth. The resulting material is like a computer; the scaffold provides the hardware and the virus provides the software that programs the stem cells to produce the desired tissue.

The study appears online the week of Feb. 17 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Farshid Guilak, director of orthopaedic research at Duke University Medical Center, has spent years developing biodegradable synthetic scaffolding that mimics the mechanical properties of cartilage. One challenge he and all biomedical researchers face is getting stem cells to form cartilage within and around the scaffolding, especially after it is implanted into a living being.

The traditional approach has been to introduce growth factor proteins, which signal the stem cells to differentiate into cartilage. Once the process is under way, the growing cartilage can be implanted where needed.

"But a major limitation in engineering tissue replacements has been the difficulty in delivering growth factors to the stem cells once they are implanted in the body," said Guilak, who is also a professor in Duke's Department of Biomedical Engineering. "There's a limited amount of growth factor that you can put into the scaffolding, and once it's released, it's all gone. We need a method for long-term delivery of growth factors, and that's where the gene therapy comes in."

For ideas on how to solve this problem, Guilak turned to his colleague Charles Gersbach, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering and an expert in gene therapy. Gersbach proposed introducing new genes into the stem cells so that they produce the necessary growth factors themselves.

But the conventional methods for gene therapy are complex and difficult to translate into a strategy that would be feasible as a commercial product.

This type of gene therapy generally requires gathering stem cells, modifying them with a virus that transfers the new genes, culturing the resulting genetically altered stem cells until they reach a critical mass, applying them to the synthetic cartilage scaffolding and, finally, implanting it into the body.

"There are a few challenges with that process, one of them being that there are way too many extra steps," said Gersbach. "So we turned to a technique I had previously developed that affixes the viruses that deliver the new genes onto a material's surface."

The new study uses Gersbach's technique -- dubbed biomaterial-mediated gene delivery -- to induce the stem cells placed on Guilak's synthetic cartilage scaffolding to produce growth factor proteins. The results show that the technique works and that the resulting composite material is at least as good biochemically and biomechanically as if the growth factors were introduced in the laboratory.

"We want the new cartilage to form in and around the synthetic scaffold at a rate that can match or exceed the scaffold's degradation," said Jonathan Brunger, a graduate student who has spent time in both Guilak's and Gersbach's laboratories developing and testing the new technique. "So while the stem cells are making new tissue (in the body), the scaffold can withstand the load of the joint. In the ideal case, one would eventually end up with a viable cartilage tissue substitute replacing the synthetic material."

While this study focuses on cartilage regeneration, Guilak and Gersbach say that the technique could be applied to many kinds of tissues, especially orthopaedic tissues such as tendons, ligaments and bones. And because the platform comes ready to use with any stem cell, it presents an important step toward commercialization.

"One of the advantages of our method is getting rid of the growth factor delivery, which is expensive and unstable, and replacing it with scaffolding functionalized with the viral gene carrier," said Gersbach. "The virus-laden scaffolding could be mass-produced and just sitting in a clinic ready to go. We hope this gets us one step closer to a translatable product."

INFORMATION:

This work was supported in part by the Nancy Taylor Foundation for Chronic Diseases, the Arthritis Foundation, the AO Foundation, the National Science Foundation (CAREER Award CBET-1151035) and the National Institutes of Health (AR061042, AR50245, AR48852, AG15768, AR48182, AG46927 and OD008586).

CITATION: "Scaffold-mediated lentiviral transduction for functional tissue engineering of cartilage." Brunger, J.M., Huynh, N.P.T., Guenther, C.M., Perez-Pinera, P., Moutos, F.T., Sanchez-Adams, J., Gersbach C.A., and Guilak F. PNAS Plus, 2014. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1321744111/-/DCSupplemental

Regenerating orthopedic tissues within the human body

Duke researchers use gene therapy to direct stem cells into becoming new cartilage on a synthetic scaffold even after implantation into a living body

2014-02-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Research of zebrafish neurons may lead to understanding of birth defects like spina bifida

2014-02-18

COLUMBIA, Mo. – The zebrafish, a tropical freshwater fish similar to a minnow and native to the southeastern Himalayan region, is well established as a key tool for researchers studying human diseases, including brain disorders. Using zebrafish, scientists can determine how individual neurons develop, mature and support basic functions like breathing, swallowing and jaw movement. Researchers at the University of Missouri say that learning about neuronal development and maturation in zebrafish could lead to a better understanding of birth defects such as spina bifida in ...

Prison-based education declined during economic downturn, study finds

2014-02-18

State-level spending on prison education programs declined sharply during the economic downturn, with the sharpest drop occurring in states that incarcerate the most prisoners, according to a new RAND Corporation study.

Large states cut spending by an average of 10 percent between the 2009 and 2012 fiscal years, while medium-sized states cut spending by 20 percent, according to the study.

"There has been a dramatic contraction of the prison education system, particularly those programs focused on academic instruction versus vocational training," said Lois Davis, the ...

Miriam Hospital study shows social gaming site effective weight loss tool

2014-02-18

(PROVIDENCE, R.I.) -- Researchers from The Miriam Hospital have found that DietBet, a web-based commercial weight loss program that pairs financial incentives with social influence, delivers significant weight losses. The study and its findings have been published in the current issue of the open access publication JMIR Serious Games.

Tricia Leahey, Ph.D., lead researcher at The Miriam Hospital Weight Control and Diabetes Research Center, sought to examine weight losses associated with the social gaming website and contributing factors to gauge the success of such web-based ...

Rife with hype, exoplanet study needs patience and refinement

2014-02-18

Imagine someone spent months researching new cities to call home using low-resolution images of unidentified skylines. The pictures were taken from several miles away with a camera intended for portraits, and at sunset. From these fuzzy snapshots, that person claims to know the city's air quality, the appearance of its buildings, and how often it rains.

This technique is similar to how scientists often characterize the atmosphere — including the presence of water and oxygen — of planets outside of Earth's solar system, known as exoplanets, according to a review of exoplanet ...

Frequent flyers, bottle gourds crossed the ocean many times

2014-02-18

Bottle gourds traveled the Atlantic Ocean from Africa and were likely domesticated many times in various parts of the New World, according to a team of scientists who studied bottle gourd genetics to show they have an African, not Asian ancestry.

"Beginning in the 1950s we thought that bottle gourds floated across the ocean from Africa," said Logan Kistler, post-doctoral researcher in anthropology, Penn State. "However, a 2005 genetic study of gourds suggested an Asian origin."

Domesticated bottle gourds are ubiquitous around the world in tropical and temperate areas ...

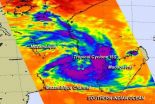

NASA sees Tropical Cyclone 15S form in the Mozambique Channel

2014-02-18

NASA's Aqua satellite passed over Tropical Cyclone 15S as it formed in the Mozambique Channel on Feb. 18 and the AIRS instrument aboard gathered infrared data on its cloud top temperatures and potential.

NASA's Aqua satellite passed over Tropical cyclone 15S on Feb. 18 at 10:53 a.m. EST. The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder or AIRS instrument captured infrared data on the tropical system that showed the highest cloud tops and strongest thunderstorms were in a band that stretched from the east to the south of the center. Cloud top temperatures were near -63F/-52C, indicating ...

Agricultural productivity loss as a result of soil and crop damage from flooding

2014-02-18

URBANA, Ill. – The Cache River Basin, which once drained more than 614,100 acres across six southern Illinois counties, has changed substantively since the ancient Ohio River receded. The basin contains a slow-moving, meandering river; fertile soils and productive farmlands; deep sand and gravel deposits; sloughs and uplands; and one of the most unique and diverse natural habitats in Illinois and the nation.

According to a recent University of Illinois study, the region's agricultural lands dodged a bullet due to the timing of the great flood of April 2011 when the Ohio ...

GW spirituality and health pioneer publishes paper on development of the field

2014-02-18

WASHINGTON (Feb. 18, 2014) — While spirituality played a significant role in health care for centuries, technological advances in the 20th century overshadowed this more human side of medicine. Christina Puchalski, M.D.'94, RESD'97, founder and director of the George Washington University (GW) Institute for Spirituality and Health and professor of medicine at the GW School of Medicine and Health Sciences (SMHS), and co-authors published a commentary in Academic Medicine on the history of spirituality and health, the movement to reclaim medicine's spiritual roots, and the ...

Neuropsychological assessment more efficient than MRI for tracking disease progression

2014-02-18

Amsterdam, NL, February 18, 2014 – Investigators at the University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands, have shown that progression of disease in memory clinic patients can be tracked efficiently with 45 minutes of neuropsychological testing. MRI measures of brain atrophy were shown to be less reliable to pick up changes in the same patients.

This finding has important implications for the design of clinical trials of new anti-Alzheimer drugs. If neuropsychological assessment is used as the outcome measure or "gold standard," fewer patients would be needed to conduct such ...

Artificial cells and salad dressing

2014-02-18

RIVERSIDE, Calif. (http://www.ucr.edu) — A University of California, Riverside assistant professor of engineering is among a group of researchers that have made important discoveries regarding the behavior of a synthetic molecular oscillator, which could serve as a timekeeping device to control artificial cells.

Elisa Franco, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at UC Riverside's Bourns College of Engineering, and the other researchers developed methods to screen thousands of copies of this oscillator using small droplets. They found, surprisingly, that the ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

[Press-News.org] Regenerating orthopedic tissues within the human bodyDuke researchers use gene therapy to direct stem cells into becoming new cartilage on a synthetic scaffold even after implantation into a living body