(Press-News.org) NASHVILLE, Tenn. – To develop correctly, baby hearts need rhythm...even before they have blood to pump.

"We have discovered that mechanical forces are important when making baby hearts," said Mary Kathryn Sewell-Loftin, a Vanderbilt graduate student working with a team of Vanderbilt engineers, scientists and clinicians attempting to grow replacement heart valves from a patient's own cells.

In an article published last month in the journal Biomaterials the team reported that they have taken an important step toward this goal by determining that the mechanical forces generated by the rhythmic expansion and contraction of cardiac muscle cells play an active role in the initial stage of heart valve formation.

A heart valve is a marvelous device. It consists of two or three flaps, called leaflets, which open and close to control the flow of blood through the heart. It is designed well enough to cycle two to three billion times in a person's lifetime. (Humans and chickens are outliers: Most other animals, large and small, have hearts that beat about one billion times in their lives.) However, heart valves can be damaged by diseases such as rheumatic fever and cancer, aging, heart attacks and birth defects.

"For the last 15 years, people have been trying to create a heart valve out of artificial tissue using brute-force engineering methods without any success," said Assistant Professor of Biomedical Engineering W. David Merryman. "We decided to take a step back and study how heart valves develop naturally so we can figure out how to duplicate the process." To do so, they designed a series of experiments with chickens, whose hearts develop in a fashion similar to the human heart.

"The discovery that the deformations produced by the beating cardiac muscle cells are important provides an entirely new perspective on the process," said Merryman, who directed the three-year study.

The Vanderbilt effort is part of a broader program to develop artificial organs named the Systems-based Consortium for Organ Design and Engineering (SysCODE). It is a National Institutes of Health "Roadmap" initiative to speed the movement of scientific discoveries from the bench to the bedside.

"This is the second major advance that we've made," said Professor of Pharmacology Joey Barnett, co-principal investigator of the heart valve project.

Last spring, the Vanderbilt team announced that they had identified the unique genes and molecular pathways associated with valve formation. "These included both genes and pathways that we knew about and several that were previously unknown," said Barnett, who has studied heart valves for more than 20 years.

"The genetic study gave us the list of the basic parts – the hardware – required to build a heart valve and this latest study provides us with the information we need about the environment that is required," said the biologist. "With this information, we should have what we need to create valvular interstitial cells (VICs), that are the basic building blocks of heart valves."

The heart starts out as a simple, U-shaped tube of tissue. (In the case of the chicken embryo, it is about the size of a comma on the printed page.) The tube has three layers. The outer layer is made up of cardiac muscle cells that begin pulsing before blood vessels form and attach to the heart. The inner layer consists of specialized endothelial cells, the type of cells that line the interior of blood vessels. Sandwiched between the two is a layer of a complex gelatinous material called cardiac jelly.

At the locations of the inflow and outflow valves, the walls of the tube thicken to form "cushions" of cardiac jelly. After the cushions are formed, the endothelial cells in the region embed themselves in the cushion and transform into VICs. The VICs, in turn, begin guiding the process that transforms the cardiac jelly in the cushion into valve leaflets.

One of the standard laboratory methods for studying the early stages of heart development is to use microsurgery to remove a chick heart from an embryo and place it in a cell-culture dish filled with collagen gel. However, the method was not suitable for studying mechanical forces so Sewell-Loftin had to modify it substantially. She found one key was to include a complex sugar called hyaluronic acid, which is found in cardiac jelly.

Next, she had to devise a method to measure the amount of deformation that the pulsation of the heart muscle cells causes in the gel. She did so by creating a computer program that analyzed sequences of microscope images of the gel surface to estimate the forces caused by the pulsing cells.

When Sewell-Loftin compared her maps with the locations where VICs were being formed, she found that cells were transforming preferentially in areas of high strain.

The team's next step is to collaborate with a researcher who works with induced pluripotent stem cells – a type of stem cell that can be generated directly from adult cells – to produce endothelial cells. Once they have these cells, they hope to produce human VICs. In addition to guiding the initial formation of the heart, VICs are known to play a role in maintaining valve health in adults. So they could provide a better way to repair calcified heart valves, the major cause of open-heart surgery in adults, the researchers speculate.

Once they can make human VICs, there is a good chance that they will create artificial human heart valves when they are placed in a properly designed bioreactor, the researchers anticipate. And once they have artificial human heart valves, they could be used to replace defective valves when needed in the 40,000 babies born with congenital heart defects each year. Hopefully, these artificial valves would grow with the child. Current replacement valves are made out of plastic so they do not grow with a child. That means these young patients must endure multiple surgeries, which multiplies their risk of harmful complications.

INFORMATION:

H. Scott Baldwin, the Katrina Overall McDonald Chair of Pediatrics, graduate student Daniel M. DeLaughter, undergraduate student Jon R. Peacock, and Christopher Brown, research assistant professor of pediatrics, contributed to the study.

The research was supported by grants from the American Heart Association, National Science Foundation grant 1055384 and National Institutes of Health grants HL094707 and HL092551. Tyson Foods, Inc. donated the fertilized chicken eggs used in the study.

Visit Research News @ Vanderbilt for more research news from Vanderbilt. [Media Note: Vanderbilt has a 24/7 TV and radio studio with a dedicated fiber optic line and ISDN line. Use of the TV studio with Vanderbilt experts is free, except for reserving fiber time.]

Baby hearts need rhythm to develop correctly

2014-02-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Nitrogen-tracking tools for better crops and less pollution

2014-02-18

Stanford, CA— As every gardner knows, nitrogen is crucial for a plant's growth. But nitrogen absorption is inefficient. This means that on the scale of food crops, adding significant levels of nitrogen to the soil through fertilizer presents a number of problems, particularly river and groundwater pollution. As a result, finding a way to improve nitrogen uptake in agricultural products could improve yields and decrease risks to environmental and human health. Nitrogen is primarily taken up from the soil by the roots and assimilated by the plant to become part of DNA, ...

Regenerating orthopedic tissues within the human body

2014-02-18

By combining a synthetic scaffolding material with gene delivery techniques, researchers at Duke University are getting closer to being able to generate replacement cartilage where it's needed in the body.

Performing tissue repair with stem cells typically requires applying copious amounts of growth factor proteins -- a task that is very expensive and becomes challenging once the developing material is implanted within a body. In a new study, however, Duke researchers found a way around this limitation by genetically altering the stem cells to make the necessary growth ...

Research of zebrafish neurons may lead to understanding of birth defects like spina bifida

2014-02-18

COLUMBIA, Mo. – The zebrafish, a tropical freshwater fish similar to a minnow and native to the southeastern Himalayan region, is well established as a key tool for researchers studying human diseases, including brain disorders. Using zebrafish, scientists can determine how individual neurons develop, mature and support basic functions like breathing, swallowing and jaw movement. Researchers at the University of Missouri say that learning about neuronal development and maturation in zebrafish could lead to a better understanding of birth defects such as spina bifida in ...

Prison-based education declined during economic downturn, study finds

2014-02-18

State-level spending on prison education programs declined sharply during the economic downturn, with the sharpest drop occurring in states that incarcerate the most prisoners, according to a new RAND Corporation study.

Large states cut spending by an average of 10 percent between the 2009 and 2012 fiscal years, while medium-sized states cut spending by 20 percent, according to the study.

"There has been a dramatic contraction of the prison education system, particularly those programs focused on academic instruction versus vocational training," said Lois Davis, the ...

Miriam Hospital study shows social gaming site effective weight loss tool

2014-02-18

(PROVIDENCE, R.I.) -- Researchers from The Miriam Hospital have found that DietBet, a web-based commercial weight loss program that pairs financial incentives with social influence, delivers significant weight losses. The study and its findings have been published in the current issue of the open access publication JMIR Serious Games.

Tricia Leahey, Ph.D., lead researcher at The Miriam Hospital Weight Control and Diabetes Research Center, sought to examine weight losses associated with the social gaming website and contributing factors to gauge the success of such web-based ...

Rife with hype, exoplanet study needs patience and refinement

2014-02-18

Imagine someone spent months researching new cities to call home using low-resolution images of unidentified skylines. The pictures were taken from several miles away with a camera intended for portraits, and at sunset. From these fuzzy snapshots, that person claims to know the city's air quality, the appearance of its buildings, and how often it rains.

This technique is similar to how scientists often characterize the atmosphere — including the presence of water and oxygen — of planets outside of Earth's solar system, known as exoplanets, according to a review of exoplanet ...

Frequent flyers, bottle gourds crossed the ocean many times

2014-02-18

Bottle gourds traveled the Atlantic Ocean from Africa and were likely domesticated many times in various parts of the New World, according to a team of scientists who studied bottle gourd genetics to show they have an African, not Asian ancestry.

"Beginning in the 1950s we thought that bottle gourds floated across the ocean from Africa," said Logan Kistler, post-doctoral researcher in anthropology, Penn State. "However, a 2005 genetic study of gourds suggested an Asian origin."

Domesticated bottle gourds are ubiquitous around the world in tropical and temperate areas ...

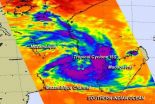

NASA sees Tropical Cyclone 15S form in the Mozambique Channel

2014-02-18

NASA's Aqua satellite passed over Tropical Cyclone 15S as it formed in the Mozambique Channel on Feb. 18 and the AIRS instrument aboard gathered infrared data on its cloud top temperatures and potential.

NASA's Aqua satellite passed over Tropical cyclone 15S on Feb. 18 at 10:53 a.m. EST. The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder or AIRS instrument captured infrared data on the tropical system that showed the highest cloud tops and strongest thunderstorms were in a band that stretched from the east to the south of the center. Cloud top temperatures were near -63F/-52C, indicating ...

Agricultural productivity loss as a result of soil and crop damage from flooding

2014-02-18

URBANA, Ill. – The Cache River Basin, which once drained more than 614,100 acres across six southern Illinois counties, has changed substantively since the ancient Ohio River receded. The basin contains a slow-moving, meandering river; fertile soils and productive farmlands; deep sand and gravel deposits; sloughs and uplands; and one of the most unique and diverse natural habitats in Illinois and the nation.

According to a recent University of Illinois study, the region's agricultural lands dodged a bullet due to the timing of the great flood of April 2011 when the Ohio ...

GW spirituality and health pioneer publishes paper on development of the field

2014-02-18

WASHINGTON (Feb. 18, 2014) — While spirituality played a significant role in health care for centuries, technological advances in the 20th century overshadowed this more human side of medicine. Christina Puchalski, M.D.'94, RESD'97, founder and director of the George Washington University (GW) Institute for Spirituality and Health and professor of medicine at the GW School of Medicine and Health Sciences (SMHS), and co-authors published a commentary in Academic Medicine on the history of spirituality and health, the movement to reclaim medicine's spiritual roots, and the ...