(Press-News.org) In the battle against infection, immune cells are the body's offense and defense—some cells go on the attack while others block invading pathogens. It has long been known that a population of blood stem cells that resides in the bone marrow generates all of these immune cells. But most scientists have believed that blood stem cells participate in battles against infection in a delayed way, replenishing immune cells on the front line only after they become depleted.

Now, using a novel microfluidic technique, researchers at Caltech have shown that these stem cells might be more actively involved, sensing danger signals directly and quickly producing new immune cells to join the fight.

"It has been most people's belief that the bone marrow has the function of making these cells but that the response to infection is something that happens locally, at the infection site," says David Baltimore, president emeritus and the Robert Andrews Millikan Professor of Biology at Caltech. "We've shown that these bone marrow cells themselves are sensitive to infection-related molecules and that they respond very rapidly. So the bone marrow is actually set up to respond to infection."

The study, led by Jimmy Zhao, a graduate student in the UCLA-Caltech Medical Scientist Training Program, will appear in the April 3 issue of the journal Cell Stem Cell.

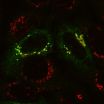

In the work, the researchers show that blood stem cells have all the components needed to detect an invasion and to mount an inflammatory response. They show, as others have previously, that these cells have on their surface a type of receptor called a toll-like receptor. The researchers then identify an entire internal response pathway that can translate activation of those receptors by infection-related molecules, or danger signals, into the production of cytokines, signaling molecules that can crank up immune-cell production. Interestingly, they show for the first time that the transcription factor NF-κB, known to be the central organizer of the immune response to infection, is part of that response pathway.

To examine what happens to a blood stem cell once it is activated by a danger signal, the Baltimore lab teamed up with chemists from the lab of James Heath, the Elizabeth W. Gilloon Professor and professor of chemistry at Caltech. They devised a microfluidic chip—printed in flexible silicon on a glass slide, complete with input and output ports, control valves, and thousands of tiny wells—that would enable single-cell analysis. At the bottom of each well, they attached DNA molecules in strips and introduced a flow of antibodies—pathogen-targeting proteins of the immune system—that had complementary DNA. They then added the stem cells along with infection-related molecules and incubated the whole sample. Since the antibodies were selected based on their ability to bind to certain cytokines, they specifically captured any of those cytokines released by the cells after activation. When the researchers added a secondary antibody and a dye, the cytokines lit up. "They all light up the same color, but you can tell which is which because you've attached the DNA in an orderly fashion," explains Baltimore. "So you've got both visualization and localization that tells you which molecule was secreted." In this way, they were able to measure, for example, that the cytokine IL-6 was secreted most frequently—by 21.9 percent of the cells tested.

"The experimental challenges here were significant—we needed to isolate what are actually quite rare cells, and then measure the levels of a dozen secreted proteins from each of those cells," says Heath. "The end result was sort of like putting on a new pair of glasses—we were able to observe functional properties of these stem cells that were totally unexpected."

The team found that blood stem cells produce a surprising number and variety of cytokines very rapidly. In fact, the stem cells are even more potent generators of cytokines than other previously known cytokine producers of the immune system. Once the cytokines are released, it appears that they are able to bind to their own cytokine receptors or those on other nearby blood stem cells. This stimulates the bound cells to differentiate into the immune cells needed at the site of infection.

"This does now change the view of the potential of bone marrow cells to be involved in inflammatory reactions," says Baltimore.

Heath notes that the collaboration benefited greatly from Caltech's support of interdisciplinary work. "It is a unique and fertile environment," he says, "one that encourages scientists from different disciplines to harness their disparate areas of expertise to solve tough problems like this one."

INFORMATION:

Additional coauthors on the paper, "Conversion of danger signals into cytokine signals by hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells for regulation of stress-induced hematopoiesis," are Chao Ma, Ryan O'Connell, Arnav Mehta, and Race DiLoreto. The work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institutes of Health, a National Research Service Award, the UCLA-Caltech Medical Scientist Training Program, a Rosen Fellowship, a Pathway to Independence Award, and an American Cancer Society Research Grant.

A changing view of bone marrow cells

Caltech researchers show that the cells are actively involved in sensing infection

2014-02-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Compound improves cardiac function in mice with genetic heart defect, MU study finds

2014-02-20

COLUMBIA, Mo. — Congenital heart disease is the most common form of birth defect, affecting one out of every 125 babies, according to the National Institutes of Health. Researchers from the University of Missouri recently found success using a drug to treat laboratory mice with one form of congenital heart disease, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy — a weakening of the heart caused by abnormally thick muscle. By suppressing a faulty protein, the researchers reduced the thickness of the mice's heart muscles and improved their cardiac functioning.

Maike Krenz, M.D., has been ...

Turning back the clock on aging muscles?

2014-02-20

A study co-published in Nature Medicine this week by University of Toronto researcher Penney Gilbert has determined a stem cell based method for restoring strength to damaged skeletal muscles of the elderly.

Skeletal muscles are some of the most important muscles in the body, supporting functions such as sitting, standing, blinking and swallowing. In aging individuals, the function of these muscles significantly decreases.

"You lose fifteen percent of muscle mass every single year after the age of 75, a trend that is irreversible," cites Gilbert, Assistant Professor ...

Researchers say distant quasars could close a loophole in quantum mechanics

2014-02-20

In a paper published this week in the journal Physical Review Letters, MIT researchers propose an experiment that may close the last major loophole of Bell's inequality — a 50-year-old theorem that, if violated by experiments, would mean that our universe is based not on the textbook laws of classical physics, but on the less-tangible probabilities of quantum mechanics.

Such a quantum view would allow for seemingly counterintuitive phenomena such as entanglement, in which the measurement of one particle instantly affects another, even if those entangled particles are ...

Crop species may be more vulnerable to climate change than we thought

2014-02-20

A new study by a Wits University scientist has overturned a long-standing hypothesis about plant speciation (the formation of new and distinct species in the course of evolution), suggesting that agricultural crops could be more vulnerable to climate change than was previously thought.

Unlike humans and most other animals, plants can tolerate multiple copies of their genes – in fact some plants, called polyploids, can have more than 50 duplicates of their genomes in every cell. Scientists used to think that these extra genomes helped polyploids survive in new and extreme ...

Surprising culprit found in cell recycling defect

2014-02-20

To remain healthy, the body's cells must properly manage their waste recycling centers. Problems with these compartments, known as lysosomes, lead to a number of debilitating and sometimes lethal conditions.

Reporting in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified an unusual cause of the lysosomal storage disorder called mucolipidosis III, at least in a subset of patients. This rare disorder causes skeletal and heart abnormalities and can result in a shortened lifespan. ...

MD Anderson researcher uncovers some of the ancient mysteries of leprosy

2014-02-20

Research at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center is finally unearthing some of the ancient mysteries behind leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease, which has plagued mankind throughout history. The new research findings appear in the current edition of journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. According to this new hypothesis, the disease might be the oldest human-specific infection, with roots that likely stem back millions of years.

There are hundreds of thousands of new cases of leprosy worldwide each year, but the disease is rare in the United States, ...

Sustainable manufacturing system to better consider the human component

2014-02-20

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Engineers at Oregon State University have developed a new approach toward "sustainable manufacturing" that begins on the factory floor and tries to encompass the totality of manufacturing issues – including economic, environmental, and social impacts.

This approach, they say, builds on previous approaches that considered various facets of sustainability in a more individual manner. Past methods often worked backward from a finished product and rarely incorporated the complexity of human social concerns.

The findings have been published in the Journal ...

New calibration confirms LUX dark matter results

2014-02-20

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — A new high-accuracy calibration of the LUX (Large Underground Xenon) dark matter detector demonstrates the experiment's sensitivity to ultra-low energy events. The new analysis strongly confirms the result that low-mass dark matter particles were a no-show during the detector's initial run, which concluded last summer.

The first dark matter search results from LUX detector were announced last October. The detector proved to be exquisitely sensitive, but found no evidence of the dark matter particles during its first 90-day run, ruling ...

Better broccoli, enhanced anti-cancer benefits with longer shelf life

2014-02-20

URBANA, Ill. – While researching methods to increase the already well-recognized anti-cancer properties of broccoli, researchers at the University of Illinois also found a way to prolong the vegetable's shelf life.

And, according to the recently published study, the method is a natural and inexpensive way to produce broccoli that has even more health benefits and won't spoil so quickly on your refrigerator shelf.

Jack Juvik, a U of I crop sciences researcher, explained that the combined application of two compounds, both are natural products extracted from plants, increased ...

Smaller meals more times per day may curb obesity in cats

2014-02-20

URBANA, Ill. – Just as with people, feline obesity is most often linked to excessive food intake or not enough physical activity. Attempts to cut back on calories alone often result in failed weight loss or weight regain in both people and their pets.

So how do you encourage your cat to get more exercise?

Researchers from the University of Illinois interested in finding a method to maintain healthy body weight in cats, looked at a previously suggested claim that increased meal frequency could help to increase overall physical activity.

The idea is to feed cats the ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Bacteria frozen in ancient underground ice cave found to be resistant against 10 modern antibiotics

Rhododendron-derived drugs now made by bacteria

Admissions for child maltreatment decreased during first phase of COVID-19 pandemic, but ICU admissions increased later

Power in motion: transforming energy harvesting with gyroscopes

Ketamine high NOT related to treatment success for people with alcohol problems, study finds

1 in 6 Medicare beneficiaries depend on telehealth for key medical care

Maps can encourage home radon testing in the right settings

Exploring the link between hearing loss and cognitive decline

Machine learning tool can predict serious transplant complications months earlier

Prevalence of over-the-counter and prescription medication use in the US

US child mental health care need, unmet needs, and difficulty accessing services

Incidental rotator cuff abnormalities on magnetic resonance imaging

Sensing local fibers in pancreatic tumors, cancer cells ‘choose’ to either grow or tolerate treatment

Barriers to mental health care leave many children behind, new data cautions

Cancer and inflammation: immunologic interplay, translational advances, and clinical strategies

Bioactive polyphenolic compounds and in vitro anti-degenerative property-based pharmacological propensities of some promising germplasms of Amaranthus hypochondriacus L.

AI-powered companionship: PolyU interfaculty scholar harnesses music and empathetic speech in robots to combat loneliness

Antarctica sits above Earth’s strongest “gravity hole.” Now we know how it got that way

Haircare products made with botanicals protects strands, adds shine

Enhanced pulmonary nodule detection and classification using artificial intelligence on LIDC-IDRI data

Using NBA, study finds that pay differences among top performers can erode cooperation

Korea University, Stanford University, and IESGA launch Water Sustainability Index to combat ESG greenwashing

Molecular glue discovery: large scale instead of lucky strike

Insulin resistance predictor highlights cancer connection

Explaining next-generation solar cells

Slippery ions create a smoother path to blue energy

Magnetic resonance imaging opens the door to better treatments for underdiagnosed atypical Parkinsonisms

National poll finds gaps in community preparedness for teen cardiac emergencies

One strategy to block both drug-resistant bacteria and influenza: new broad-spectrum infection prevention approach validated

Survey: 3 in 4 skip physical therapy homework, stunting progress

[Press-News.org] A changing view of bone marrow cellsCaltech researchers show that the cells are actively involved in sensing infection