(Press-News.org) ANN ARBOR—An ancient chemical, present for billions of years, appears to have helped proteins function properly since time immemorial.

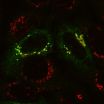

Proteins are the body's workhorses, and like horses they often work in teams. There exists a modern day team of multiple chaperone proteins that help other proteins fold into the complex 3D shapes they must achieve to function. This is necessary to avert many serious diseases caused when proteins misbehave.

But what happened before this team of chaperones was formed? How did the primordial cells that were the ancestors of modern life keep their proteins folded and functional?

Scientists from the University of Michigan discovered that an extremely simple, ancient chemical called polyphosphate can perform the role of a chaperone. It likely played that role billions of years ago, and still keeps its old job today.

"Polyphosphate has likely been present since life began on Earth, and is thought to exist in all living creatures," said postdoctoral researcher Michael Gray. "This means it's extremely important, but no one really knew what it was for.

"We found that bacteria accumulate polyphosphate to defend against disease-causing, protein unfolding conditions. Purified polyphosphate works well to protect proteins in the test tube, showing that this simple chemical can substitute for the complex team of protein chaperones."

The discovery unravels a longstanding evolutionary mystery that could lead to new strategies for treating protein folding diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, which occur when proteins misfold or pile up.

"Once we know how to manipulate the levels of polyphosphate in cells and organisms, we should be able to improve protein folding and develop countermeasures against protein folding diseases," said Ursula Jakob, the U-M professor in charge of the research.

INFORMATION:

Their work appears in the journal Molecular Cell. It was funded by the National Institutes of Health and Howard Hughes Medical Institute. U-M co-authors include Wei-Yun Wholey, Claudia Cremers, Robert Bender, Antje Mueller-Schickert, Nico Wagner, Nathaniel Hock, Adam Krieger, Erica Smith and James Bardwell.

Chemical chaperones have helped proteins do their jobs for billions of years

2014-02-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists discover 11 new genes affecting blood pressure

2014-02-20

New research from Queen Mary University of London has discovered 11 new DNA sequence variants in genes influencing high blood pressure and heart disease.

Identifying the new genes contributes to our growing understanding of the biology of blood pressure and, researchers believe, will eventually influence the development of new treatments. More immediately the study highlights opportunities to investigate the use of existing drugs for cardiovascular diseases.

The large international study, published today in the American Journal of Human Genetics, examined the DNA ...

A changing view of bone marrow cells

2014-02-20

In the battle against infection, immune cells are the body's offense and defense—some cells go on the attack while others block invading pathogens. It has long been known that a population of blood stem cells that resides in the bone marrow generates all of these immune cells. But most scientists have believed that blood stem cells participate in battles against infection in a delayed way, replenishing immune cells on the front line only after they become depleted.

Now, using a novel microfluidic technique, researchers at Caltech have shown that these stem cells might ...

Compound improves cardiac function in mice with genetic heart defect, MU study finds

2014-02-20

COLUMBIA, Mo. — Congenital heart disease is the most common form of birth defect, affecting one out of every 125 babies, according to the National Institutes of Health. Researchers from the University of Missouri recently found success using a drug to treat laboratory mice with one form of congenital heart disease, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy — a weakening of the heart caused by abnormally thick muscle. By suppressing a faulty protein, the researchers reduced the thickness of the mice's heart muscles and improved their cardiac functioning.

Maike Krenz, M.D., has been ...

Turning back the clock on aging muscles?

2014-02-20

A study co-published in Nature Medicine this week by University of Toronto researcher Penney Gilbert has determined a stem cell based method for restoring strength to damaged skeletal muscles of the elderly.

Skeletal muscles are some of the most important muscles in the body, supporting functions such as sitting, standing, blinking and swallowing. In aging individuals, the function of these muscles significantly decreases.

"You lose fifteen percent of muscle mass every single year after the age of 75, a trend that is irreversible," cites Gilbert, Assistant Professor ...

Researchers say distant quasars could close a loophole in quantum mechanics

2014-02-20

In a paper published this week in the journal Physical Review Letters, MIT researchers propose an experiment that may close the last major loophole of Bell's inequality — a 50-year-old theorem that, if violated by experiments, would mean that our universe is based not on the textbook laws of classical physics, but on the less-tangible probabilities of quantum mechanics.

Such a quantum view would allow for seemingly counterintuitive phenomena such as entanglement, in which the measurement of one particle instantly affects another, even if those entangled particles are ...

Crop species may be more vulnerable to climate change than we thought

2014-02-20

A new study by a Wits University scientist has overturned a long-standing hypothesis about plant speciation (the formation of new and distinct species in the course of evolution), suggesting that agricultural crops could be more vulnerable to climate change than was previously thought.

Unlike humans and most other animals, plants can tolerate multiple copies of their genes – in fact some plants, called polyploids, can have more than 50 duplicates of their genomes in every cell. Scientists used to think that these extra genomes helped polyploids survive in new and extreme ...

Surprising culprit found in cell recycling defect

2014-02-20

To remain healthy, the body's cells must properly manage their waste recycling centers. Problems with these compartments, known as lysosomes, lead to a number of debilitating and sometimes lethal conditions.

Reporting in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified an unusual cause of the lysosomal storage disorder called mucolipidosis III, at least in a subset of patients. This rare disorder causes skeletal and heart abnormalities and can result in a shortened lifespan. ...

MD Anderson researcher uncovers some of the ancient mysteries of leprosy

2014-02-20

Research at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center is finally unearthing some of the ancient mysteries behind leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease, which has plagued mankind throughout history. The new research findings appear in the current edition of journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. According to this new hypothesis, the disease might be the oldest human-specific infection, with roots that likely stem back millions of years.

There are hundreds of thousands of new cases of leprosy worldwide each year, but the disease is rare in the United States, ...

Sustainable manufacturing system to better consider the human component

2014-02-20

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Engineers at Oregon State University have developed a new approach toward "sustainable manufacturing" that begins on the factory floor and tries to encompass the totality of manufacturing issues – including economic, environmental, and social impacts.

This approach, they say, builds on previous approaches that considered various facets of sustainability in a more individual manner. Past methods often worked backward from a finished product and rarely incorporated the complexity of human social concerns.

The findings have been published in the Journal ...

New calibration confirms LUX dark matter results

2014-02-20

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — A new high-accuracy calibration of the LUX (Large Underground Xenon) dark matter detector demonstrates the experiment's sensitivity to ultra-low energy events. The new analysis strongly confirms the result that low-mass dark matter particles were a no-show during the detector's initial run, which concluded last summer.

The first dark matter search results from LUX detector were announced last October. The detector proved to be exquisitely sensitive, but found no evidence of the dark matter particles during its first 90-day run, ruling ...