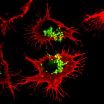

(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA, CA—A collaborative effort between researchers at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies and the University of California, San Diego, successfully used human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells derived from patients with Rett syndrome to replicate autism in the lab and study the molecular pathogenesis of the disease.

Their findings, published in the Nov. 12, 2010, issue of Cell, revealed disease-specific cellular defects, such as fewer functional connections between Rett neurons, and demonstrated that these symptoms are reversible, raising the hope that, one day, autism maybe turn into a treatable condition.

"Mental disease and particularly autism still carry the stigma of bad parenting," says lead author Alysson Muotri, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Medicine at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine. "We show very clearly that autism is a biological disease that is caused by a developmental defect directly affecting brain cells."

Rett syndrome is the most physically disabling of the autism spectrum disorders. Primarily affecting girls, the symptoms of Rett syndrome often become apparent just after they have learned to walk and say a few words. Then, the seemingly normal development slows down and eventually the infants regress, loosing speech and motor skills, developing stereotypical movements and autistic characteristics.

Almost all cases of the disease are caused by a single mutation in the MeCP2 gene, which is involved in the regulation of global gene expression, leading to a host of symptoms that can vary widely in their severity.

"Rett syndrome is sometimes considered a 'Rosetta Stone' that can help us to understand other developmental neurological disorders since it shares genetic links with other conditions such as autism and schizophrenia," says first author Carol Marchetto, Ph.D., a postdoctoral researcher in the Laboratory of Genetics at the Salk Institute.

In the past, scientists had been limited to study the brains of people with autistic spectrum disorders via imaging technologies or postmortem brain tissues. Now, the ability to obtain iPS cells from patients' skin cells, which can be encouraged to develop into the cell type damaged by the disease gives scientists an unprecedented view of autism.

"It is quite amazing that we can recapitulate a psychiatric disease in a Petri Dish," says lead author Fred Gage, Ph.D., a professor in the Salk's Laboratory of Genetics and holder of the Vi and John Adler Chair for Research on Age-Related Neurodegenerative Diseases. "Being able to study Rett neurons in a dish allows us to identify subtle alterations in the functionality of the neuronal circuitry that we never had access to before."

Marchetto started with skin biopsies taken from four patients carrying four different mutations in the MeCP2 gene and a healthy control. By exposing the skin cells to four reprogramming factors, she turned back the clock, triggering the cells to look and act like embryonic stem cells. Known at this point as induced pluripotent stem cells, the Rett-derived cells were indistinguishable from their normal counterparts.

It was only after she had patiently coaxed the iPS cells to develop into fully functioning neurons—a process that can take up to several months—that she was able to discern differences between the two. Neurons carrying the MeCP2 mutations had smaller cell bodies, a reduced number of synapses and dendritic spines, specialized structures that enable cell-cell communication, as well as electrophysical defects, indicating that things start to go wrong early in development.

Since insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1)—a hormone which, among other things, has a role in regulating cell growth and neuronal development—was able to reverse some of the symptoms of Rett syndrome in a mouse model of disease, the Salk researchers tested whether IGF-1 could restore proper function to human Rett neurons grown in culture.

"IGF-1 treatment increased the number of synapses and spines reverting the neuronal phenotype closer to normal," says Gage. "This suggests that the autistic phenotype is not permanent and could be, at least partially, reversible."

Muotri is particularly excited about the prospect of finding a drug treatment for Rett syndrome and other forms of autism: "We now know that we can use disease-specific iPS cells to recreate mental disorders and start looking for new drugs based on measurable molecular defects."

INFORMATION:

Researchers who also contributed to the work include Cassiano Carromeu and Allan Acab in the Department of Pediatrics/Cellular & Molecular Medicine at the University of California, San Diego, Diana Yu and Yangling Mu in the Laboratory of Genetics at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, Gene Yeo in the School of Medicine at the University of California, San Diego, as well as Gong Chen in the Department of Biology at the Pennsylvania State University.

This work was supported by the Emerald Foundation Young Investigator Award, the National Institutes of Health through the NIH Director's New Innovator Award Program, the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, The Lookout Fund and the Picower Foundation.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world's preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probe fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative, and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer's, diabetes, and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines.

Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, M.D., the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

The Salk Institute proudly celebrates five decades of scientific excellence in basic research.

Modeling autism in a dish

2010-11-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NIAID media tipsheet: Annual Meeting of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology

2010-11-12

WHAT:

The 2010 Annual Meeting of the American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (ACAAI) brings together leading allergists and immunologists from around the world.

WHO:

Scientists supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health, will present their latest research findings at the ACAAI Annual Meeting. For more than 60 years, NIAID has supported allergy and immunology research at U.S. and international institutions and conducted studies within its own laboratories to improve the health ...

UCSD researchers create autistic neuron model

2010-11-12

Using induced pluripotent stem cells from patients with Rett syndrome, scientists at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have created functional neurons that provide the first human cellular model for studying the development of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and could be used as a tool for drug screening, diagnosis and personalized treatment.

The research, led by Alysson R. Muotri, PhD, assistant professor of pediatrics, will be published in the November 12 issue of the journal Cell.

"This work is important because it puts us in a translational ...

New urine test could diagnose acute kidney injury

2010-11-12

The presence of certain markers in the urine might be a red flag for acute kidney injury (AKI), according to a study appearing in an upcoming issue of the Journal of the American Society Nephrology (JASN). The results suggest that a simple urine test could help prevent cases of kidney failure.

Unlike heart or brain injuries, which show obvious outward signs, physical symptoms are not typically present with AKI. Researchers have been looking for markers of AKI, with the hope that early detection will lead to early therapy to prevent kidney failure. Richard Zager, MD (Clinical ...

Keeping the daily clock ticking in a fluctuating environment: Hints from a green alga

2010-11-12

Researchers in France have uncovered a mechanism which explains how biological clocks accurately synchronize to the day/night cycle despite large fluctuations in light intensity during the day and from day to day. Following the identification of two central "clock genes" of a green alga, Ostreococcus tauri, a mathematical model reproducing their daily activity profiles has revealed that their internal clock is influenced by the naturally varying light levels throughout the day only at periods when it needs resetting. The results found by the biologists at Oceanologic Observatory ...

Cats show perfect balance even in their lapping

2010-11-12

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — Cat fanciers everywhere appreciate the gravity-defying grace and exquisite balance of their feline friends. But do they know those traits extend even to the way cats lap milk?

Researchers at MIT, Virginia Tech and Princeton University analyzed the way domestic and big cats lap and found that felines of all sizes take advantage of a perfect balance between two physical forces. The results will be published in the November 11 online issue of the journal Science.

It was known that when they lap, cats extend their tongues straight down toward the bowl ...

New explanation for the origin of high species diversity

2010-11-12

PHILADELPHIA—An international team of scientists, including a leading evolutionary biologist from the Academy of Natural Sciences, have reset the agenda for future research in the highly diverse Amazon region by showing that the extraordinary diversity found there is much older than generally thought.

The findings from this study, which draws on research by the Academy's Dr. John Lundberg and other scientists, were published as a review article in this week's edition of Science. The study shows that Amazonian diversity has evolved as by-product of the Andean mountain ...

Tropical forest diversity increased during ancient global warming event

2010-11-12

The steamiest places on the planet are getting warmer. Conservative estimates suggest that tropical areas can expect temperature increases of 3 degrees Celsius by the end of this century. Does global warming spell doom for rainforests? Maybe not. Carlos Jaramillo, staff scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, and colleagues report in the journal Science that nearly 60 million years ago rainforests prospered at temperatures that were 3-5 degrees higher and at atmospheric carbon dioxide levels 2.5 times today's levels.

"We're going to have a novel climate ...

Study finds the mind is a frequent, but not happy, wanderer

2010-11-12

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. -- People spend 46.9 percent of their waking hours thinking about something other than what they're doing, and this mind-wandering typically makes them unhappy. So says a study that used an iPhone web app to gather 250,000 data points on subjects' thoughts, feelings, and actions as they went about their lives.

The research, by psychologists Matthew A. Killingsworth and Daniel T. Gilbert of Harvard University, is described this week in the journal Science.

"A human mind is a wandering mind, and a wandering mind is an unhappy mind," Killingsworth and ...

Voluntary cooperation and monitoring lead to success

2010-11-12

FRANKFURT. Many imminent problems facing the world today, such as deforestation, overfishing, or climate change, can be described as commons problems. The solution to these problems requires cooperation from hundreds and thousands of people. Such large scale cooperation, however, is plagued by the infamous cooperation dilemma. According to the standard prediction, in which each individual follows only his own interests, large-scale cooperation is impossible because free riders enjoy common benefits without bearing the cost of their provision. Yet, extensive field evidence ...

New vaccine hope in fight against pneumonia and meningitis

2010-11-12

A new breakthrough in the fight against pneumonia, meningitis and septicaemia has been announced today by scientists in Dublin and Leicester.

The discovery will lead to a dramatic shift in our understanding of how the body's immune system responds to infection caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae and pave the way for more effective vaccines.

The collaborative research, jointly led by Dr Ed Lavelle from Trinity College Dublin and Dr Aras Kadioglu from the University of Leicester, with Dr Edel McNeela of TCD as its lead author, has been published in the international peer-reviewed ...