Watching how the brain works

University of Miami researchers develop a method to visualize protein interactions in a living organism's brain

2014-02-24

(Press-News.org) Coral Gables, Fla (Feb. 19, 2014) -- There are more than a trillion cells called neurons that form a labyrinth of connections in our brains. Each of these neurons contains millions of proteins that perform different functions. Exactly how individual proteins interact to form the complex networks of the brain still remains as a mystery that is just beginning to unravel.

For the first time, a group of scientists has been able to observe intact interactions between proteins, directly in the brain of a live animal. The new live imaging approach was developed by a team of researchers at the University of Miami (UM).

"Our ultimate goal is to create the systematic survey of protein interactions in the brain," says Akira Chiba, professor of Biology in the College of Arts and Sciences at UM and lead investigator of the project. "Now that the genome project is complete, the next step is to understand what the proteins coded by our genes do in our body."

The new technique will allow scientists to visualize the interactions of proteins in the brain of an animal, along different points throughout its development, explains Chiba, who likens protein interactions to the way organisms associate with each other.

"We know that proteins are one billionth of a human in size. Nevertheless, proteins make networks and interact with each other, like social networking humans do," Chiba says. "The scale is very different, but it's the same behavior happening among the basic units of a given network."

The researchers chose embryos of the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) as an ideal model for the study. Because of its compact and transparent body, it is possible to visualize processes inside the Drosophila cells using a fluorescence lifetime imaging microscope (FLIM). The results of the observations are applicable to other animal brains, including the human brain.

The Drosophila embryos in the study contained a pair of fluorescent labeled proteins: a developmentally essential and ubiquitously present protein called Rho GTPase Cdc42 (cell division control protein 42), labeled with green fluorescent tag and its alleged signaling partner, the regulatory protein WASp (Wiskot-Aldrich Syndrome protein), labeled with red fluorescent tag. Together, these specialized proteins are believed to help neurons grow during brain development. The proteins were selected because the same (homolog) proteins exist in the human brain as well.

Previous methods required chemical or physical treatments that most likely disturb or even kill the cells. That made it impossible to study the protein interactions in their natural environment.

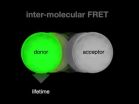

The current study addresses these challenges by using the occurrence of a phenomenon called Förster resonance energy transfer, or FRET. It occurs when two small proteins come within a very small distance of each other, (eight nanometers). The event is interpreted as the time and place where the particular protein interaction occurs within the living animal.

The findings show that FRET between the two interacting protein partners occurs within neurons, during the time and space that coincides with the formation of new synapses in the brain of the baby insect. Synapses connect individual neurons in the brain.

"Previous studies have demonstrated that Cdc42 and WASp can directly bind to each other in a test-tube, but this is the first direct demonstration that these two proteins are interacting within the brain," Chiba says.

INFORMATION:

The study is part of a larger project called in situ Protein-Protein Interaction Networks or isPIN. The findings are published by the journal PLoS ONE, in a paper titled "Imaging dynamic molecular signaling by the Cdc42 GTPase within the developing CNS"

Co-authors are Nima Sharifai, Hasitha Samarajeewa, Daichi Kamiyama Tzyy-Chyn Deng, and Maria Boulina, from the Department of Biology, College of Arts and Sciences, at UM. Kamiyama now works in the Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, at the University of California in San Francisco.

While the current project focuses on the neurons under the normal condition, future studies could include disease conditions, as well as specific classes of neurons, or even non-neuronal cells, bridging basic biology to advanced medicine.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Costs vary widely for care of children with congenital heart defects across US hospitals

2014-02-24

Ann Arbor, Mich. – Costs of care differ significantly across hospitals for children born with heart defects, according to new research led by a University of Michigan researcher. Congenital heart defects are known to be the most common birth defects, impacting nearly 1 in every 100 births.

The cost of care for children with congenital heart disease undergoing surgical repair varied as much as nine times across a large group of U.S. children's hospitals, says lead author Sara K. Pasquali, M.D., M.H.S., associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Michigan Medical ...

Opioid abuse initiates specific protein interactions in neurons in brain's reward system

2014-02-24

(New York) – Identifying the specific pathways that promote opioid addiction, pain relief, and tolerance are crucial for developing more effective and less dangerous analgesics, as well as developing new treatments for addiction. Now, new research from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai reveals that opiate use alters the activity of a specific protein needed for the normal functioning of the brain's reward center. Investigators were able to block the protein, as well as increase its expression in the mouse nucleus accumbens, a key component of the brain's reward ...

Abdominal fat accumulation prevented by unsaturated fat

2014-02-24

New research from Uppsala University shows that saturated fat builds more fat and less muscle than polyunsaturated fat. This is the first study on humans to show that the fat composition of food not only influences cholesterol levels in the blood and the risk of cardiovascular disease but also determines where the fat will be stored in the body. The findings have recently been published in the American journal Diabetes.

The study involved 39 young adult men and women of normal weight, who ate 750 extra calories per day for seven weeks. The goal was for them to gain three ...

Medical researchers use light to quickly and easily measure blood's clotting properties

2014-02-24

VIDEO:

This video shows the rapid "twinkling " or intensity fluctuations of the speckle pattern in a drop of unclotted whole blood. The rapid "twinkling " is due to the fast thermally-driven motion...

Click here for more information.

WASHINGTON, Feb. 24—Defective blood coagulation is one of the leading causes of preventable death in patients who have suffered trauma or undergone surgery. The body's natural defense against severe blood loss is the clotting ...

NIST microanalysis technique makes the most of small nanoparticle samples

2014-02-24

Researchers from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have demonstrated that they can make sensitive chemical analyses of minute samples of nanoparticles by, essentially, roasting them on top of a quartz crystal. The NIST-developed technique, "microscale thermogravimetric analysis," holds promise for studying nanomaterials in biology and the environment, where sample sizes often are quite small and larger-scale analysis won't work.*

Chemical analysis of nanoparticles is a challenging task, and not just because ...

New biological scaffold offers promising foundation for engineered tissues

2014-02-24

Our cells don't live in a vacuum. They are surrounded by a complex, nurturing matrix that is essential for many biological functions, including growth and healing.

In all multicellular organisms, including people, cells make their own extracellular matrix. But in the lab, scientists attempting to grow tissue must provide a scaffold for cells to latch onto as they grow and proliferate. This engineered tissue has potential to repair or replace virtually any part of our bodies.

Typically, researchers construct scaffolds from synthetic materials or natural animal or human ...

Is previous hypoglycemia a risk factor for future hypoglycemic episodes?

2014-02-24

New Rochelle, NY, February 24, 2014—The automatic "threshold suspend" (TS) feature of an insulin pump helps prevent life-threatening hypoglycemic events when the device's sensor detects blood glucose concentrations below the preset threshold. However, in individuals with type 1 diabetes who have had previous episodes of hypoglycemia the TS feature may be less effective at preventing subsequent events, according to important new results from the ASPIRE study published in Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics (DTT), a peer-reviewed journal from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers. ...

Vitamin water: Measuring essential nutrients in the ocean

2014-02-24

The phrase, 'Eat your vitamins,' applies to marine animals just like humans. Many vitamins, including B-12, are elusive in the ocean environment.

University of Washington researchers used new tools to measure and track B-12 vitamins in the ocean. Once believed to be manufactured only by marine bacteria, the new results show that a whole different class of organism, archaea, can supply this essential vitamin. The results were presented Feb. 24 at the Ocean Sciences meeting in Honolulu.

"The dominant paradigm has been bacteria are out there, making B-12, but it turns ...

OU researcher and team discover disease-causing bacteria in dental plaque preserved for 1,000 years

2014-02-24

When a University of Oklahoma researcher and an international team of experts analyzed the dental calculus or plaque from teeth preserved for 1,000 years, the results revealed human health and dietary information never seen before. The team discovered disease-causing bacteria in a German Medieval population, which is the same or very similar to inflammatory disease-causing bacteria in humans today—unlikely scientific results given modern hygiene and dental health practices.

Christina Warinner, research associate in the Molecular Anthropologies Laboratories, OU College ...

Gauging what it takes to heal a disaster-ravaged forest

2014-02-24

Recovering from natural disasters usually means rebuilding infrastructure and reassembling human lives. Yet ecologically sensitive areas need to heal, too, and scientists are pioneering new methods to assess nature's recovery and guide human intervention.

The epicenter of China's devastating Wenchuan earthquake in 2008 was in the Wolong Nature Reserve, a globally important valuable biodiversity hotspot and home to the beloved and endangered giant pandas. Not only did the quake devastate villages and roads, but the earth split open and swallowed sections of the forests ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Ten-point plan to deliver climate education unveiled by experts

Team led by UC San Diego researchers selected for prestigious global cancer prize

Study: Reported crop yield gains from breeding may be overstated

Stem cells from human baby teeth show promise for treating cerebral palsy

Chimps’ love for crystals could help us understand our own ancestors’ fascination with these stones

Vaginal estrogen therapy not linked to cancer recurrence in survivors of endometrial cancer

How estrogen helps protect women from high blood pressure

Breaking the efficiency barrier: Researchers propose multi-stage solar system to harness the full spectrum

A new name, a new beginning: Building a green energy future together

From algorithms to atoms: How artificial intelligence is accelerating the discovery of next-generation energy materials

Loneliness linked to fear of embarrassment: teen research

New MOH–NUS Fellowship launched to strengthen everyday ethics in Singapore’s healthcare sector

Sungkyunkwan University researchers develop next-generation transparent electrode without rare metal indium

What's going on inside quantum computers?: New method simplifies process tomography

This ancient plant-eater had a twisted jaw and sideways-facing teeth

Jackdaw chicks listen to adults to learn about predators

Toxic algal bloom has taken a heavy toll on mental health

Beyond silicon: SKKU team presents Indium Selenide roadmap for ultra-low-power AI and quantum computing

Sugar comforts newborn babies during painful procedures

Pollen exposure linked to poorer exam results taken at the end of secondary school

7 hours 18 mins may be optimal sleep length for avoiding type 2 diabetes precursor

Around 6 deaths a year linked to clubbing in the UK

Children’s development set back years by Covid lockdowns, study reveals

Four decades of data give unique insight into the Sun’s inner life

Urban trees can absorb more CO₂ than cars emit during summer

Fund for Science and Technology awards $15 million to Scripps Oceanography

New NIH grant advances Lupus protein research

New farm-scale biochar system could cut agricultural emissions by 75 percent while removing carbon from the atmosphere

From herbal waste to high performance clean water material: Turning traditional medicine residues into powerful biochar

New sulfur-iron biochar shows powerful ability to lock up arsenic and cadmium in contaminated soils

[Press-News.org] Watching how the brain worksUniversity of Miami researchers develop a method to visualize protein interactions in a living organism's brain