(Press-News.org) NEW YORK (February 27, 2014) -- A new study led by Weill Cornell Medical College scientists shows that the most common genetic form of mental retardation and autism occurs because of a mechanism that shuts off the gene associated with the disease. The findings, published today in Science, also show that a drug that blocks this silencing mechanism can prevent fragile X syndrome – suggesting similar therapy is possible for 20 other diseases that range from mental retardation to multisystem failure.

Fragile X syndrome occurs mostly in boys, causing intellectual disability as well as telltale physical, behavioral and emotional traits. While researchers have known for more than two decades that the culprit behind the disease is an unusual mutation characterized by the excess repetition of a particular segment of the genetic code, they weren't sure why the presence of a large number of these repetitions – 200 or more – sets the disease process in motion.

Using stem cells from donated human embryos that tested positive for fragile X syndrome, the scientists discovered that early on in fetal development, messenger RNA -- a template for protein production -- begins sticking itself onto the fragile X syndrome gene's DNA. This binding appears to gum up the gene, making it inactive and unable to produce a protein crucial to the transmission of signals between brain cells.

"Until 11 weeks of gestation, the fragile X syndrome gene is active – it produces its messenger RNA and protein normally. Then, all of a sudden it turns off, and stays off for the rest of the patient's lifetime, causing fragile X syndrome. But scientists have not understood why this gene gets shut off," says senior author Dr. Samie Jaffrey, a professor of pharmacology at Weill Cornell Medical College. "We discovered that the messenger RNA can jam up one strand of the gene's DNA, shutting down the gene -- which was not known before.

"This is new biology -- an interaction between the RNA and the DNA of the fragile X syndrome gene causes disease," Dr. Jaffrey says. "We are coming to understand that RNAs are powerful molecules that can regulate gene expression, but this mechanism is completely novel -- and very exciting."

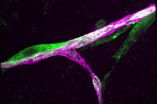

The malfunction occurs suddenly -- before the end of the first trimester in humans and after 50 days in laboratory embryonic stem cells. At that point, the messenger RNA produced by the fragile X syndrome gene makes what the researchers call an RNA-DNA duplex -- a particular arrangement of molecules in which the messenger RNA is stuck onto its DNA complement. (DNA produces two complementary strands of the genetic code responsible for human development and function. The four nucleic acids in the genomic code -- A, C, G, T -- have specific complements. In the case of fragile X syndrome, the repeat sequence in question is CGG. Therefore, RNA binds to its GCC complement on one strand of DNA.)

The RNA-DNA duplex then shuts down production of the fragile X syndrome gene, causing the loss of a protein needed for communication between brain cells. The gene then remains inactive for life. A normal fragile X gene -- one with fewer than 200 CGG repeats -- stays active in a person without the disorder, and produces the necessary protein. However, the mutant fragile X gene contains more than 200 CGG repeats, resulting in fragile X syndrome. Fragile X occurs in about 1 in 4,000 males and 1 in 8,000 females.

"Because the fragile X syndrome mutation is a repeat sequence, it is very easy for just a small portion of this sequence in the messenger RNA to find a matching repeat sequence on the DNA," Dr. Jaffrey says. "This is a unique feature of repeat sequences. When there are 200 or more repeats, the RNA-DNA interaction locks into place."

Hope for treatment – and other disorders

Dr. Jaffrey and his team, which includes researchers from The Scripps Research Institute in Florida and Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, sought to find out why the disease is switched on when the CGG repeat is present in 200 to as many as 1,000 copies.

"Utilizing traditional ways to solve this puzzle has been impossible," he says. "Human fragile X syndrome genes introduced into mice and cells in the laboratory never turn off, no matter how many CGG repeats the genes have."

So the scientists turned to human embryonic stem cells. Co-authors Dr. Zev Rosenwaks, director and physician-in-chief of the Ronald O. Perelman and Claudia Cohen Center for Reproductive Medicine and director of the Stem Cell Derivation Laboratory of Weill Cornell Medical College, and Dr. Nikica Zaninovic, assistant professor of reproductive medicine, generated stem cell lines from donated embryos that tested positive for fragile X syndrome.

"These stem cells were critical to the success of this research, because they alone allowed us to mimic what happens to the fragile X gene during embryonic development," says Dr. Dilek Colak, a postdoctoral scientist in Dr. Jaffrey's laboratory and the first author of the study.

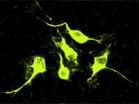

The stem cells were coaxed to become brain neurons, and at about 50 days, they differentiated in the same way that an embryo's brain is developing at 11-plus weeks when the fragile X syndrome gene is switched off.

The researchers then used a drug developed by co-author Dr. Matthew Disney of the Scripps Research Institute that binds to CGG in the fragile X gene's RNA before and after the 50-day switch. Strikingly, the gene never stopped producing its beneficial protein.

That suggests a potential prevention or treatment strategy for fragile X syndrome, Dr. Jaffrey says. "If a pregnant woman is told that her fetus carries the genetic mutation causing fragile X syndrome, we could potentially intervene and give the drug during gestation. This may delay or prevent the silencing of the fragile X gene, which could potentially significantly improve the outcome of these patients," he says.

The researchers are now looking for similar RNA-DNA duplexes in other trinucleotide repeat diseases, including Huntington's disease (a degenerative brain disease), myotonic dystrophy 1 and 2 (a multisystem progressive disease), Friedrich's ataxia (a progressive nervous system disorder), Jacobsen syndrome (an intellectual disorder), and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (a motor neuron disease), among others.

"This completely new mechanism by which RNAs can direct gene silencing may be involved in a lot of other diseases," Dr. Jaffrey says. "Our hope is that we can find drugs that interfere with this new type of disease process."

INFORMATION:

Co-authors include Michael S. Cohen from Weill Cornell Medical College; Dr. Wang-Yong Yang from The Scripps Research Institute; and Dr. Jeannine Gerhardt from Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

This work was supported by the Tri-Institutional Stem Cell Initiative (Tri-I SCI) Grant 2008-019, New York Stem Cell Foundation-Druckenmiller Fellowship, Life Sciences Research Foundation Fellowship and Tri-I SCI postdoctoral fellowship, and a FRAXA postdoctoral fellowship. Portions of this project not involving non-NIH registry stem cells were supported by NIH R01 MH80420 and NIH R01 GM079235.

Weill Cornell Medical College

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University's medical school located in New York City, is committed to excellence in research, teaching, patient care and the advancement of the art and science of medicine, locally, nationally and globally. Physicians and scientists of Weill Cornell Medical College are engaged in cutting-edge research from bench to bedside, aimed at unlocking mysteries of the human body in health and sickness and toward developing new treatments and prevention strategies. In its commitment to global health and education, Weill Cornell has a strong presence in places such as Qatar, Tanzania, Haiti, Brazil, Austria and Turkey. Through the historic Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar, the Medical College is the first in the U.S. to offer its M.D. degree overseas. Weill Cornell is the birthplace of many medical advances -- including the development of the Pap test for cervical cancer, the synthesis of penicillin, the first successful embryo-biopsy pregnancy and birth in the U.S., the first clinical trial of gene therapy for Parkinson's disease, and most recently, the world's first successful use of deep brain stimulation to treat a minimally conscious brain-injured patient. Weill Cornell Medical College is affiliated with NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, where its faculty provides comprehensive patient care at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. The Medical College is also affiliated with Houston Methodist. For more information, visit weill.cornell.edu.

Scientists uncover trigger for most common form of intellectual disability and autism

Finding may explain many brain disorders, lead to prevention and treatment

2014-02-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

CU-led study says Bering Land Bridge a long-term refuge for early Americans

2014-02-27

A new study led by the University of Colorado Boulder bolsters the theory that the first Americans, who are believed to have come over from northeast Asia during the last ice age, may have been isolated on the Bering Land Bridge for thousands of years before spreading throughout the Americas.

The theory, now known as the "Beringia Standstill," was first proposed in 1997 by two Latin American geneticists and refined in 2007 by a team led by the University of Tartu in Estonia that sampled mitrochondrial DNA from more than 600 Native Americans. The researchers found that ...

Fossils offer new clues into Native American's 'journey' and how they survived the last Ice Age

2014-02-27

Researchers have discovered how Native Americans may have survived the last Ice Age after splitting from their Asian relatives 25,000 years ago.

Academics at Royal Holloway, University of London, and the Universities of Colorado and Utah have analysed fossils which revealed that the ancestors of Native Americans may have set up home in a region between Siberia and Alaska which contained woody plants that they could use to make fires. The discovery breaks new ground as until now no-one had any idea of where the native Americans spent the next 10,000 years before they appeared ...

Researchers reveal the dual role of brain glycogen

2014-02-27

In 2007, in an article published in Nature Neuroscience, scientists at the Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB Barcelona) headed by Joan Guinovart, an authority on glycogen metabolism, reported that in Lafora Disease (LD), a rare and fatal neurodegenerative condition that affects adolescents, neurons die as a result of the accumulation of glycogen—chains of glucose. They went on to propose that this accumulation is the root cause of this disease.

The breakthrough of this paper was two-sided: first, the researchers established a possible cause of LD and therefore ...

UCSB study reveals evolution at work

2014-02-27

New research by UC Santa Barbara's Kenneth S. Kosik, Harriman Professor of Neuroscience, reveals some very unique evolutionary innovations in the primate brain.

In a study published online today in the journal Neuron, Kosik and colleagues describe the role of microRNAs — so named because they contain only 22 nucleotides — in a portion of the brain called the outer subventricular zone (OSVZ). These microRNAs belong to a special category of noncoding genes, which prevent the formation of proteins.

"It's microRNAs that provide the wiring diagram, dictating which genes ...

Big step for next-generation fuel cells and electrolyzers

2014-02-27

A big step in the development of next-generation fuel cells and water-alkali electrolyzers has been achieved with the discovery of a new class of bimetallic nanocatalysts that are an order of magnitude higher in activity than the target set by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) for 2017. The new catalysts, hollow polyhedral nanoframes of platinum and nickel, feature a three-dimensional catalytic surface activity that makes them significantly more efficient and far less expensive than the best platinum catalysts used in today's fuel cells and alkaline electrolyzers. This ...

Fossilized human feces from 14th century contain antibiotic resistance genes

2014-02-27

A team of French investigators has discovered viruses containing genes for antibiotic resistance in a fossilized fecal sample from 14th century Belgium, long before antibiotics were used in medicine. They publish their findings ahead of print in the journal Applied and Environmental Microbiology.

"This is the first paper to analyze an ancient DNA viral metagenome," says Rebecca Vega Thurber of Oregon State University, Corvallis, who was not involved in the research.

The viruses in the fecal sample are phages, which are viruses that infect bacteria, rather than infecting ...

Physicians' stethoscopes more contaminated than palms of their hands

2014-02-27

VIDEO:

A comparative analysis shows that stethoscope diaphragms are more contaminated than the physician's own thenar eminence (group of muscles in the palm of the hand) following a physical examination.

Click here for more information.

Rochester, MN, February 27, 2014 – Although healthcare workers' hands are the main source of bacterial transmission in hospitals, physicians' stethoscopes appear to play a role. To explore this question, investigators at the University of ...

Study reveals mechanisms cancer cells use to establish metastatic brain tumors

2014-02-27

NEW YORK, NY, February 27, 2014 — New research from Memorial Sloan Kettering provides fresh insight into the biologic mechanisms that individual cancer cells use to metastasize to the brain. Published in the February 27 issue of Cell, the study found that tumor cells that reach the brain — and successfully grow into new tumors — hug capillaries and express specific proteins that overcome the brain's natural defense against metastatic invasion.

Metastasis, the process that allows some cancer cells to break off from their tumor of origin and take root in a different tissue, ...

Methane leaks from palm oil wastewater are a climate concern, CU-Boulder study says

2014-02-27

In recent years, palm oil production has come under fire from environmentalists concerned about the deforestation of land in the tropics to make way for new palm plantations. Now there is a new reason to be concerned about palm oil's environmental impact, according to researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder.

An analysis published Feb. 26 in the journal Nature Climate Change shows that the wastewater produced during the processing of palm oil is a significant source of heat-trapping methane in the atmosphere. But the researchers also present a possible solution: ...

Famed Milwaukee County Zoo orangutan's death caused by strange infection

2014-02-27

MADISON – Mahal, the young orangutan who became a star of the Milwaukee County Zoo and an emblem of survival for a dwindling species, led an extraordinary life.

It turns out, the young ape died an extraordinary death, too.

Rejected by his biological mother at the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo in Colorado Springs, Colo., and eventually flown to Milwaukee aboard a private jet to live with a surrogate mother, Mahal became one of the Milwaukee County Zoo's star attractions. His unexpected death at age 5 in late December 2012 was a shock to the community that came to know him through ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

[Press-News.org] Scientists uncover trigger for most common form of intellectual disability and autismFinding may explain many brain disorders, lead to prevention and treatment