(Press-News.org) STANFORD, Calif. — Whole-genome sequencing has been touted as a game-changer in personalized medicine. Clinicians can identify increases in disease risk for specific patients, as well as their responsiveness to certain drugs, by determining the sequence of the billions of building blocks, called nucleotides, that make up their DNA.

Now, researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have discovered that although life-changing discoveries can be made, significant challenges must be overcome before whole-genome sequencing can be routinely clinically useful. In particular, they found that individual risk determination would benefit from a degree of improved sequencing accuracy in disease-associated genes. Furthermore, up to 100 hours of manual assessment by professional genetic counselors or informatics specialists is required for detailed genome analysis.

Although the technique was once prohibitively expensive, plummeting costs have been widely expected to rapidly usher whole-genome sequencing into the arena of mainstream health care. However, the researchers' findings indicate that clinical advances from whole-genome sequencing are, at least in the near future, likely to be significantly more expensive and labor-intensive than some patients and clinicians may have been led to believe.

"We need to be very honest about what we can and cannot do at this point in time," said Euan Ashley, MD, associate professor of medicine and of genetics, one of three senior authors of the paper. "It's clear that if we sequence enough cases, we can change someone's life. But with this opportunity comes the responsibility to do this right. Our hope is that the identification of specific hurdles will allow researchers in this field to focus their efforts on overcoming them to make this technique clinically useful."

The paper will be published March 12 in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Michael Snyder, PhD, professor and chair of genetics, and Thomas Quertermous, MD, professor of medicine, also share senior authorship of the paper. Postdoctoral scholar and cardiology fellow Frederick Dewey, MD, genetic counselor Megan Grove, CGC, and postdoctoral scholar Cuiping Pan, PhD, share lead authorship of the paper.

The researchers analyzed the whole genomes of 12 healthy people and took note of the degree of sequencing accuracy necessary to make clinical decisions in individuals, the time it took to manually analyze each person's results and the projected costs of recommended follow-up medical tests.

"This has been an important project for the Stanford team for a number of reasons, not the least of which is that it represents the initial genetics effort to make use of the Stanford GenePool Biobank," said Quertermous, the William G. Irwin Professor in Cardiovascular Medicine. GenePool was recently launched to promote genomic research in a clinical setting and to improve patient care; the 12 people in the study were the first participants in the effort.

"GenePool gives Stanford patients the opportunity to participate in ground-breaking research and is a great opportunity for collaboration among Stanford translational researchers," Quertermous said.

The researchers estimated a cost of about $17,000 per person to sequence the genome and interpret and analyze the average of nearly 100 genetic variations deemed important enough for follow-up in each person. Each variation required approximately one hour of investigation to assess the relevant scientific literature and determine whether the change was indeed likely to modify disease risk in the individual. After this process, the researchers were left with approximately two to six results they felt could be clinically important; doctors who reviewed the results as part of the study suggested follow-up tests that carried costs of less than $1,000 per person.

In one of the 12 cases, however, the payoff of this intensive process was big: A woman with no family history of breast or ovarian cancer learned she carried a potentially deadly deletion in her BRCA1 gene. After confirmation of the finding in a clinical cancer genetics setting, she was able to take action to reduce her future risk for breast and ovarian cancer.

"Although there are clearly challenges in bringing whole-genome sequencing into the clinic, this finding was clearly medically significant," Dewey said. "It's not possible to predict from a study of 12 people how often this type of clinically actionable discovery will occur, but it definitely supports the use of this technology."

One significant challenge is the need to decisively determine the sequence of genes already known to be associated with disease. Dewey and his colleagues found that commercially available whole-genome sequencing does not achieve the accuracy necessary to identify every nucleotide in about 7 to 16 percent of genes known to be associated with increased disease risk. While a degree of uncertainty is allowable during studies of populations, which look for trends by comparing hundreds of genomes, it makes it impossible to make accurate predictions about one individual's health status.

"These off-the-shelf genome sequencing techniques were developed to provide generally good coverage of most of the genome," Dewey said. "But there are some regions that remain to be covered well that we care very deeply about. We still need to supplement this information with additional sequencing in some regions to make clinically usable decisions."

The study may affect a recent recommendation by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics that so-called "incidental findings," a term used to describe the discovery of potentially disease-associated variations identified during sequencing conducted for an unrelated medical reason, be routinely reported to an individual. Uncertainties or inaccuracies in the sequences of the 56 genes identified by the college could either give the appearance that a dangerous variation is normal, or cause unnecessary alarm and follow-up tests if a gene is mistakenly deemed to have a dangerous mutation.

In particular, the two sequencing technologies used in the study — one from San Diego-based Illumina Inc. and one from Mountain View-based Complete Genomics Inc. — had difficulty in reliably identifying regions of the genome with small insertions or deletions of nucleotides. These types of changes are particularly important because they can cause the abrupt termination of a protein coding sequence within the DNA.

"It's ironic, and slightly sobering, that we struggle the most in identifying insertions and deletions — those changes in the genome that are most impactful," Ashley said.

Once the sequences have been determined, it's necessary to figure out which changes, or variants, are likely to be important. Dewey and his colleagues found that the amount of manual labor involved in sifting through the many variants in each individual approached 100 hours. That's because, with the exception of a few well-known mutations, there is no standard way to assess the potential health impact of each change. In the study, three genetic counselors, three clinicians specializing in informatics and one medical pathologist examined each variant and assessed the relevant medical literature (including publications on animal and human studies, as well as genetic databases) to determine potential disease risk.

These challenges are particularly striking in the absence of a specific diagnostic question. "It remains significantly harder to use whole-genome sequencing for disease prediction than for disease diagnosis," said Dewey.

Variants expected to have potential health consequences were then shared with three primary care physicians and two medical geneticists, who independently studied the results and recommended possible follow-up tests for each person. In general, the projected costs for the tests were less than the researchers predicted — ranging from $351 to $776.

"Some experts in this field feel that this type of testing causes more harm than good, and may lead to very expensive follow-up tests," said Snyder, who is the Stanford W. Ascherman, MD, FACS, Professor in Genetics. "So it was interesting that costs were projected to be relatively modest."

Although some of the findings of the study are somewhat sobering, the authors are confident that the field of whole-genome sequencing is worth pursuing. Sequencing technology is evolving, and the National Institutes of Health-sponsored Clinical Genome Resource, or ClinGen, is meant to help speed the identification of clinically important variants and reduce the burden of manual investigation. Stanford professor of genetics Carlos Bustamante, PhD, is a co-principal investigator on a ClinGen project to improve predictions of disease-associated variants in a variety of populations.

"Our intention in doing this analysis was to draw a line describing where we are with this technology at this point in time and identify how best to move forward," Ashley said. "Things are becoming more clear, and the challenges to bringing this technique to the clinic are becoming crystallized. Whole-genome sequencing has the power to be absolutely transformative in the clinic."

INFORMATION:

Other Stanford authors involved in the research include genetic counselors Colleen Caleshu CGS, and Kerry Kingham, CGC; senior research scientist Hassan Chaib, PhD; clinical instructor Jason Merker, MD, PhD; graduate student Rachel Goldfeder; associate professor of pediatrics Greg Enns, MD; clinical associate professor of family and community medicine Sean David, MD, PhD; clinical assistant professor of medicine Neda Pakdaman, MD; professor of genetics Kelly Ormond, CGC; senior research scientist Teri Klein, PhD; assistant director of PharmGKB Michelle Whirl-Carrillo, PhD; clinical associate professor of medicine Kenneth Sakamoto, MD; instructor Matthew Wheeler, MD, PhD; associate professor of pediatrics Atul Butte, MD, PhD; associate professor of medicine James Ford, MD, PhD; professor of medicine Linda Boxer, MD; professor of medicine John Ioannidis, MD, PhD; professor of cardiology Alan Yeung, MD; professor of bioengineering, of genetics, and of medicine Russ Altman, MD, PhD; and assistant professor of medicine Themistocles Assimes, MD, PhD.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants HL094274-01A2, P50HG003389-05, R24GM61374, R01GM079719 9, U01HG004267-03 and DP2OD004613), the Breetwor Family Foundation and the LeDucq Foundation.

Dewey is a stockholder and member of the scientific advisory board of Personalis Inc, a privately held genome interpretation company, and he receives royalties for patented technology related to genome sequencing. Grove has speaker's fees from Illumina, Inc. Butte, Altman, Snyder and Ashley are founders, stockholders and members of the scientific advisory board of Personalis, and receive royalties for patents related to genome sequencing. Snyder is also a member of the scientific advisory board and stockholder of Genapsys Inc. Quertermous is a member of the scientific advisory board of Aviir Inc.

Information about Stanford's Departments of Genetics and of Medicine, which also supported the work, is available at http://genetics.stanford.edu and http://medicine.stanford.edu.

The Stanford University School of Medicine consistently ranks among the nation's top medical schools, integrating research, medical education, patient care and community service. For more news about the school, please visit http://mednews.stanford.edu. The medical school is part of Stanford Medicine, which includes Stanford Hospital & Clinics and Lucile Packard Children's Hospital Stanford. For information about all three, please visit http://stanfordmedicine.org/about/news.html.

Print media contact: Krista Conger at (650) 725-5371 (kristac@stanford.edu)

Broadcast media contact: Margarita Gallardo at (650) 723-7897 (mjgallardo@stanford.edu)

Whole-genome sequencing for clinical use faces many challenges, Stanford study finds

2014-03-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Giving dangerous employees socialization, close supervision can avoid problems

2014-03-11

Two UT Arlington management professors argue that employers can prevent workplace violence by keeping dangerous employees positively engaged and closely supervising them to ensure they get the help they need.

James Campbell Quick and M. Ann McFadyen of the College of Business management department analyzed FBI reports, case studies and human resource records to focus on the estimated 1 to 3 percent of employees prone to workplace acts of aggression, such as homicide, suicide or destruction of property.

The team advances the case for "mindfully observing" employees and ...

Long-term warming likely to be significant despite recent slowdown

2014-03-11

A new NASA study shows Earth's climate likely will continue to warm during this century on track with previous estimates, despite the recent slowdown in the rate of global warming.

This research hinges on a new and more detailed calculation of the sensitivity of Earth's climate to the factors that cause it to change, such as greenhouse gas emissions. Drew Shindell, a climatologist at NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York, found Earth is likely to experience roughly 20 percent more warming than estimates that were largely based on surface temperature observations ...

Acoustic cloaking device hides objects from sound

2014-03-11

VIDEO:

This video demonstrates the difference in how sound waves act with and without the acoustic cloak in their path. The red and blue lines represent the high and low points...

Click here for more information.

DURHAM, N.C. -- Using little more than a few perforated sheets of plastic and a staggering amount of number crunching, Duke engineers have demonstrated the world's first three-dimensional acoustic cloak. The new device reroutes sound waves to create the impression that ...

Scientists 'herd' cells in new approach to tissue engineering

2014-03-11

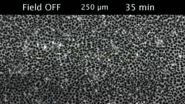

VIDEO:

Videos show the effect of electric fields on the movement of epithelial cells. The first clip shows the cells migrating normally until the electric field is turned on, causing the...

Click here for more information.

Berkeley -- Sometimes it only takes a quick jolt of electricity to get a swarm of cells moving in the right direction.

Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, found that an electrical current can be used to orchestrate the flow of a group ...

Prosocial youth less likely to associate with deviant peers, engage in problem behaviors

2014-03-11

COLUMBIA, Mo. – Prosocial behaviors, or actions intended to help others, remain an important area of focus for researchers interested in factors that reduce violence and other behavioral problems in youth. However, little is known regarding the connection between prosocial and antisocial behaviors. A new study by a University of Missouri human development expert found that prosocial behaviors can prevent youth from associating with deviant peers, thereby making the youth less likely to exhibit antisocial or problem behaviors, such as aggression and delinquency.

"This ...

Finding hiding place of virus could lead to new treatments

2014-03-11

WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. – March 11, 2014 – Discovering where a common virus hides in the body has been a long-term quest for scientists. Up to 80 percent of adults harbor the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), which can cause severe illness and death in people with weakened immune systems.

Now, researchers at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center's Institute for Regenerative Medicine report that stem cells that encircle blood vessels can be a hiding place, suggesting a potential treatment target.

In the American Journal of Transplantation (online ahead of print), senior scientist ...

First human totally endoscopic aortic valve replacements reported

2014-03-11

Beverly, MA, March 11, 2014 – Surgeons in France have successfully replaced the aortic valve in two patients without opening the chest during surgery. The procedure, using totally endoscopic aortic valve replacement (TEAVR), shows potential for improving quality of life of heart patients by offering significantly reduced chest trauma. It is described in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, an official publication of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

Endoscopic surgery is already used by cardiovascular surgeons for procedures such as atrial ...

No one likes a copycat, no matter where you live

2014-03-11

VIDEO:

One puppet peeks at another puppet's drawing because he can't decide what to draw, but he then draws a unique picture.

Click here for more information.

Even very young children understand what it means to steal a physical object, yet it appears to take them another couple of years to understand what it means to steal an idea.

University of Washington psychologist Kristina Olson and colleagues from Yale and the University of Pennsylvania discovered that preschoolers ...

Global survey of urban birds and plants find more diversity than expected

2014-03-11

AMHERST, Mass. – The largest analysis to date of the effect of urbanization on bird and plant species diversity worldwide confirms that while human influences such as land cover are more important drivers of species diversity in cities than geography or climate, many cities retain high numbers of native species and are far from barren environments.

Urban ecologist Paige Warren of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, co-leader of a 24-member research working group at the University of California Santa Barbara's National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis ...

Diets high in animal protein may help prevent functional decline in elderly individuals

2014-03-11

A diet high in protein, particularly animal protein, may help elderly individuals function at higher levels physically, psychologically, and socially, according to a study published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society.

Due to increasing life expectancies in many countries, increasing numbers of elderly people are living with functional decline, such as declines in cognitive ability and activities of daily living. Functional decline can have profound effects on health and the economy.

Research suggests that aging may reduce the body's ability to absorb or ...