(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (March 27, 2014) – Mitochondria, long known as "cellular power plants" for their generation of the key energy source adenosine triphosphate (ATP), are essential for proper cellular functions. Mitochondrial defects are often observed in a variety of diseases, including cancer, Alzheimer's disease, and Parkinson's disease, and are the hallmarks of a number of genetic mitochondrial disorders whose manifestations range from muscle weakness to organ failure. Despite a fairly strong understanding of the pathology of such genetic mitochondrial disorders, efforts to treat them have been largely ineffective.

But now, graduate student Walter Chen and postdoctoral researcher Kivanc Birsoy, both part of Whitehead Institute Member David Sabatini's lab, have unraveled how to rescue cells suffering from mitochondrial dysfunction, a finding that may lead to new therapies for this condition.

To find genetic mutations that would rescue the cells, Chen and Birsoy mimicked mitochondrial dysfunction in a haploid genetic system developed by former Whitehead Fellow Thijn Brummelkamp. After suppressing mitochondrial function using the drug antimycin, Chen and Birsoy saw that cells with mutations inactivating the gene ATPIF1 were protected against loss of mitochondrial function.

ATPIF1 is part of a backup system to save starving cells. When cells are deprived of oxygen and sugars, a mitochondrial complex that usually produces ATP, called ATP synthase, switches to consuming it, a state that can be harmful to an already starving cell. ATPIF1 interacts with ATP synthase to shut it down and prevent it from consuming the mitochondrion's dwindling ATP supply but, in the process, also worsens the mitochondrion's membrane potential

"In these diseases of mitochondrial dysfunction, in a sense, it's a false starvation situation for the cell—there are plenty of nutrients, but because there's a block in the mitochondria's normal function, the mitochondria behave as if there's not enough oxygen," says Chen, who with Birsoy, authored a paper in the journal Cell Reports describing this work. "So in these situations, activation of ATPIF1 is not good, because there are still many nutrients around to provide ATP. Instead, blocking ATPIF1 is therapeutic because it allows for maintenance of the membrane potential."

Liver cells are frequently affected in patients with severe mitochondrial disease, so Chen and Birsoy tested the effects of mitochondrial dysfunction in the liver cells of control mice and mice with ATPIF1 genetically knocked out. Again, the liver cells with suppressed ATPIF1 function dealt better with mitochondrial dysfunction than liver cells with normal ATPIF1 activity.

"It's very simple—if you get rid of ATPIF1, you survive in the presence of mitochondrial dysfunction," says Birsoy. "From what we see so far, there are no major side effects from blocking ATPIF1 in mice."

For Chen and Birsoy, the next step in this line of research is to test the effects of ATPIF1 suppression in mouse models of mitochondrial dysfunction. Then they will try to identify therapeutics that effectively block ATPIF1 function.

INFORMATION:

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health (CA103866, CA129105, and AI07389), David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, Alexander and Margaret Stewart Trust Fund, National Institute of Aging, Jane Coffin Childs Memorial Fund, Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, and Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation.

Written by Nicole Giese Rura

David Sabatini's primary affiliation is with Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, where his laboratory is located and all his research is conducted. He is also a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator and a professor of biology at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Full Citation:

"Inhibition of ATPIF1 Ameliorates Severe Mitochondrial Respiratory Chain Dysfunction in Mammalian Cells"

Cell Reports, April 10, 2014.

Walter W. Chen (1,2,3,4,9), Kıvanç Birsoy (1,2,3,4,9), Maria M. Mihaylova (1,2,3,4), Harriet Snitkin (6), Iwona Stasinski (6), Burcu Yucel (1,2,3,4), Erol C. Bayraktar (1,2,3,4), Jan E. Carette (7), Clary B. Clish (3), Thijn R. Brummelkamp (8), David D. Sabatini (6), and David M. Sabatini (1,2,3,4,5).

1. Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, 9 Cambridge Center, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA

2. Department of Biology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, MA 02139, USA

3. Broad Institute, Seven Cambridge Center, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA

4. David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at MIT, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA

5. Howard Hughes Medical Institute, MIT, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA

6. Department of Cell Biology, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY 10016, USA

7. Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA 94305, USA

8. Department of Biochemistry, Netherlands Cancer Institute, Plesmanlaan 121 1066 CX, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

9. These authors contributed equally to this work

Scientists find potential target for treating mitochondrial disorders

2014-03-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

In mapping feat, Scripps Florida scientists pinpoint neurons where select memories grow

2014-03-27

JUPITER, FL – March 27, 2014 – Memories are difficult to produce, often fragile, and dependent on any number of factors—including changes to various types of nerves. In the common fruit fly—a scientific doppelganger used to study human memory formation—these changes take place in multiple parts of the insect brain.

Scientists from the Florida campus of The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have been able to pinpoint a handful of neurons where certain types of memory formation occur, a mapping feat that one day could help scientists predict disease-damaged neurons in humans ...

Foraging bats can warn each other away from their dinners

2014-03-27

VIDEO:

In this animated graphic of bats' calls in flight, two bats are represented by different colors, red and blue. The bats' movements and vocalizations have been slowed by a factor...

Click here for more information.

Look into the spring sky at dusk and you may see flitting groups of bats, gobbling up insect meals in an intricately choreographed aerial dance. It's well known that echolocation calls keep the bats from hitting trees and each other. But now scientists have learned ...

Researchers at IRB discover a key regulator of colon cancer

2014-03-27

Barcelona, Thursday 27 March 2014.- A team headed by Angel R. Nebreda at the Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB) identifies a dual role of the p38 protein in colon cancer. The study demonstrates that, on the one hand, p38 is important for the optimal maintenance of the epithelial barrier that protects the intestine against toxic agents, thus contributing to decreased tumour development. Intriguingly, on the other hand, once a tumour has formed, p38 is required for the survival and proliferation of colon cancer cells, thus favouring tumour growth. The study is published ...

Researchers: Biomarkers predict effectiveness of radiation treatments for cancer

2014-03-27

An international team of researchers, led by Beaumont Health System's Jan Akervall, M.D., Ph.D., looked at biomarkers to determine the effectiveness of radiation treatments for patients with squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. They identified two markers that were good at predicting a patient's resistance to radiation therapy. Their findings were published in the February issue of the European Journal of Cancer.

Explains Dr. Akervall, co-director, Head and Neck Cancer Multidisciplinary Clinic, Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak, and clinical director of Beaumont's BioBank, ...

Cancer researchers find key protein link

2014-03-27

HOUSTON – (March 27, 2014) – A new understanding of proteins at the nexus of a cell's decision to survive or die has implications for researchers who study cancer and age-related diseases, according to biophysicists at the Rice University-based Center for Theoretical Biological Physics (CTBP).

Experiments and computer analysis of two key proteins revealed a previously unknown binding interface that could be addressed by medication. Results of the research appear this week in an open-source paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The proteins ...

Sleep may stop chronic pain sufferers from becoming 'zombies'

2014-03-27

Chronic pain sufferers could be kept physically active by improving the quality of their sleep, new research suggests.

The study by the University of Warwick's Department of Psychology, published in PLoS One, found that sleep was a worthy target for treating chronic pain and not only as an answer to pain-related insomnia.

"Engaging in physical activity is a key treatment process in pain management. Very often, clinicians would prescribe exercise classes, physiotherapy, walking and cycling programmes as part of the treatment, but who would like to engage in these activities ...

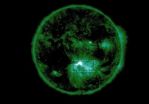

First sightings of solar flare phenomena confirm 3-D models of space weather

2014-03-27

Scientists have for the first time witnessed the mechanism behind explosive energy releases in the Sun's atmosphere, confirming new theories about how solar flares are created.

New footage put together by an international team led by University of Cambridge researchers shows how entangled magnetic field lines looping from the Sun's surface slip around each other and lead to an eruption 35 times the size of the Earth and an explosive release of magnetic energy into space.

The discoveries of a gigantic energy build-up bring us a step closer to predicting when and where ...

Corporate layoff strategies are increasing workplace gender and racial inequality

2014-03-27

Research from Prof. Alexandra Kalev of Tel Aviv University's Department of Sociology and Anthropology reveals that current workplace downsizing policies are reducing managerial diversity and increasing racial and gender inequalities. According to the study, layoff practices focusing on positions and tenure, rather than worker performance, minimized the share of white women in management positions by 25 percent and of black men by 20 percent. Prof. Kalev found that a striking two-thirds of the companies surveyed used tenure or position as their core criteria for downsizing. ...

Instituting a culture of professionalism

2014-03-27

Boston, MA—There is a growing recognition that in health care institutions where professionalism is not embraced and expectations of acceptable behaviors are not clear and enforced, an increase in medical errors and adverse events and a deterioration in safe working conditions can occur. In 2008 Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) created the Center for Professionalism and Peer Support (CPPS) and has seen tremendous success in this initiative. Researchers recently analyzed data from the CPPS from 2010 through 2013 and found that employees continue to turn to the center for ...

Controlling electron spins by light

2014-03-27

This news release is available in German.

The material class of topological insulators has been discovered a few years ago and displays amazing properties: In their inside, they behave electrically insulating but at their surface they form metallic, conducting states. The electron spin, i. e., their intrinsic angular momentum, is playing a decisive role. Their sense of rotation is directly coupled to their direction of movement. This coupling leads not only to a high stability of the metallic property but also enables a particularly lossless electrical conduction. ...