(Press-News.org) EAST LANSING, Mich. — What began 20 years ago as an innovation to improve paper industry processes and dairy forage digestibility may now open the door to a much more energy- and cost-efficient way to convert biomass into fuel.

The research, which appears in the current issue of Science, focuses on enhancing poplar trees so they can break down easier and thus improving their viability as a biofuel. The long-term efforts and teamwork involved to find this solution can be described as a rare, top-down approach to engineering plants for digestibility, said Curtis Wilkerson, Michigan State University plant biologist and the lead author.

"By designing poplars for deconstruction, we can improve the degradability of a very useful biomass product," said Wilkerson, Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center scientist. "Poplars are dense, easy to store and they flourish on marginal lands not suitable for food crops, making them a non-competing and sustainable source of biofuel."

The idea to engineer biomass for easier degradation first took shape in the mid-1990s in the lab of John Ralph, University of Wisconsin-Madison professor and GLBRC plants leader. Ralph's group was looking to reduce energy usage in the paper pulping process by more efficiently removing lignin – the polymer that gives plant cell walls their sturdiness – from trees. If weak bonds could be introduced into lignin, this hardy material could be "unzipped," making it much easier for chemical processes to break it down.

Ralph's approach had clear benefits for the biofuels industry as well. The difficulty in removing and processing lignin remains a major obstacle to accessing the valuable sugars contained within biomass, adding energy and cost to the production of biofuels. Seeing an opportunity to carry out Ralph's concept in poplar, GLBRC researchers pooled their expertise.

To produce the enhanced poplars, Wilkerson identified and isolated a gene capable of making monomers – molecular glue of sorts – with bonds that are easier to break apart. Next, Shawn Mansfield with the University of British Columbia successfully put that gene into poplars. The team then determined that the plants not only created the monomers but also incorporated them into the lignin polymer. This introduced weak links into the lignin backbone and transformed the poplars' natural lignin into a more easily degradable version.

"We can now move beyond tinkering with the known genes in the lignin pathway to using exotic genes to alter the lignin polymer in predesigned but plant-compatible ways," Ralph said. "This approach should pave the way to generating more valuable biomass that can be processed in a more energy efficient manner for biofuels and paper products."

The research also is noteworthy for being the direct result of a collaboration funded by the GLBRC, funded by the U.S. Department of Energy and created to make transformational breakthroughs in new cellulosic biofuels technology. Realizing the collaborative project called for a wide array of expertise, from finding the gene and introducing it into the plants, to proving, via newly designed analyses, that the plant was utilizing the new monomers in making its lignin.

"I guarantee that John Ralph and I would never have met without the GLBRC," Wilkerson said. "When I first met him at a group retreat, I knew very little about lignin. But I ended up sharing some techniques I'd been using for totally different projects that I thought might be useful for his 'zip-lignin' research. The collaboration really grew from there."

INFORMATION:

Michigan State University has been working to advance the common good in uncommon ways for more than 150 years. One of the top research universities in the world, MSU focuses its vast resources on creating solutions to some of the world's most pressing challenges, while providing life-changing opportunities to a diverse and inclusive academic community through more than 200 programs of study in 17 degree-granting colleges.

For MSU news on the Web, go to MSUToday. Follow MSU News on Twitter at twitter.com/MSUnews.

'Unzipping' poplars' biofuel potential

2014-04-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study shows more than half of high-risk alcohol users report improvement after surgery

2014-04-03

BOSTON – Much has been reported about the potential for increased risk of alcohol misuse after weight loss surgery (WLS), with most theories pointing to lower alcohol tolerance and a longer time to return to a sober state after surgery, but a new study from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center suggests that upwards of half of high-risk drinkers are actually less likely to report high-risk drinking behavior after weight loss surgery.

The results appear in the journal, Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases.

"This is the first study to show that high-risk drinking ...

Aging workforce requires new strategies for employee retention, MU researcher says

2014-04-03

COLUMBIA, Mo. – As more baby boomers reach retirement age, state governments face the likelihood of higher workforce turnover. For example, in the state of Missouri, more than 25 percent of all active state employees will be eligible to retire by 2016. Such large numbers of retirees threaten the continuity, membership and institutional histories of the state government workforce, according to Angela Curl, assistant professor in the University of Missouri School of Social Work. In a case study of the state of Missouri's Deferred Retirement Option Provision (BackDROP), Curl ...

Scientists say new computer model amounts to a lot more than a hill of beans

2014-04-03

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Crops that produce more while using less water seem like a dream for a world with a burgeoning population and already strained food and water resources. This dream is coming closer to reality for University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign researchers who have developed a new computer model that can help plant scientists breed better soybean crops.

Under current climate conditions, the model predicts a design for a soybean crop with 8.5 percent more productivity, but using 13 percent less water, and reflecting 34 percent more radiation back into space, ...

Dress and behavior of mass shooters as factors to predict and prevent future attacks

2014-04-03

New Rochelle, NY, April 3, 2014–In many recent incidents of premeditated mass shooting the perpetrators have been male and dressed in black, and may share other characteristics that could be used to identify potential shooters before they commit acts of mass violence. Risk factors related to the antihero, dark-knight persona adopted by these individuals are explored in an article in Violence and Gender, a new peer-reviewed journal from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers. The article is available free on the Violence and Gender website at http://www.liebertpub.com/vio.

In ...

Ouch! Computer system spots fake expressions of pain better than people

2014-04-03

BUFFALO, N.Y. — A joint study by researchers at the University of California, San Diego, the University at Buffalo, and the University of Toronto has found that a computer–vision system can distinguish between real or faked expressions of pain more accurately than can humans.

This ability has obvious uses for uncovering pain malingering — fabricating or exaggerating the symptoms of pain for a variety of motives — but the system also could be used to detect deceptive actions in the realms of security, psychopathology, job screening, medicine and law.

The study, "Automatic ...

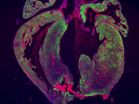

New study casts doubt on heart regeneration in mammals

2014-04-03

The mammalian heart has generally been considered to lack the ability to repair itself after injury, but a 2011 study in newborn mice challenged this view, providing evidence for complete regeneration after resection of 10% of the apex, the lowest part of the heart. In a study published by Cell Press in Stem Cell Reports on April 3, 2014, researchers attempted to replicate these recent findings but failed to uncover any evidence of complete heart regeneration in newborn mice that underwent apex resection.

"Our results question the usefulness of the apex resection model ...

Hummingbirds' 22-million-year-old history of remarkable change is far from complete

2014-04-03

The first comprehensive map of hummingbirds' 22-million-year-old family tree—reconstructed based on careful analysis of 284 of the world's 338 known species—tells a story of rapid and ongoing diversification. The decade-long study reported in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on April 3 also helps to explain how today's hummingbirds came to live where they do.

Part of the secret to the birds' remarkable success lies in the formation of nine principal groups or clades, hummingbirds' unique relationship to flowering plants, and the birds' continued spread into new ...

Lactase persistence alleles reveal ancestry of southern African Khoe pastoralists

2014-04-03

In a new study a team of researchers lead from Uppsala University show how lactase persistence variants tell the story about the ancestry of the Khoe people in southern Africa. The team concludes that pastoralist practices were brought to southern Africa by a small group of migrants from eastern Africa. The study is published in Current Biology today.

"This is really an exciting time for African genetics. Up until now, routes of human migration in Africa were inferred mostly based on linguistics and archaeology, now we can use genetics to test these hypotheses." says ...

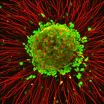

Cancer and the Goldilocks effect

2014-04-03

Researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have found that too little or too much of an enzyme called SRPK1 promotes cancer by disrupting a regulatory event critical for many fundamental cellular processes, including proliferation.

The findings are published in the current online issue of Molecular Cell.

The family of SRPK kinases was first discovered by Xiang-Dong Fu, PhD, professor in the Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine at UC San Diego in 1994. In 2012, Fu and colleagues uncovered that SPRK1 was a key signal transducer ...

Study helps unravel the tangled origin of ALS

2014-04-03

MADISON, Wis. — By studying nerve cells that originated in patients with a severe neurological disease, a University of Wisconsin-Madison researcher has pinpointed an error in protein formation that could be the root of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Also called Lou Gehrig's disease, ALS causes paralysis and death. According to the ALS Association, as many as 30,000 Americans are living with ALS.

After a genetic mutation was discovered in a small group of ALS patients, scientists transferred that gene to animals and began to search for drugs that might treat those ...