(Press-News.org) Climate feedbacks from decomposition by soil microbes are one of the biggest uncertainties facing climate modelers. A new study from the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) and the University of Vienna shows that these feedbacks may be less dire than previously thought.

The dynamics among soil microbes allow them to work more efficiently and flexibly as they break down organic matter – spewing less carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than previously thought, according to a new study published in the journal Ecology Letters.

"Previous climate models had simply looked at soil microbes as a black box," says Christina Kaiser, lead author of the study who conducted the work as a post-doctoral researcher at IIASA. Kaiser, now an assistant professor at the University of Vienna, developed an innovative model that helps bring these microbial processes to light.

Microbes and the climate

"Soil microbes are responsible for one of the largest carbon dioxide emissions on the planet, about six times higher than from fossil fuel burning," says IIASA researcher Oskar Franklin, one of the study co-authors. These microbes release greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere as they decompose organic matter. At the same time, the Earth's trees and other plants remove about the same amount of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through photosynthesis.

As long as these two fluxes remain balanced, everything is fine.

But as the temperature warms, soil conditions change and decomposition may change. And previous models of soil decomposition suggest that nutrient imbalances such as nitrogen deficiency would lead to increased carbon emissions. "This is such a big flux that even small changes could have a large effect," says Kaiser. "The potential feedback effects are considerably high and difficult to predict."

Diversity does the trick

How exactly microorganisms in the soil and litter react to changing conditions, however, remains unclear. One reason is that soil microbes live in diverse, complex communities, where they interact with each other and rely on one another for breaking down organic matter.

"One microbe species by itself might not be able to break down a complex substrate like a dead leaf," says Kaiser. "How this system reacts to changes in the environment doesn't depend just on the individual microbes, but rather on the changes to the numbers and interactions of microbe species within the soil community."

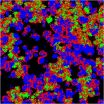

To understand these community processes, Kaiser and colleagues developed a computer model that can simulate complex soil dynamics. The model simulates the interactions between 10,000 individual microbes within a 1mm by 1mm square. It shows how nutrients, which influence microbial metabolism, affect these interactions, and change the soil community and thereby the decomposition process.

Previous models had viewed soil decomposition as a single process, and assumed that nutrient imbalances would lead to less efficient decomposition and hence greater greenhouse gas emissions. But the new study shows that, in fact, microbial communities reorganize themselves and continue operating efficiently – emitting far less carbon dioxide than previously predicted.

"Our analyses highlight how the systems thinking for which IIASA is renowned advances insights into key ecosystem services," says study co-author and IIASA ecologist Ulf Dieckmann.

"This model is a huge step forward in our understanding of microbial decomposition, and provides us with a much clearer picture of the soil system," says University of Vienna ecologist Andreas Richter, another study co-author.

INFORMATION:

Reference

Kaiser C, Franklin O, Dieckmann U, and Richter A. 2014. Microbial community dynamics alleviate stoichiometric constraints during litter decay. Ecology Letters. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ele.12269/abstract

For more information please contact:

Christina Kaiser

University of Vienna

Department of Microbiology and Ecosystem Science

Tel: +43 (0)1 4277 76663

Mob: +43 6503773428

christina.kaiser@univie.ac.at

Oskar Franklin

Research Scholar

Ecosystems Services and Management

+43(0) 2236 807 251

franklin@iiasa.ac.at

About IIASA:

IIASA is an international scientific institute that conducts research into the critical issues of global environmental, economic, technological, and social change that we face in the twenty-first century. Our findings provide valuable options to policy makers to shape the future of our changing world. IIASA is independent and funded by scientific institutions in Africa, the Americas, Asia, Oceania, and Europe. http://www.iiasa.ac.at

The tiniest greenhouse gas emitters

2014-04-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Exploring the genetics of 'I'll do it tomorrow'

2014-04-07

Procrastination and impulsivity are genetically linked, suggesting that the two traits stem from similar evolutionary origins, according to research published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science. The research indicates that the traits are related to our ability to successfully pursue and juggle goals.

"Everyone procrastinates at least sometimes, but we wanted to explore why some people procrastinate more than others and why procrastinators seem more likely to make rash actions and act without thinking," explains psychological ...

Green tea boosts your brain

2014-04-07

Green tea is said to have many putative positive effects on health. Now, researchers at the University of Basel are reporting first evidence that green tea extract enhances the cognitive functions, in particular the working memory. The Swiss findings suggest promising clinical implications for the treatment of cognitive impairments in psychiatric disorders such as dementia. The academic journal Psychopharmacology has published their results.

In the past the main ingredients of green tea have been thoroughly studied in cancer research. Recently, scientists have also been ...

New method for prostate cancer detection can save millions of men painful examination

2014-04-07

Each year prostate tissue samples are taken from over a million men around the world – in most cases using 12 large biopsy needles – to check whether they have prostate cancer. This medical procedure, which was recently described by an American urology professor as 'barbaric'**, shows that 70% of the subjects do not have cancer. The examination is unnecessarily painful and involves risk for these patients, and it is also costly to carry out. A patient-friendly examination, which drastically reduces the need for biopsies, and may even eliminate them altogether, has been ...

Rilpivirine combination product in pretreated HIV-1 patients: added benefit not proven

2014-04-07

The German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG) reassessed the antiviral drug combination rilpivirine/emtricitabine/tenofovir. In early 2012, the combination was approved for the treatment of adults infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) who have not received previous antiretroviral treatment. For men, the Institute then found proof, and for women, indications of a considerable added benefit of the fixed combination in comparison with the appropriate comparator therapy.

In the end of 2013, the approval was expanded to people ...

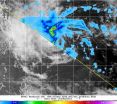

Tropical Cyclone Peipah passes Palau, Philippines prepare

2014-04-07

Tropical Cyclone Peipah passed the island of Palau on April 5 moving through the Northwestern Pacific Ocean as it heads for a landfall in the Philippines. Peipah was formerly known as Tropical Cyclone 05W and was renamed when it reached tropical storm-force. Since then, however, wind shear has weakened the storm to a tropical depression.

On April 5 at 2100 UTC/5 p.m. EDT, Tropical Storm 05W, renamed Peipah (and known locally in the Philippines as Domeng) was located about 262 nautical miles east-southeast of Koror. It was centered near 5.5 north and 137.8 east and moving ...

Cleft palate discovery in dogs to aid in understanding human birth defect

2014-04-07

UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine researchers have identified the genetic mutation responsible for a form of cleft palate in the dog breed Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retrievers.

They hope that the discovery, which provides the first dog model for the craniofacial defect, will lead to a better understanding of cleft palate in humans. Although cleft palate is one of the most common birth defects in children, affecting approximately one in 1,500 live human births in the United States, it is not completely understood.

The findings appear this week online in the journal ...

Remedial courses fail bachelor's degree seekers, but boost those in associate's programs

2014-04-07

CHESTNUT HILL, MA (April 7, 2014) – Taking remedial courses at the four-year college level may hold students back from earning their bachelor's degrees, but at the community college level remedial education can help earn an associate's degree, according to researchers from Boston College's Lynch School of Education.

The role of remedial education has been under scrutiny for years, viewed as an essential tool in efforts to raise rates of degree completion. At the same time, critics question whether the courses are appropriate for institutions of higher education.

The ...

Movies synchronize brains

2014-04-07

When we watch a movie, our brains react to it immediately in a way similar to brains of other people. Researchers at Aalto University in Finland have succeeded in developing a method fast enough to observe immediate changes in the function of the brain even when watching a movie.

By employing movies it was possible to investigate the function of the human brain in experimental conditions that are close to natural. Traditionally, in neuroscience research, simple stimuli, such as checkerboard patterns or single images, have been used.

Viewing a movie creates multilevel ...

Caffeine against Alzheimer's disease

2014-04-07

As part of a German-French research project, a team led by Dr. Christa E. Müller from the University of Bonn and Dr. David Blum from the University of Lille was able to demonstrate for the first time that caffeine has a positive effect on tau deposits in Alzheimer's disease. The two-years project was supported with 30,000 Euro from the non-profit Alzheimer Forschung Initiative e.V. (AFI) and with 50,000 Euro from the French Partner organization LECMA. The initial results were published in the online edition of the journal "Neurobiology of Aging."

Tau deposits, along ...

Hi-tech innovation gauges science learning in preschoolers

2014-04-07

Researchers are blending technology with nature, as they present details on an iPad application to examine how young children are learning science skills in nature-themed outdoor play settings. Alan Wight, a doctoral candidate in the University of Cincinnati School of Education; Cathy Maltbie, a research associate for the UC Evaluation Services Center; and Victoria Carr, a UC associate professor of education and director of the UC Arlitt Child and Family Research and Education Center, presented details on the innovation at the annual meeting of the American Educational ...