(Press-News.org) New research from North Carolina State University and UNC-Chapel Hill reveals that energy is transferred more efficiently inside of complex, three-dimensional organic solar cells when the donor molecules align face-on, rather than edge-on, relative to the acceptor. This finding may aid in the design and manufacture of more efficient and economically viable organic solar cell technology.

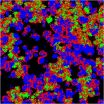

Organic solar cell efficiency depends upon the ease with which an exciton – the energy particle created when light is absorbed by the material – can find the interface between the donor and acceptor molecules within the cell. At the interface, the exciton is converted into charges that travel to the electrodes, creating power. While this sounds straightforward enough, the reality is that molecules within the donor and acceptor layers can mix, cluster into domains, or both, leading to variances in domain purity and size which can affect the power conversion process. Moreover, the donor and acceptor molecules have different shapes, and the way they are oriented relative to one another matters. This complexity makes it very difficult to measure the important characteristics of their structure.

NC State physicist Harald Ade, UNC-Chapel Hill chemist Wei You and collaborators from both institutions studied the molecular composition of solar cells in order to determine what aspects of the structures have the most impact on efficiency. In this project the team used advanced soft X-ray techniques to describe the orientation of molecules within the donor and acceptor materials. By manipulating this orientation in different solar cell polymers, they were able to show that a face-on alignment between donor and acceptor was much more efficient in generating power than an edge-on alignment.

"A face-on orientation is thought to allow favorable interactions for charge transfer and inhibit recombination, or charge loss, in organic solar cells," Ade says, "though precisely what happens on the molecular level is still unclear.

"Donor and acceptor layers don't just lie flat against each other," Ade explains. "There's a lot of mixing going on at the molecular level. Picture a bowl of flat pasta, like fettucine, as the donor polymer, and then add 'ground meat,' or a round acceptor molecule, and stir it all together. That's your solar cell. What we want to measure, and what matters in terms of efficiency, is whether the flat part of the fettuccine hugs the round pieces of meat – a face-on orientation – or if the fettuccine is more randomly oriented, or worst case, only the narrow edges of stacked up pasta touch the meat in an edge-on orientation. It's a complicated problem.

"This research gives us a method for measuring this molecular orientation, and will allow us to find out what the effects of orientation are and how orientation can be fine-tuned or controlled."

INFORMATION:

The paper appears online April 6 in Nature Photonics. Fellow NC State collaborators were John Tumbleston, Brian Collins, Eliot Gann, and Wei Ma. Liqiang Yang and Andrew Stuart from UNC-Chapel Hill also contributed to the work. The work was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Science, the Office of Naval Research, and the National Science Foundation.

Note to editors: Abstract of the paper follows.

"The influence of molecular orientation on organic bulk heterojunction solar cells"

Authors: John R. Tumbleston, Brian A. Collins, Eliot Gann, Wei Ma and Harald Ade, North Carolina State University; Liqiang Yang, Andrew C. Stuart and Wei You, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Published: April 6, 2014, in Nature Photonics

Abstract:

In bulk heterojunction organic photovoltaics, electron-donating and electron-accepting materials form a distributed network of heterointerfaces in the photoactive layer, where critical photo-physical processes occur. However, little is known about the structural properties of these interfaces due to their complex three-dimensional arrangement and the lack of techniques to measure local order. Here, we report that molecular orientation relative to donor/acceptor heterojunctions is an important parameter in realizing high-performance fullerene-based, bulk heterojunction solar cells. Using resonant soft X-ray scattering, we characterize the degree of molecular orientation, an order parameter that describes face-on (+1) or edge-on (-1) orientations relative to these heterointerfaces. By manipulating the degree of molecular orientation through the choice of molecular chemistry and the characteristics of the processing solvent, we are able to show the importance of this structural parameter on the performance of bulk heterojunction organic photovoltaic devices featuring the electron-donating polymers PNDT–DTBT, PBnDT–DTBT or PBnDT–TAZ.

Organic solar cells more efficient with molecules face-to-face

2014-04-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Switching off anxiety with light

2014-04-07

Receptors for the messenger molecule serotonin can be modified in such a way that they can be activated by light. Together with colleagues, neuroscientists from the Ruhr-Universität Bochum (RUB) report on this finding in the journal "Neuron". An imbalance in serotonin levels seems to cause anxiety and depression. The researchers have provided a new model system for investigating the mechanism underlying these dysfunctions in cell cultures as well as living organisms.

G protein coupled receptors play an important role in medicine and health

One receptor, which is important ...

The tiniest greenhouse gas emitters

2014-04-07

Climate feedbacks from decomposition by soil microbes are one of the biggest uncertainties facing climate modelers. A new study from the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) and the University of Vienna shows that these feedbacks may be less dire than previously thought.

The dynamics among soil microbes allow them to work more efficiently and flexibly as they break down organic matter – spewing less carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than previously thought, according to a new study published in the journal Ecology Letters.

"Previous climate ...

Exploring the genetics of 'I'll do it tomorrow'

2014-04-07

Procrastination and impulsivity are genetically linked, suggesting that the two traits stem from similar evolutionary origins, according to research published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science. The research indicates that the traits are related to our ability to successfully pursue and juggle goals.

"Everyone procrastinates at least sometimes, but we wanted to explore why some people procrastinate more than others and why procrastinators seem more likely to make rash actions and act without thinking," explains psychological ...

Green tea boosts your brain

2014-04-07

Green tea is said to have many putative positive effects on health. Now, researchers at the University of Basel are reporting first evidence that green tea extract enhances the cognitive functions, in particular the working memory. The Swiss findings suggest promising clinical implications for the treatment of cognitive impairments in psychiatric disorders such as dementia. The academic journal Psychopharmacology has published their results.

In the past the main ingredients of green tea have been thoroughly studied in cancer research. Recently, scientists have also been ...

New method for prostate cancer detection can save millions of men painful examination

2014-04-07

Each year prostate tissue samples are taken from over a million men around the world – in most cases using 12 large biopsy needles – to check whether they have prostate cancer. This medical procedure, which was recently described by an American urology professor as 'barbaric'**, shows that 70% of the subjects do not have cancer. The examination is unnecessarily painful and involves risk for these patients, and it is also costly to carry out. A patient-friendly examination, which drastically reduces the need for biopsies, and may even eliminate them altogether, has been ...

Rilpivirine combination product in pretreated HIV-1 patients: added benefit not proven

2014-04-07

The German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG) reassessed the antiviral drug combination rilpivirine/emtricitabine/tenofovir. In early 2012, the combination was approved for the treatment of adults infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) who have not received previous antiretroviral treatment. For men, the Institute then found proof, and for women, indications of a considerable added benefit of the fixed combination in comparison with the appropriate comparator therapy.

In the end of 2013, the approval was expanded to people ...

Tropical Cyclone Peipah passes Palau, Philippines prepare

2014-04-07

Tropical Cyclone Peipah passed the island of Palau on April 5 moving through the Northwestern Pacific Ocean as it heads for a landfall in the Philippines. Peipah was formerly known as Tropical Cyclone 05W and was renamed when it reached tropical storm-force. Since then, however, wind shear has weakened the storm to a tropical depression.

On April 5 at 2100 UTC/5 p.m. EDT, Tropical Storm 05W, renamed Peipah (and known locally in the Philippines as Domeng) was located about 262 nautical miles east-southeast of Koror. It was centered near 5.5 north and 137.8 east and moving ...

Cleft palate discovery in dogs to aid in understanding human birth defect

2014-04-07

UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine researchers have identified the genetic mutation responsible for a form of cleft palate in the dog breed Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retrievers.

They hope that the discovery, which provides the first dog model for the craniofacial defect, will lead to a better understanding of cleft palate in humans. Although cleft palate is one of the most common birth defects in children, affecting approximately one in 1,500 live human births in the United States, it is not completely understood.

The findings appear this week online in the journal ...

Remedial courses fail bachelor's degree seekers, but boost those in associate's programs

2014-04-07

CHESTNUT HILL, MA (April 7, 2014) – Taking remedial courses at the four-year college level may hold students back from earning their bachelor's degrees, but at the community college level remedial education can help earn an associate's degree, according to researchers from Boston College's Lynch School of Education.

The role of remedial education has been under scrutiny for years, viewed as an essential tool in efforts to raise rates of degree completion. At the same time, critics question whether the courses are appropriate for institutions of higher education.

The ...

Movies synchronize brains

2014-04-07

When we watch a movie, our brains react to it immediately in a way similar to brains of other people. Researchers at Aalto University in Finland have succeeded in developing a method fast enough to observe immediate changes in the function of the brain even when watching a movie.

By employing movies it was possible to investigate the function of the human brain in experimental conditions that are close to natural. Traditionally, in neuroscience research, simple stimuli, such as checkerboard patterns or single images, have been used.

Viewing a movie creates multilevel ...