(Press-News.org) T-cells are the body's sentinels, patrolling every corner of the body in search of foreign threats such as bacteria and viruses. Receptor molecules on the T-cells identify invaders by recognizing their specific antigens, helping the T-cells discriminate attackers from the body's own cells. When they recognize a threat, the T-cells signal other parts of the immune system to confront the invader.

These T-cells use a complex process to recognize the foreign pathogens and diseased cells. In a paper published this week in the journal Cell, researchers add a new level of understanding to that process by describing how the T-cell receptors (TCR) use mechanical contact – the forces involved in their binding to the antigens – to make decisions about whether or not the cells they encounter are threats.

"This is the first systematic study of how T-cell recognition is affected by mechanical force, and it shows that forces play an important role in the functions of T-cells," said Cheng Zhu, a Regents' professor in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory University. "We think that mechanical force plays a role in almost every step of T-cell biology."

The researchers, who were supported by the National Institutes of Health, made their discoveries using a tiny sensor based on a single red blood cell and a new technique for detecting calcium ions emitted by the T-cells as part of the signaling process. They independently studied the binding of antigens to more than a hundred individual T-cells, measuring the forces involved in the binding and the lifetimes of the bonds. That information was then correlated to the calcium signaling they observed.

Among the findings, the researchers learned that interactions between the TCRs and agonist peptide-major histocompatibility complexes (MHC) form catch bonds that become stronger with the application of additional force to initiate intracellular signaling. Less active MHC complexes form slip bonds that weaken with force and don't initiate signaling. Overall, they found that the signaling outcome of an interaction between an antigen and a TCR depends on the magnitude, duration, frequency and timing of the force application.

"Force adds another dimension to interactions with T-cells," Zhu explained. "Antigens that have a bond lifetime that is prolonged by force would have a higher likelihood of triggering signaling. Repeat engagements and lifetime accumulations play a role, and the decision to signal is usually made based on the accumulation of actions, not a single action."

He compared the force component of T-cell activation to multiple steps needed to enter a person's office inside a secured building. A key card and a personal identification number may first be necessary to enter the building, while an ordinary key might then be needed to get into a specific office. Requiring both recognition of an antigen and specific level of mechanical force may help the T-cell avoid activating when it shouldn't, Zhu said.

Zhu compared the accumulation of bonds to the punches that a boxer sustains during a fight. A rare very hard single punch, or a series of lesser blows over a short period of time, can both lead to a knockout. But a series of light blows over a longer time may have no effect, Zhu said.

Researchers already have other examples of how mechanical force can affect the operation of cellular systems. For instance, mechanical stress created by blood flow acting on the endothelial cells that line blood vessel walls plays a role in the disease atherosclerosis. Force is also necessary for proper bone growth and healing. That mechanical forces would also play a role in the immune system therefore isn't surprising, Zhu said.

"We now have a broader recognition that the physical environment and mechanical environment regulate many of the biological phenomena in the body," he said. "When you exert a force on the TCR bonds, some of them dissociate faster, while others come off more slowly. This has an effect on the response of the T-cell receptor."

In their experiments, Zhu and collaborators Baoyu Liu, Wei Chen and Brian Evavold used a biomembrane force probe to measure the strength and longevity of bonds between T cells and antigens. The probe consists, in part, of a red blood cell aspirated to a micropipette. Attached to the red blood cell is a bead on which researchers place the antigen under study. Using a delicate mechanism that precisely controls motion, the bead is then moved into contact with a T-cell receptor, allowing binding to take place.

To test the strength of bond formed between an antigen and the TCR, the researchers apply piconewton forces to separate the bead holding the antigen from the TCR. The red blood cell acts as a spring, stretching and allowing a measurement of the forces that must be applied to separate the TCR and antigen. The technique, which requires motion control at the nanometer scale, allows measurement of binding between the antigen and a single TCR.

To assess the impact of the binding on intracellular signaling, the researchers inject a dye into the cells that fluoresces when exposed to the calcium signaling ions. Detecting the fluorescence allowed the researchers to know when the mechanical force triggered T-cell signaling.

"We can directly look at kinetics and signaling at the same time," explained Liu, a research scientist in the Coulter Department and co-first author of the paper. "We can observe the signaling directly induced by TCR interactions."

As a next step, Zhu's team would like to explore the effects of force on development of T-cells using the new experimental techniques. Evidence suggests that the forces to which the cells are exposed while they are in a juvenile stage may affect the fates of their development.

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health through awards AI38282 and GM096187. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

CITATION: Baoyu Liu, Wei Chen, Brian D. Evavold and Cheng Zhu, "Accumulation of Dynamic Catch Bonds between TCR and Agonist Peptide-MHC Triggers T-Cell Signaling, " (Cell 2014).

Researchers determine how mechanical forces affect T-cell recognition and signaling

2014-04-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Researchers identify transcription factors distinguishing glioblastoma stem cells

2014-04-10

The activity of four transcription factors – proteins that regulate the expression of other genes – appears to distinguish the small proportion of glioblastoma cells responsible for the aggressiveness and treatment resistance of the deadly brain tumor. The findings by a team of Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) investigators, which will be published in the April 24 issue of Cell and are receiving advance online release, support the importance of epigenetics – processes controlling whether or not genes are expressed – in cancer pathology and identify molecular circuits ...

Yale researchers search for earliest roots of psychiatric disorders

2014-04-10

Newborns whose mothers were exposed during pregnancy to any one of a variety of environmental stressors — such as trauma, illness, and alcohol or drug abuse — become susceptible to various psychiatric disorders that frequently arise later in life. However, it has been unclear how these stressors affect the cells of the developing brain prenatally and give rise to conditions such as schizophrenia, post-traumatic stress disorder, and some forms of autism and bipolar disorders.

Now, Yale University researchers have identified a single molecular mechanism in the developing ...

Some birds come first -- a new approach to species conservation

2014-04-10

New Haven, Conn.— A Yale-led research team has developed a new approach to species conservation that prioritizes genetic and geographic rarity and applied it to all 9,993 known bird species.

"To date, conservation has emphasized the number of species, treating all species as equal," said Walter Jetz, the Yale evolutionary biologist who is lead author of a paper published April 10 in Current Biology. "But not all species are equal in their genetic or geographic rarity. We provide a framework for how such species information could be used for prioritizing conservation."

Worldwide, ...

Penn study finds mechanism that regulates lung function in disease Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome

2014-04-10

(PHILADELPHIA) – Researchers at Penn Medicine have discovered that the tumor suppressor gene folliculin (FLCN) is essential to normal lung function in patients with the rare disease Birt-Hogg-Dube (BHD) syndrome, a genetic disorder that affects the lungs, skin and kidneys. Folliculin's absence or mutated state has a cascading effect that leads to deteriorated lung integrity and an impairment of lung function, as reported in their findings in the current issue of Cell Reports.

"We discovered that without normal FLCN the alveolar epithelial cells (AEC) in these patients' ...

Ancient 'spider' images reveal eye-opening secrets

2014-04-10

VIDEO:

This is a video showing the 305-million-year-old harvestman fossil.

Click here for more information.

Stunning images of a 305-million-year-old harvestman fossil reveal ancestors of the modern-day arachnids had two sets of eyes rather than one.

The researchers say their findings, published in the journal Current Biology, add significant detail to the evolutionary story of this diverse and highly successful group of arthropods, which are found on every continent except Antarctica.

University ...

Poor mimics can succeed as long as they mimic the right trait

2014-04-10

There are both perfect and imperfect mimics in nature. An imperfect mimic might have a different body shape, size or colour pattern arrangement compared to the species it mimics.

Researchers have long been puzzled by the way poor mimicry can still be effective in fooling predators not to attack. In the journal Current Biology, researchers from Stockholm University now present a novel solution to the question of imperfect mimicry.

Mimicry is when animals have the appearance of another species in order to avoid being attacked. For instance, hoverflies have a similar ...

Enzyme 'wrench' could be key to stronger, more effective antibiotics

2014-04-10

Builders and factory workers know that getting a job done right requires precision and specialized tools. The same is true when you're building antibiotic compounds at the molecular level. New findings from North Carolina State University may turn an enzyme that acts as a specialized "wrench" in antibiotic assembly into a set of wrenches that will allow for greater customization. By modifying this enzyme, scientists hope to be able to design and synthesize stronger, more adaptable antibiotics from less expensive, natural compounds.

Kirromycin is a commonly known antibiotic ...

NEJM: High-risk seniors surgery decisions should be patient-centered, & physician led

2014-04-10

Surgery for frail, senior citizen patients can be risky. A new patient-centered, team-based approach to deciding whether these high-risk patients will benefit from surgery is championed in an April 10 Perspective of the New England Journal of Medicine. The Perspective suggests that the decision to have surgery must balance the advantages and disadvantages of surgical and non-surgical treatment as well as the patient's values and goals in a team-based setting that includes the patient, his or her family, the surgeon, the primary care physician and the physician anesthesiologist.

One ...

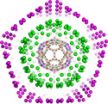

Virus structure inspires novel understanding of onion-like carbon nanoparticles

2014-04-10

Symmetry is ubiquitous in the natural world. It occurs in gemstones and snowflakes and even in biology, an area typically associated with complexity and diversity. There are striking examples: the shapes of virus particles, such as those causing the common cold, are highly symmetrical and look like tiny footballs.

A research programme led by Reidun Twarock at the University of York, UK has developed new mathematical tools to better understand the implications of this high degree of symmetry in these systems. The group pioneered a mathematical theory that reveals unprecedented ...

New towns going up in developing nations pose major risk to the poor

2014-04-10

DENVER (April 10, 2014) – Satellite city projects across the developing world are putting an increasing number of poor people at risk to natural hazards and climate change, according to a new study from the University of Colorado Denver.

Throughout Asia, Africa and Latin America `new towns' are rapidly being built on the outskirts of major cities with the goal of relieving population pressures, according to study author Andrew Rumbach, PhD, assistant professor of planning and design at CU Denver's College of Architecture and Planning.

The towns often sit in high flood ...