(Press-News.org) Johns Hopkins researchers report that they have identified a protein essential to the formation of the tiny brain region in mice that coordinates sleep-wake cycles and other so-called circadian rhythms.

By disabling the gene for that key protein in test animals, the scientists were able to home in on the mechanism by which that brain region, known as the suprachiasmatic nucleus or SCN, becomes the body's master clock while the embryo is developing.

The results of their experiments, reported online April 24 in Cell Reports, are an important step toward understanding how to better manage the disruptive effects experienced by shift workers, as well as treatment of people with sleep disorders, the researchers say.

"Shift workers tend to have higher rates of diabetes, obesity, depression and cancer. Many researchers think that's somehow connected to their irregular circadian rhythms, and thus to the SCN," says Seth Blackshaw, Ph.D., an associate professor in the Department of Neuroscience and the Institute for Cell Engineering at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "Our new research will help us and other researchers isolate the specific impacts of the SCN on mammalian health."

Blackshaw explains that every cell in the body has its own "clock" that regulates aspects such as its rate of energy use. The SCN is the master clock that synchronizes these individual timekeepers so that, for example, people feel sleepy at night and alert during the day, are hungry at mealtimes, and are prepared for the energy influx that hits fat cells after eating. "A unique property of the SCN is that if its cells are grown in a dish, they quickly synchronize their clocks with each another," Blackshaw says.

But while evidence like this gave researchers an idea of the SCN's importance, they hadn't completely teased its role apart from that of the body's other clocks, or from other parts of the brain.

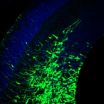

The Johns Hopkins team looked for ways to knock down SCN function by targeting and disabling certain genes that disrupt only the formation of the SCN clock. They analyzed which genes were active in different areas of developing mouse brains to identify those that were "turned on" only in the SCN. One of the "hits" was Lhx1, a member of a family of genes whose protein products affect development by controlling the activity of other genes. When the researchers turned off Lhx1 in the SCN of mouse embryos, the grown mice lacked distinctive biochemical signatures seen in the SCN of normal mice.

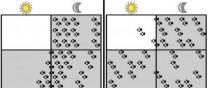

The genetically modified mice behaved differently, too. Some fell into a pattern of two to three separate cycles of sleep and activity per day, in contrast to the single daily cycle found in normal mice, while others' rhythms were completely disorganized, Blackshaw says. Though an SCN is present in mutant mice, it communicates poorly with clocks elsewhere in the body.

Blackshaw says he expects that the mutant mice will prove a useful tool in finding whether disrupted signaling from the SCN actually leads to the health problems that shift workers experience, and if so, how this might happen. Although mouse models do not correlate fully to human disease, their biochemical and genetic makeup is closely aligned.

Blackshaw's team also plans to continue studying the biochemical chain of events surrounding the Lhx1 protein to determine which proteins turn the Lhx1 gene on and which genes it, in turn, directly switches on or off. Those genes could be at the root of inherited sleep disorders, Blackshaw says, and the proteins they make could prove useful as starting points for the development of new drugs to treat insomnia and even jet lag.

INFORMATION:

Other authors on the paper were Joseph L. Bedont, Tara A. LeGates, Mardi S. Byerly, Hong Wang, Jianfei Hu, Alan C. Rupp, Jiang Qian, G. William Wong and Samer Hattar, all of Johns Hopkins, and Emily A. Slat and Erik D. Herzog of Washington University, Saint Louis.

This study was supported by the Johns Hopkins Brain Science Institute and the National Institute of Mental Health (grant number 63104).

Related stories:

Neural Protective Protein Has Two Faces

Weight Struggles? Blame New Neurons in Your Hypothalamus

Genetic 'Parts' List Now Available for Key Part of the Mammalian Brain

Researchers pinpoint protein crucial for development of biological rhythms in mice

2014-04-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Oldest pterodactyloid species discovered, named by international team of researchers

2014-04-24

WASHINGTON—An international research team, including a George Washington University (GW) professor, has discovered and named the earliest and most primitive pterodactyloid—a group of flying reptiles that would go on to become the largest known flying creatures to have ever existed—and established they flew above the earth some 163 million years ago, longer than previously known.

Working from a fossil discovered in northwest China, the project—led by University of South Florida (USF) paleontologist Brian Andres, James Clark of the GW Columbian College of Arts and Sciences ...

Fruit fly study identifies brain circuit that drives daily cycles of rest, activity

2014-04-24

PHILADELPHIA - Amita Sehgal, PhD, a professor of Neuroscience at the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, describes in Cell a circuit in the brain of fruit flies that controls their daily, rhythmic behavior of rest and activity. The new study also found that the fly version of the human brain protein known as corticotrophin releasing factor (CRF) is a major coordinating molecule in this circuit. Fly CRF, called DH44, is required for rest/activity cycles and is produced in cells that receive input from the clock cells in the fly brain. In mammals, CRF ...

Scientists find way to target cells resistant to chemo

2014-04-24

Scientists from The University of Manchester have identified a way to sensitise cancer cells to chemotherapy - making them more open to treatment.

The study published today in Cell Reports, could pave the way for the development of drugs to target cells that have become resistant to treatment.

The research team made the discovery whilst exploring the possible mechanisms behind resistance to chemotherapy drugs like Paclitaxel, often used to treat breast and colon cancer.

Dr Andrew Gilmore, who led the research team at The University of Manchester, is part of both the ...

New type of protein action found to regulate development

2014-04-24

Johns Hopkins researchers report they have figured out how the aptly named protein Botch blocks the signaling protein called Notch, which helps regulate development. In a report on the discovery, to appear online April 24 in the journal Cell Reports, the scientists say they expect the work to lead to a better understanding of how a single protein, Notch, directs actions needed for the healthy development of organs as diverse as brains and kidneys.

The Johns Hopkins team says their experiments show that Botch uses a never-before-seen mechanism, replacing one chemical group ...

Researchers discover new genetic brain disorder in humans

2014-04-24

A newly identified genetic disorder associated with degeneration of the central and peripheral nervous systems in humans, along with the genetic cause, is reported in the April 24, 2014 issue of Cell.

The findings were generated by two independent but collaborative scientific teams, one based primarily at Baylor College of Medicine and the Austrian Academy of Sciences, the other at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, the Academic Medical Center (AMC) in the Netherlands and the Yale University School of Medicine.

By performing DNA sequencing ...

Scientists reprogram blood cells into blood stem cells in mice

2014-04-24

BOSTON (April 24, 2014)—Researchers at Boston Children's Hospital have reprogrammed mature blood cells from mice into blood-forming hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), using a cocktail of eight genetic switches called transcription factors. The reprogrammed cells, which the researchers have dubbed induced HSCs (iHSCs), have the functional hallmarks of HSCs, are able to self-renew like HSCs, and can give rise to all of the cellular components of the blood like HSCs.

The findings mark a significant step toward one of the most sought-after goals of regenerative medicine: the ...

To mark territory or not to mark territory: Breaking the pheromone code

2014-04-24

LA JOLLA, CA— April 24, 2014 —A team led by scientists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) has deciphered the surprisingly versatile code by which chemical cues help trigger some of the most basic behaviors in mice.

The findings shed light on the evolution of mammalian behaviors—which include human behaviors—and their underlying brain mechanisms.

"How does an individual respond differently to the environment based on experience? How does it distinguish itself from others? These are some of the fundamental questions that a study like this one helps us address," ...

Genetic legacy from the Ottoman Empire: Single mutation causes rare brain disorder

2014-04-24

An international team of researchers have identified a previously unknown neurodegenerative disorder and discovered it is caused by a single mutation in one individual born during the Ottoman Empire in Turkey about 16 generations ago.

The genetic cause of the rare disorder was discovered during a massive analysis of the individual genomes of thousands of Turkish children suffering from neurological disorders.

"The more we learn about basic mechanisms behind rare forms of neuro-degeneration, the more novel insights we can gain into more common diseases such as Alzheimer's ...

Oops! Researchers find neural signature for mistake correction

2014-04-24

Culminating an 8 year search, scientists at the RIKEN-MIT Center for Neural Circuit Genetics captured an elusive brain signal underlying memory transfer and, in doing so, pinpointed the first neural circuit for "oops" ? the precise moment when one becomes consciously aware of a self-made mistake and takes corrective action.

The findings, published in Cell, verified a 20 year old hypothesis on how brain areas communicate. In recent years, researchers have been pursuing a class of ephemeral brain signals called gamma oscillations, millisecond scale bursts of synchronized ...

Large-scale identification and analysis of suppressive drug interactions

2014-04-24

TORONTO – Baker's yeast is giving scientists a better understanding of drug interactions, which are a major cause of hospitalization and illness world-wide.

When two or more medications are taken at the same time, one can suppress or enhance the effectiveness of the other. Similarly, one drug may magnify the toxicity of another. These types of interactions are a major cause of illness and hospitalization. However, there are severe practical limits on the practical scope of drug studies in humans. Limits come in part from ethics and in part from the staggering expense. ...