(Press-News.org) It's been about 10,000 years since our ancestors began farming, but crop domestication has taken much longer than expected – a delay caused less by genetics and more by culture and history, according to a new study co-authored by University of Guelph researchers.

The new paper digs at the roots not just of crop domestication but of civilization itself, says plant agriculture professor Lewis Lukens. "How did humans get food? Without domestication – without food – it's hard for populations to settle down," he said. "Domestication was the key for all subsequent human civilization."

The study appears this the current issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Lukens and Guelph PhD student Ann Meyer worked on the study with biologists at Oklahoma State University and Washington State University.

Examining crop domestication tells us how our ancestors developed food, feed and fibre leading to today's crops and products. Examining crop genetics might also help breeders and farmers looking to further refine and grow more crops for an expanding human population.

"This work is largely historical, but there are increasing demands for food production, and understanding the genetic basis of past plant improvement should help future efforts," he said.

The Guelph team analyzed data from earlier studies of domesticated cereal crop species, and the American scientists also performed field tests.

To study the historical effects of interactions between genes and between genes and the environment, they looked at genes controlling several crop plant traits.

Domestication has yielded modern crops whose seeds resist shattering, such as corn whose kernels stay on the cob instead of falling off. Early agriculturalists also shortened flowering time for crops, necessary in shorter growing seasons as in Canada.

Domestication traits are known to have developed more slowly than expected over the past 10,000 years. The researchers wondered whether genetic factors hindered transmission of genes controlling such traits. Instead, they found that domestication traits are often faithfully passed from parent to progeny, and often more so than ancestral traits, said Lukens.

That suggests cultural and historical factors – anything from war and famine to lack of communication among separated populations – accounted for the creeping rate of domestication.

"We conclude that the slow adaptation of domesticated plants by humans was likely due to historical factors that limited technological progress," said Lukens.

INFORMATION:

This research project stemmed from a meeting of anthropologists, archeobotanists and geneticists at the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center in North Carolina.

History to blame for slow crop taming: Study

2014-05-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Spotting a famous face in the crowd

2014-05-05

People can only recognize two faces in a crowd at a time – even if the faces belong to famous people. So says Volker Thoma of the University of East London in the UK in an article which sheds light on people's ability to process faces, published in Springer's journal Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. The findings have relevance to giving eye-witness testimony or for neuropsychological rehabilitation.

Thoma set up two experiments in which participants were asked to identify a famous politician such as Tony Blair and Bill Clinton or pop stars such as Mick Jagger and Robbie ...

Virtual patients, medical records and sleep queries may help reduce suicide

2014-05-05

AUGUSTA, Ga. - A virtual patient, the electronic medical record, and questions about how well patients sleep appear effective new tools in recognizing suicide risk, researchers say.

A fourth – and perhaps more powerful – tool against suicide is the comfort level of caregivers and family members in talking openly about it, said Dr. W. Vaughn McCall, Chairman of the Department of Psychiatry and Health Behavior at the Medical College of Georgia at Georgia Regents University.

Suicide is among the top 10 causes of death in the United States for every group age 10 and older, ...

Light-sensitive 'eyes' in plants

2014-05-05

Most plants try to turn towards the sun. Scientists from the University of Gothenburg have worked with Finnish colleagues to understand how light-sensitive proteins in plant cells change when they discover light. The results have been published in the most recent issue of Nature.

The family of proteins involved is known as the "phytochrome" family, and these proteins are found in all plant leaves. These proteins detect the presence of light and inform the cell whether it is day or night, or whether the plant is in the shade or the sun.

"You can think of them as the ...

Study reveals potentially unnecessary radiation after suspected sports-related injury

2014-05-05

VANCOUVER, BRITISH COLUMBIA – A new study of Utah youth with suspected sports-related head injuries found that emergency room visits for children with sports-related head injuries have increased since the state's concussion law passed in 2011, along with a rise in head CT scans -- leading to potentially unnecessary radiation exposure.

The results were announced at the Pediatric Academic Societies conference in Vancouver, British Columbia in May by William McDonnell, M.D., J.D., associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Utah.

The study, completed by McDonnell ...

New research explores how smoking while pregnant leads to other diseases

2014-05-05

VANCOUVER, BRITISH COLUMBIA – While many parents-to-be are aware that the health of their baby starts before they've actually arrived into the world, recent research reveals that "harm" (i.e., tobacco smoke, dirty air, poor nutrition, even preeclampsia) may not present itself disease-wise until well into adulthood or when a second harmful "hit" triggers the individual's susceptibility.

The results were announced at the Pediatric Academic Societies conference in Vancouver, British Columbia in May by Lisa Joss-Moore, Ph.D., University of Utah Department of Pediatrics. ...

Uncorking East Antarctica yields unstoppable sea-level rise

2014-05-05

The melting of a rather small ice volume on East Antarctica's shore could trigger a persistent ice discharge into the ocean, resulting in unstoppable sea-level rise for thousands of years to come. This is shown in a study now published in Nature Climate Change by scientists from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK). The findings are based on computer simulations of the Antarctic ice flow using improved data of the ground profile underneath the ice sheet.

"East Antarctica's Wilkes Basin is like a bottle on a slant," says lead-author Matthias Mengel, ...

Dual method to remove precancerous colon polyps may substantially reduce health-care costs

2014-05-05

Chicago, IL (May 5, 2014) — A surgical method combining two techniques for removing precancerous polyps during colonoscopies can substantially reduce the recovery time and the length of hospital stays, potentially saving the health-care system millions of dollars, according to research presented today at Digestive Disease Week® (DDW).

"Not only did we find that patients were discharged a day and a half earlier, we discovered other benefits, which could transform our approach to removing difficult colon polyps," said Jonathan Buscaglia, MD, the study's lead researcher ...

Women and PAD: Excellent treatment outcomes in spite of disease severity

2014-05-05

ANN ARBOR, Mich. – Women face greater limits on their lifestyle and have more severe symptoms as a result of peripheral artery disease (PAD), but minimally invasive procedures used to unclog arteries are just as successful as in men.

The success of procedures, such as angioplasty or stent placement, in treating women with leg PAD was revealed in a Journal of the American College of Cardiology study.

The study provides a rare look at gender differences in PAD. PAD happens when fatty deposits build up in arteries outside the heart, usually the arteries supplying fresh ...

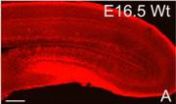

Cajal-Retzius cell loss and amyloidosis in Alzheimer's disease

2014-05-05

Cajal-Retzius cells are reelin-secreting neurons in the marginal zone of the neocortex and hippocampus. However, the relationship between Cajal-Retzius cells and Alzheimer's disease is unknown. Dr. Jinbo Deng and team from Henan University in China revealed that the number of Cajal-Retzius cells markedly reduced with age in both wild type and in mice over-expressing the Swedish double mutant form of amyloid precursor protein 695 (transgenic (Tg) 2576 mice). The decline in Cajal-Retzius cells in Tg2576 mice was found to occur concomitantly with the onset of Alzheimer's disease ...

New knowledge about muscular dystrophy

2014-05-05

The most common form of muscular dystrophy among adults is dystrophia myotonica type 1 (DM1), where approximately 1 in every 8000 is affected by the disease. The severity of the disease varies from mild forms to severe congenital forms. It is dominantly inherited and accumulates through generations, gaining increased severity and lowered age of onset. DM1 is characterised by accumulating toxic aggregates of ribonucleic acids (RNA) from a specific mutated gene (see figure 1).

When this RNA, which contains thousands of CUG nucleotide repeats, builds up in the cell, it attracts ...