(Press-News.org) VIDEO:

Wyss Institute Founding Director Don Ingber, Postdoctoral Fellow Yu-suke Torisawa, and Researcher Catherine Spina explain how and why they created bone marrow-on-a-chip, and how they got it to act like...

Click here for more information.

The latest organ-on-a-chip from Harvard's Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering reproduces the structure, functions and cellular make-up of bone marrow, a complex tissue that until now could only be studied intact in living animals, Institute researchers report in the May 4, 2014, online issue of Nature Methods. The device, dubbed "bone marrow-on-a-chip," gives scientists a much-needed new tool to test the effects of new drugs and toxic agents on whole bone marrow.

Specifically, the device could be used to develop safe and effective strategies to prevent or treat radiation's lethal effects on bone marrow without resorting to animal testing, a challenge being pursued at the Institute with funding from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In an initial test, the engineered bone marrow, like human marrow, withered in response to radiation unless a drug known to prevent radiation poisoning was present.

The bone marrow-on-a-chip could also be used in the future to maintain a cancer patient's own marrow temporarily while he or she underwent marrow-damaging treatments such as radiation therapy or high-dose chemotherapy.

"Bone marrow is an incredibly complex organ that is responsible for producing all of the blood cell types in our body, and our bone marrow chips are able to recapitulate this complexity in its entirety and maintain it in a functional form in vitro," said Don Ingber, M.D., Ph.D., Founding Director of the Wyss Institute, Judah Folkman Professor of Vascular Biology at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children's Hospital, Professor of Bioengineering at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and senior author of the paper.

Ingber leads a large effort to develop human organs-on-chips — small microfluidic devices that mimic the physiology of living organs. So far Wyss Institute teams have built lung, heart, kidney, and gut chips that reproduce key aspects of organ function, and they have more organs-on-chips in the works. The technology has been recognized internationally for its potential to replace animal testing of new drugs and environmental toxins, and as a new way for scientists to model human disease.

To build organ chips, in the past Wyss teams have combined multiple types of cells from an organ on a plastic microfluidic device, while steadily supplying nutrients, removing waste, and applying mechanical forces the tissues would face in the body. But bone marrow is so complex that they needed a new approach to mimic organ function.

This complexity arises because bone marrow has an integral relationship with bone. Marrow sits inside trabecular bone — a solid-looking type of bone with a porous, honeycombed interior. Throughout the honeycomb, conditions vary. Some areas are warmer, some cooler; some are oxygen-rich, others oxygen-starved, and the dozen or so cell types each have their own preferred spots. To add complexity, bone marrow cells communicate with each other by secreting and sensing a variety of biomolecules, which act locally to tell them whether to live, die, specialize or multiply.

Rather than trying to reproduce such a complex structure cell by cell, the researchers enlisted mice to do it.

"We figured, why not allow Mother Nature to help us build what she already knows how to build," said Catherine S. Spina, an M.D.-Ph.D. candidate at Boston University, researcher at the Wyss Institute, and co-lead author of the paper.

Specifically, Wyss Institute Postdoctoral Fellow Yu-suke Torisawa and Spina packed dried bone powder into an open, ring-shaped mold the size of a coin battery, and implanted the mold under the skin on the animal's back.

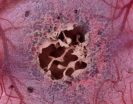

After eight weeks, they surgically removed the disk-shaped bone that had formed in the mold and examined it with a specialized CAT scanner. The scan showed a honeycomb-like structure that looked identical to natural trabecular bone.

The marrow looked like the real thing as well. When they stained the tissue and examined it under a microscope, the marrow was packed with blood cells, just like marrow from a living mouse. And when the researchers sorted the bone marrow cells by type and tallied their numbers, the mix of different types of blood and immune cells in the engineered bone marrow was identical to that in a mouse thighbone.

To sustain the engineered bone marrow outside of a living animal, the researchers surgically removed the engineered bone from mice, then placed it in a microfluidic device that mimics the circulation the tissue would experience in the body.

Marrow in the device remained healthy for up to one week. This is long enough, typically, to test the toxicity and effectiveness of a new drug.

The device also passed an initial test of its drug-testing capabilities. Like marrow from live mice, this engineered marrow was also susceptible to radiation — but an FDA-approved drug that protects irradiated patients also protected the marrow on the chip.

In the future, the researchers could potentially grow human bone marrow in immune-deficient mice. "This could be developed into an easy-to-use screening-based system that's personalized for individual patients," said coauthor James Collins, Ph.D., a Core Faculty member at the Wyss Institute and the William F. Warren Distinguished Professor at Boston University, where he leads the Center of Synthetic Biology.

Bone marrow-on-a-chip could also generate blood cells, which could circulate in an artificial circulatory system to supply a network of other organs-on-chips. The Defense Agency Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is funding efforts at the Wyss Institute to develop an interconnected network of ten organs-on-chips to study complex human physiology outside the body.

INFORMATION:

The work was funded by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, DARPA, and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University. In addition to Ingber, Torisawa, Spina and Collins, the authors included Tadanori Mammoto, Ph.D. and Akiko Mammoto, Ph.D., Instructors in Surgery at Boston Children's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, James Weaver, a Research Associate at the Wyss Institute, and Tracy Tat, a Research Technician at Boston Children's Hospital.

PRESS CONTACTS

Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University

Dan Ferber

dan.ferber@wyss.harvard.edu

+1 617-432-1547

Boston University College of Engineering

Michael Seele

mseele@bu.edu

+1 617-353-9766

Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences

Caroline Perry

cperry@seas.harvard.edu

+1 617-496-1351

IMAGES AND VIDEO AVAILABLE

About the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University

The Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University uses Nature's design principles to develop bioinspired materials and devices that will transform medicine and create a more sustainable world. Working as an alliance among Harvard's Schools of Medicine, Engineering, and Arts & Sciences, and in partnership with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston Children's Hospital, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, Boston University, Tufts University, and Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, the Institute crosses disciplinary and institutional barriers to engage in high-risk research that leads to transformative technological breakthroughs. By emulating Nature's principles for self-organizing and self-regulating, Wyss researchers are developing innovative new engineering solutions for healthcare, energy, architecture, robotics, and manufacturing. These technologies are translated into commercial products and therapies through collaborations with clinical investigators, corporate alliances, and new start-ups.

The Boston University College of Engineering offers a wide range of undergraduate, graduate and professional degrees in foundational and emerging engineering disciplines. Underlying the College's educational efforts is its commitment to creating Societal Engineers, who have an appreciation for how the engineer's unique skills can be used to improve our quality of life. Ranked among the nation's best engineering research institutions, the College's faculty attracts more than $50 million in external research support annually.

About the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences

The Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) serves as the connector and integrator of Harvard's teaching and research efforts in engineering, applied sciences, and technology. Through collaboration with researchers from all parts of Harvard, other universities, and corporate and foundational partners, we bring discovery and innovation directly to bear on improving human life and society. For more information, visit: http://seas.harvard.edu. END

Bone marrow-on-a-chip unveiled

Device captures complexity of living marrow in the laboratory; could help test new drugs to prevent lethal radiation exposure

2014-05-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A journey between XX and XY

2014-05-05

A team of researchers from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) has been involved in a thorough genetic investigation based on the case of a child suffering from the Nivelon-Nivelon-Mabille Syndrome, a complex condition characterised mainly by a sexual development disorder. Following a genome analysis of the patient and parents, the scientists, led by Serge Nef, Professor of the Department of Genetic Medicine and Development in the Faculty of Medicine, have identified not only the gene, but also the protein-producing mechanism, whose malfunctioning causes the syndrome in question. ...

Genetic approach helps design broadband metamaterial

2014-05-05

A specially formed material that can provide custom broadband absorption in the infrared can be identified and manufactured using "genetic algorithms," according to Penn State engineers, who say these metamaterials can shield objects from view by infrared sensors, protect instruments and be manufactured to cover a variety of wavelengths.

"The metamaterial has a high absorption over broad bandwidth," said Jeremy A. Bossard, postdoctoral fellow in electrical engineering. "Other screens have been developed for a narrow bandwidth, but this is the first that can cover a super-octave ...

Domestic violence victims more likely to take up smoking

2014-05-05

One third of women around the world have experienced physical or sexual violence at the hands of their intimate partners with consequences from post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression, to sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV. Now, in a new study in 29 low-income and middle-income countries, researchers at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health have identified yet another serious health risk associated with intimate partner violence (IPV): smoking.

The researchers examined the association between IPV and smoking among 231,892 women ...

Soy sauce molecule may unlock drug therapy for HIV patients

2014-05-05

COLUMBIA, Mo. – For HIV patients being treated with anti-AIDS medications, resistance to drug therapy regimens is commonplace. Often, patients develop resistance to first-line drug therapies, such as Tenofovir, and are forced to adopt more potent medications. Virologists at the University of Missouri now are testing the next generation of medications that stop HIV from spreading, and are using a molecule related to flavor enhancers found in soy sauce, to develop compounds that are more potent than Tenofovir.

"Patients who are treated for HIV infections with Tenofovir, ...

Terahertz imaging on the cheap

2014-05-05

Terahertz imaging, which is already familiar from airport security checkpoints, has a number of other promising applications — from explosives detection to collision avoidance in cars. Like sonar or radar, terahertz imaging produces an image by comparing measurements across an array of sensors. Those arrays have to be very dense, since the distance between sensors is proportional to wavelength.

In the latest issue of IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation, researchers in MIT's Research Laboratory for Electronics describe a new technique that could reduce the number ...

History to blame for slow crop taming: Study

2014-05-05

It's been about 10,000 years since our ancestors began farming, but crop domestication has taken much longer than expected – a delay caused less by genetics and more by culture and history, according to a new study co-authored by University of Guelph researchers.

The new paper digs at the roots not just of crop domestication but of civilization itself, says plant agriculture professor Lewis Lukens. "How did humans get food? Without domestication – without food – it's hard for populations to settle down," he said. "Domestication was the key for all subsequent human civilization."

The ...

Spotting a famous face in the crowd

2014-05-05

People can only recognize two faces in a crowd at a time – even if the faces belong to famous people. So says Volker Thoma of the University of East London in the UK in an article which sheds light on people's ability to process faces, published in Springer's journal Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. The findings have relevance to giving eye-witness testimony or for neuropsychological rehabilitation.

Thoma set up two experiments in which participants were asked to identify a famous politician such as Tony Blair and Bill Clinton or pop stars such as Mick Jagger and Robbie ...

Virtual patients, medical records and sleep queries may help reduce suicide

2014-05-05

AUGUSTA, Ga. - A virtual patient, the electronic medical record, and questions about how well patients sleep appear effective new tools in recognizing suicide risk, researchers say.

A fourth – and perhaps more powerful – tool against suicide is the comfort level of caregivers and family members in talking openly about it, said Dr. W. Vaughn McCall, Chairman of the Department of Psychiatry and Health Behavior at the Medical College of Georgia at Georgia Regents University.

Suicide is among the top 10 causes of death in the United States for every group age 10 and older, ...

Light-sensitive 'eyes' in plants

2014-05-05

Most plants try to turn towards the sun. Scientists from the University of Gothenburg have worked with Finnish colleagues to understand how light-sensitive proteins in plant cells change when they discover light. The results have been published in the most recent issue of Nature.

The family of proteins involved is known as the "phytochrome" family, and these proteins are found in all plant leaves. These proteins detect the presence of light and inform the cell whether it is day or night, or whether the plant is in the shade or the sun.

"You can think of them as the ...

Study reveals potentially unnecessary radiation after suspected sports-related injury

2014-05-05

VANCOUVER, BRITISH COLUMBIA – A new study of Utah youth with suspected sports-related head injuries found that emergency room visits for children with sports-related head injuries have increased since the state's concussion law passed in 2011, along with a rise in head CT scans -- leading to potentially unnecessary radiation exposure.

The results were announced at the Pediatric Academic Societies conference in Vancouver, British Columbia in May by William McDonnell, M.D., J.D., associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Utah.

The study, completed by McDonnell ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Nurses can deliver hospital care just as well as doctors

From surface to depth: 3D imaging traces vascular amyloid spread in the human brain

Breathing tube insertion before hospital admission for major trauma saves lives

Unseen planet or brown dwarf may have hidden 'rare' fading star

Study: Discontinuing antidepressants in pregnancy nearly doubles risk of mental health emergencies

Bipartisan members of congress relaunch Congressional Peripheral Artery Disease (PAD) Caucus with event that brings together lawmakers, medical experts, and patient advocates to address critical gap i

Antibody-drug conjugate achieves high response rates as frontline treatment in aggressive, rare blood cancer

Retina-inspired cascaded van der Waals heterostructures for photoelectric-ion neuromorphic computing

Seashells and coconut char: A coastal recipe for super-compost

Feeding biochar to cattle may help lock carbon in soil and cut agricultural emissions

Researchers identify best strategies to cut air pollution and improve fertilizer quality during composting

International research team solves mystery behind rare clotting after adenoviral vaccines or natural adenovirus infection

The most common causes of maternal death may surprise you

A new roadmap spotlights aging as key to advancing research in Parkinson’s disease

Research alert: Airborne toxins trigger a unique form of chronic sinus disease in veterans

University of Houston professor elected to National Academy of Engineering

UVM develops new framework to transform national flood prediction

Study pairs key air pollutants with home addresses to track progression of lost mobility through disability

Keeping your mind active throughout life associated with lower Alzheimer’s risk

TBI of any severity associated with greater chance of work disability

Seabird poop could have been used to fertilize Peru's Chincha Valley by at least 1250 CE, potentially facilitating the expansion of its pre-Inca society

Resilience profiles during adversity predict psychological outcomes

AI and brain control: A new system identifies animal behavior and instantly shuts down the neurons responsible

Suicide hotline calls increase with rising nighttime temperatures

What honey bee brain chemistry tells us about human learning

Common anti-seizure drug prevents Alzheimer’s plaques from forming

Twilight fish study reveals unique hybrid eye cells

Could light-powered computers reduce AI’s energy use?

Rebuilding trust in global climate mitigation scenarios

Skeleton ‘gatekeeper’ lining brain cells could guard against Alzheimer’s

[Press-News.org] Bone marrow-on-a-chip unveiledDevice captures complexity of living marrow in the laboratory; could help test new drugs to prevent lethal radiation exposure