(Press-News.org) Researchers at the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Medicine have discovered a protein molecule that seems to slow the progression of pulmonary fibrosis, a progressive lung disease that is often fatal three to five years after diagnosis.

The finding is reported in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.

Nearly five million people worldwide are affected by pulmonary fibrosis, which causes the lungs to become covered in fibrous scar tissue and leads to shortness of breath that gets more severe as the disease progresses.

Chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases can cause pulmonary fibrosis, as can exposure to asbestos, certain toxic gases, and even radiation therapy to treat lung cancer. Treatment options are limited because once scarring occurs, it is permanent. Lung transplantation remains the only effective treatment, but it is usually reserved for advanced cases.

"Finding a new therapeutic target for the treatment of pulmonary fibrosis is exciting, especially because the therapies available generally only slow the disease in very few patients," said Long Shuang Huang, UIC postdoctoral research associate in pharmacology and first author of the paper.

In previous genetic studies of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis -- where no cause can be identified -- the researchers found variations in several genes known to be involved in pulmonary fibrosis, including in the gene coding for a protein called lysocardiolipin acyltransferase, or LYCAT.

To investigate the potential role of LYCAT in pulmonary fibrosis, the researchers measured its levels in the blood of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients. Patients with the highest levels of LYCAT had significantly better lung function and higher three-year survival rates than those with lower levels.

"Since higher LYCAT levels directly correlate with better lung function and outcomes, we think the protein is playing some kind of protective role, or could be slowing the progress of pulmonary fibrosis," Huang said. "This suggests that boosting LYCAT levels in patients with pulmonary fibrosis may be a viable new therapeutic approach to treating the disease," Huang said.

The researchers also looked at the role of LYCAT in a mouse model of lung tissue scarring, and found that in mice where the LYCAT gene was knocked out, scar tissue developed more readily compared to mice with the gene. In mice engineered to produce elevated levels of LYCAT the development of scarring was much slower.

Looking for compounds or small molecules that increase the production of LYCAT is the next step for Huang and his colleagues.

INFORMATION:Co-authors on the paper are Viswanathan Natarajan, Biji Mathew, Peter Usatyuk, Dr. Evgeny Berdyshev, Dr. Wei Zhang, Yanmin Zhang, Sekhar Reddy, Dr. Anantha Harijith and Dr. Jalees Rehman of UIC; Haiquan Li, Tong Zhou, Dr. Yves Lussier and Dr. Joe Garcia of the University of Arizona; Yutong Zhao and Dr. Naftali Kaminski of the University of Pittsburgh; Shwu-Fan Ma and Dr. Imre Noth of the University of Chicago; and Dr. Sainath Kotha, Travis Gurney and Narasimham Parinandi of the Ohio State University.

The research was funded by National Institutes of Health grants P01-HL98050 and R01-GM094220, the Bernie Mac Foundation and the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation.

Protein molecule may improve survival in deadly lung disease

2014-05-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Two-lock box delivers cancer therapy

2014-05-06

Rice University scientists have designed a tunable virus that works like a safe deposit box. It takes two keys to open it and release its therapeutic cargo.

The Rice lab of bioengineer Junghae Suh has developed an adeno-associated virus (AAV) that unlocks only in the presence of two selected proteases, enzymes that cut up other proteins for disposal. Because certain proteases are elevated at tumor sites, the viruses can be designed to target and destroy the cancer cells.

The work appears online this week in the American Chemical Society journal ACS Nano.

AAVs are ...

Donor livers preserved and improved with room-temperature perfusion system

2014-05-06

A system developed by investigators at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Center for Engineering in Medicine (CEM) and the MGH Transplant Center has the potential to increase both the supply and the quality of donor organs for liver transplantation. In their report, which has been published online in the American Journal of Transplantation, the research team describes how use of a machine perfusion system delivering a supply of nutrients and oxygen though an organ's circulation at room temperature preserved and improved the metabolic function of donor livers in a ...

Study: Concussion rate in high-school athletes more than doubled in 7-year period

2014-05-06

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Concussion rates in U.S. high-school athletes more than doubled between 2005 and 2012, according to a new national study using data on nine team sports.

Overall, the rate increased from .23 to .51 concussions per 1,000 athlete exposures. An athlete exposure is defined as one athlete participating in one competition or practice.

The increase might appear to sound an alarm about sports safety, but the researchers suspect the upward trend in reported concussions reflects increased awareness – especially because the rates went up the most after the 2008-09 ...

Childhood obesity trends -- not time to celebrate, yet

2014-05-06

New Rochelle, NY, May 6, 2014—Despite reports in the media that the obesity rate among young children has declined dramatically during the past 10 years, that is not the conclusion reached by recent studies published in the medical literature. Those studies did, however, reveal some potentially encouraging findings, which are detailed in the Editorial "Childhood Obesity Trends: Time for Champagne?" published in Childhood Obesity, a peer-reviewed journal from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers. The article is available free on the Childhood Obesity website at http://www.liebertpub.com/chi.

"The ...

Ban cigarette filters to save the environment, suggest researchers

2014-05-06

Ban cigarette filters. Start a deposit-return scheme for used butts. Hold manufacturers responsible for clean-ups. Place warnings on packets about the impact of simply flicking one's used cigarettes away. These are among the policy measures that Thomas Novotny of the San Diego State University in the US and Elli Slaughter advocate to curb the environmental harm done through the large-scale littering of cigarette butts, packaging and matches. The suggestions are part of a review article in Springer's journal Current Environmental Health Reports.

Cigarette butts and other ...

Neutron star magnetic fields: Not so turbulent, after all?

2014-05-06

Neutron stars, the extraordinarily dense stellar bodies created when massive stars collapse, are known to host the strongest magnetic fields in the universe -- as much as a billion times more powerful than any man-made electromagnet. But some neutron stars are much more strongly magnetized than others, and this disparity has long puzzled astrophysicists.

Now, a study by McGill University physicists Konstantinos Gourgouliatos and Andrew Cumming sheds new light on the expected geometry of the magnetic field in neutron stars. The findings, published online April 29 in Physical ...

Detecting fetal chromosomal defects without risk

2014-05-06

Chromosomal abnormalities that result in birth defects and genetic disorders like Down syndrome remain a significant health burden in the United States and throughout the world, with some current prenatal screening procedures invasive and a potential risk to mother and unborn child.

In a paper published online this week in the Early Edition of PNAS, a team of scientists at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and in China describe a new benchtop semiconductor sequencing procedure and newly developed bioinformatics software tools that are fast, accurate, ...

Working to cure 'dry eye' disease

2014-05-06

WASHINGTON D.C. May 6, 2013 -- The eye is an exquisitely sensitive system with many aspects that remain somewhat of a mystery—both in the laboratory and in the clinic.

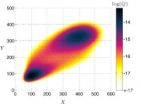

A U.S.-based team of mathematicians and optometrists is working to change this by gaining a better understanding of the inner workings of tear film distribution over the eye's surface. This, in turn, may lead to better treatments or a cure for the tear film disease known as "dry eye." They describe their work in the journal Physics of Fluids.

Dry eye disease afflicts millions of people worldwide, with ...

Predator-prey made simple

2014-05-06

WASHINGTON D.C. May 6, 2013 -- A team of U.K. researchers has developed a way to dramatically reduce the complexity of modeling "bistable" systems which involve the interaction of two evolving species where one changes faster than the other ("slow-fast systems"). Described in The Journal of Chemical Physics, the work paves the way for easier computational simulations and predictions involving such systems, which are found in fields as diverse as chemistry, biology and ecology.

Imagine, for instance, trying to predict how a population of whales would fare based on the ...

A cup of coffee a day may keep retinal damage away

2014-05-06

ITHACA, N.Y. – Coffee drinkers, rejoice! Aside from java's energy jolt, food scientists say you may reap another health benefit from a daily cup of joe: prevention of deteriorating eyesight and possible blindness from retinal degeneration due to glaucoma, aging and diabetes.

Raw coffee is, on average, just 1 percent caffeine, but it contains 7 to 9 percent chlorogenic acid, a strong antioxidant that prevents retinal degeneration in mice, according to a Cornell study published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry.

The retina is a thin tissue layer on the ...