(Press-News.org) Polar bears adapted to life in cold Arctic climates in part by relying on a high-fat diet mainly consisting of seals and their blubber. In a study published by Cell Press May 8th in the journal Cell, researchers discovered that mutations in genes involved in cardiovascular function allowed polar bears to rapidly evolve the ability to consume a fatty diet without developing high rates of heart disease. Moreover, the study revealed that polar bears diverged from brown bears less than 500,000 years ago—much more recently than estimates based on previous genomic data.

"In this limited amount of time, polar bears became uniquely adapted to the extremities of life out on the Arctic sea ice, enabling them to inhabit some of the world's harshest climates and most inhospitable conditions," says senior study author Rasmus Nielsen of the University of California, Berkeley.

Up to half of the body weight of polar bears consists of fat, and their blood cholesterol levels are high enough to cause cardiovascular disease in humans. But it has been a mystery how polar bears are able to cope with these major risk factors for heart disease. To understand the evolutionary processes driving such adaptations to extreme environments, it's essential to first establish a reliable time frame for when polar bears emerged as a species.

To address these questions, Nielsen teamed up with Eske Willerslev of the University of Copenhagen and Jun Wang of BGI-Shenzhen to sequence and analyze the complete genomes of 79 polar bears from Greenland and 10 brown bears from different locations around the globe. They found that the two species diverged less than 500,000 years ago, compared with estimates of up to five million years ago based on previously reported genomic data.

Since then, polar bears evolved rapidly by accumulating mutations in genes that are involved in cardiovascular function and fatty acid metabolism and have been linked to heart disease in humans. One such gene, called APOB, is known to play a role in moving cholesterol from the bloodstream into cells, thus reducing the risk of heart disease. "Such a drastic genetic response to chronically elevated levels of fat and cholesterol in the diet has not previously been reported," Willerslev says. "It certainly encourages a move beyond the standard model organisms in our search for the underlying genetic causes of human cardiovascular diseases."

INFORMATION:

Cell, Liu et al.: "Population Genomics Reveal Recent Speciation And Rapid Evolutionary Adaptation In Polar Bears."

Polar bear genome reveals rapid adaptation to fatty diet

2014-05-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Using genetics to measure the environmental impact of salmon farming

2014-05-08

Determining species diversity makes it possible to estimate the impact of human activity on marine ecosystems accurately. The environmental effects of salmon farming have been assessed, until now, by visually identifying the animals living in the marine sediment samples collected at specific distances from farming sites. A team led by Jan Pawlowski, professor at the Faculty of Science of the University of Geneva (UNIGE), Switzerland, analysed this type of sediment using a technique known as "DNA barcoding" that targets certain micro-organisms. Their research, which has ...

Humans may benefit from new insights into polar bear's adaptation to high-fat diet

2014-05-08

A comparison of the genomes of polar bears and brown bears reveals that the polar bear is a much younger species than previously believed, having diverged from brown bears less than 500,000 years ago.

The analysis also uncovered several genes that may be involved in the polar bears' extreme adaptations to life in the high Arctic. The species lives much of its life on sea ice, where it subsists on a blubber-rich diet of primarily marine mammals.

The genes pinpointed by the study are related to fatty acid metabolism and cardiovascular function, and may explain the bear's ...

Better cognition seen with gene variant carried by 1 in 5

2014-05-08

A scientific team led by the Gladstone Institutes and UC San Francisco has discovered that a common form of a gene already associated with long life also improves learning and memory, a finding that could have implications for treating age-related diseases like Alzheimer's.

The researchers found that people who carry a single copy of the KL-VS variant of the KLOTHO gene perform better on a wide variety of cognitive tests. When the researchers modeled the effects in mice, they found it strengthened the connections between neurons that make learning possible – what is known ...

Penn yeast study identifies novel longevity pathway

2014-05-08

PHILADELPHIA - Ancient philosophers looked to alchemy for clues to life everlasting. Today, researchers look to their yeast. These single-celled microbes have long served as model systems for the puzzle that is the aging process, and in this week's issue of Cell Metabolism, they fill in yet another piece.

The study, led by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, identifies a new molecular circuit that controls longevity in yeast and more complex organisms and suggests a therapeutic intervention that could mimic the lifespan-enhancing effect of caloric restriction, ...

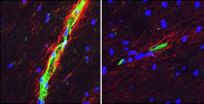

Study helps explain why MS is more common in women

2014-05-08

A newly identified difference between the brains of women and men with multiple sclerosis (MS) may help explain why so many more women than men get the disease, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis report.

In recent years, the diagnosis of MS has increased more rapidly among women, who get the disorder nearly four times more than men. The reasons are unclear, but the new study is the first to associate a sex difference in the brain with MS.

The findings appear May 8 in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Studying mice and people, ...

Immune cells found to fuel colon cancer stem cells

2014-05-08

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — A subset of immune cells directly target colon cancers, rather than the immune system, giving the cells the aggressive properties of cancer stem cells.

So finds a new study that is an international collaboration among researchers from the United States, China and Poland.

"If you want to control cancer stem cells through new therapies, then you need to understand what controls the cancer stem cells," says senior study author Weiping Zou, M.D., Ph.D., Charles B. de Nancrede Professor of surgery, immunology and biology at the University of Michigan Medical ...

What doesn't kill you may make you live longer

2014-05-08

What is the secret to aging more slowly and living longer? Not antioxidants, apparently.

Many people believe that free radicals, the sometimes-toxic molecules produced by our bodies as we process oxygen, are the culprit behind aging. Yet a number of studies in recent years have produced evidence that the opposite may be true.

Now, researchers at McGill University have taken this finding a step further by showing how free radicals promote longevity in an experimental model organism, the roundworm C. elegans. Surprisingly, the team discovered that free radicals – also ...

Population genomics study provides insights into how polar bears adapt to the Arctic

2014-05-08

May 8, 2014, Shenzhen, China – In a paper published in the May 8 issue of the journal Cell as the cover story, researches from BGI, University of California, University of Copenhagen and other institutes presented the first polar bear genome and their new findings about how polar bear successfully adapted to life in the high Arctic environment, and its demographic history throughout the history of its adaptation.

Polar bears are at the top of the food chain, and spend most of their lifetimes on the sea ice largely within the Arctic Circle. They were well known to the ...

How immune cells use steroids

2014-05-08

Hinxton, 8 May 2014 – Researchers at the European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI) and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute have discovered that some immune cells turn themselves off by producing a steroid. The findings, published in Cell Reports, have implications for the study of cancers, autoimmune diseases and parasitic infections.

If you've ever used a steroid, for example cortisone cream on eczema, you'll have seen first-hand how efficient steroids are at suppressing the immune response. Normally, when your body senses that immune cells have finished their job, ...

Just keep your promises: Going above and beyond does not pay off

2014-05-08

May 8, 2014 - If you are sending Mother's Day flowers to your mom this weekend, chances are you opted for guaranteed delivery: the promise that they will arrive by a certain time. Should the flowers not arrive in time, you will likely feel betrayed by the sender for breaking their promise. But if they arrive earlier, you likely will be no happier than if they arrive on time, according to new research. The new work suggests that we place such a high premium on keeping a promise that exceeding it confers little or no additional benefit.

Whether we make them with a person ...