(Press-News.org) A comparison of the genomes of polar bears and brown bears reveals that the polar bear is a much younger species than previously believed, having diverged from brown bears less than 500,000 years ago.

The analysis also uncovered several genes that may be involved in the polar bears' extreme adaptations to life in the high Arctic. The species lives much of its life on sea ice, where it subsists on a blubber-rich diet of primarily marine mammals.

The genes pinpointed by the study are related to fatty acid metabolism and cardiovascular function, and may explain the bear's ability to cope with a high-fat diet while avoiding fatty plaques in their arteries and the cardiovascular diseases that afflict humans with diets rich in fat. These genes may provide insight into how to protect humans from the ill effects of a high-fat diet.

The study was a collaboration between Danish researchers, led by Eske Willerslev and including Rune Dietz, Christian Sonne and Erik W. Born, who provided polar bear blood and tissue samples; and researchers at BGI in China, including Shiping Liu, Guojie Zhang and Jun Wang, who sequenced the genomes and analyzed the data together with a team of UC Berkeley researchers, including Eline Lorenzen, Matteo Fumagalli and Rasmus Nielsen. Nielsen is a UC Berkeley professor of integrative biology and of statistics.

"For polar bears, profound obesity is a benign state," said Lorenzen, one of the lead authors and a UC Berkeley postdoctoral fellow. "We wanted to understand how they are able to cope with that."

"The promise of comparative genomics is that we learn how other organisms deal with conditions that we also are exposed to," said Nielsen, a member of UC Berkeley's Center for Theoretical Evolutionary Genomics. "For example, polar bears have adapted genetically to a high fat diet that many people now impose on themselves. If we learn a bit about the genes that allows them to deal with that, perhaps that will give us tools to modulate human physiology down the line."

The findings accompany the publication of the first assembled genome of the polar bear as the cover story in the May 8 issue of the journal Cell.

Close cousins

The genome analysis comes at a time when the polar bear population worldwide, estimated at between 20,000 and 25,000, is declining and its habitat, Arctic sea ice, is rapidly disappearing. As the northern latitudes warm, the polar bear's distant cousin, the brown or grizzly bear (Ursus arctos), is moving farther north and occasionally interbreeding with the polar bear (Ursus maritimus) to produce hybrids dubbed pizzlies.

Their ability to interbreed is a result of this very close relationship, Nielsen said, which is one-tenth the evolutionary distance between chimpanzees and humans. Previous estimates of the divergence time between polar bears and brown bears ranged from 600,000 to 5 million years ago.

"It's really surprising that the divergence time is so short. All the unique adaptations polar bears have to the arctic environment must have evolved in a very short amount of time," he said. These adaptations include not only a change from brown to white fur and development of a sleeker body, but big physiological and metabolic changes as well. "There has been a lot of debate about it, but I think we really nailed down what the divergence time is between them, and it is surprisingly recent."

Genetic changes affect fat metabolism

The genome comparison reveals that over several hundred thousand years, natural selection drove major changes in genes related to fat transport in the blood and fatty acid metabolism. One of the most strongly selected genes is APOB, which in mammals encodes the main protein in LDL (low density lipoprotein), known widely as "bad" cholesterol. Changes or mutations in this gene reflect the critical nature of fat in the polar bear diet and the animal's need to deal with high blood levels of glucose and triglycerides, in particular cholesterol, which would be dangerous in humans. Fat comprises up to half the weight of a polar bear.

"The life of a polar bear revolves around fat," Lorenzen said. "Nursing cubs rely on milk that can be up to 30 percent fat and adults eat primarily blubber of marine mammal prey. Polar bears have large fat deposits under their skin and, because they essentially live in a polar desert and don't have access to fresh water for most of the year, rely on metabolic water, which is a byproduct of the breakdown of fat."

She noted that the evolution of a new metabolism to deal with high dietary fat must have happened very quickly, in just a few hundred thousand years, because we know that polar bears already subsisted on a marine diet 100,000 years ago.

What drove the evolution of polar bears is unclear, though the split from brown bears (dated at 343,000–479,000 years ago) coincides with a particularly warm 50,000-year interglacial period known as Marine Isotope Stage 11. Environmental shifts following climate changes could have encouraged brown bears to extend their range much farther north. When the warm interlude ended and a glacial cold period set in, a pocket of brown bears may have become isolated and forced to adapt rapidly to new conditions.

Samples from all over Arctic

The analysis included blood and tissue samples from 79 Greenlandic polar bears and 10 brown bears from Sweden, Finland, Glacier National Park in Alaska and the Admiralty, Baranof, and Chichagof (ABC) Islands off the Alaskan coast.

According to Lorenzen, the "key that allowed us to unlock the door of polar bear evolution" was a method devised by UC Berkeley mathematics graduate student Kelley Harris that has been used to estimate human demographic history. The approach, referred to as the identity by state (IBS) tract method, has proved powerful in estimating when ancient human populations diverged, their past population sizes and when and how much they interbred.

INFORMATION:

The work at UC Berkeley was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (2R14003229-07).

Humans may benefit from new insights into polar bear's adaptation to high-fat diet

Genome comparison gives clues to how polar bears rapidly evolved to cope with lipid-rich diet

2014-05-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Better cognition seen with gene variant carried by 1 in 5

2014-05-08

A scientific team led by the Gladstone Institutes and UC San Francisco has discovered that a common form of a gene already associated with long life also improves learning and memory, a finding that could have implications for treating age-related diseases like Alzheimer's.

The researchers found that people who carry a single copy of the KL-VS variant of the KLOTHO gene perform better on a wide variety of cognitive tests. When the researchers modeled the effects in mice, they found it strengthened the connections between neurons that make learning possible – what is known ...

Penn yeast study identifies novel longevity pathway

2014-05-08

PHILADELPHIA - Ancient philosophers looked to alchemy for clues to life everlasting. Today, researchers look to their yeast. These single-celled microbes have long served as model systems for the puzzle that is the aging process, and in this week's issue of Cell Metabolism, they fill in yet another piece.

The study, led by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, identifies a new molecular circuit that controls longevity in yeast and more complex organisms and suggests a therapeutic intervention that could mimic the lifespan-enhancing effect of caloric restriction, ...

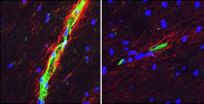

Study helps explain why MS is more common in women

2014-05-08

A newly identified difference between the brains of women and men with multiple sclerosis (MS) may help explain why so many more women than men get the disease, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis report.

In recent years, the diagnosis of MS has increased more rapidly among women, who get the disorder nearly four times more than men. The reasons are unclear, but the new study is the first to associate a sex difference in the brain with MS.

The findings appear May 8 in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Studying mice and people, ...

Immune cells found to fuel colon cancer stem cells

2014-05-08

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — A subset of immune cells directly target colon cancers, rather than the immune system, giving the cells the aggressive properties of cancer stem cells.

So finds a new study that is an international collaboration among researchers from the United States, China and Poland.

"If you want to control cancer stem cells through new therapies, then you need to understand what controls the cancer stem cells," says senior study author Weiping Zou, M.D., Ph.D., Charles B. de Nancrede Professor of surgery, immunology and biology at the University of Michigan Medical ...

What doesn't kill you may make you live longer

2014-05-08

What is the secret to aging more slowly and living longer? Not antioxidants, apparently.

Many people believe that free radicals, the sometimes-toxic molecules produced by our bodies as we process oxygen, are the culprit behind aging. Yet a number of studies in recent years have produced evidence that the opposite may be true.

Now, researchers at McGill University have taken this finding a step further by showing how free radicals promote longevity in an experimental model organism, the roundworm C. elegans. Surprisingly, the team discovered that free radicals – also ...

Population genomics study provides insights into how polar bears adapt to the Arctic

2014-05-08

May 8, 2014, Shenzhen, China – In a paper published in the May 8 issue of the journal Cell as the cover story, researches from BGI, University of California, University of Copenhagen and other institutes presented the first polar bear genome and their new findings about how polar bear successfully adapted to life in the high Arctic environment, and its demographic history throughout the history of its adaptation.

Polar bears are at the top of the food chain, and spend most of their lifetimes on the sea ice largely within the Arctic Circle. They were well known to the ...

How immune cells use steroids

2014-05-08

Hinxton, 8 May 2014 – Researchers at the European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI) and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute have discovered that some immune cells turn themselves off by producing a steroid. The findings, published in Cell Reports, have implications for the study of cancers, autoimmune diseases and parasitic infections.

If you've ever used a steroid, for example cortisone cream on eczema, you'll have seen first-hand how efficient steroids are at suppressing the immune response. Normally, when your body senses that immune cells have finished their job, ...

Just keep your promises: Going above and beyond does not pay off

2014-05-08

May 8, 2014 - If you are sending Mother's Day flowers to your mom this weekend, chances are you opted for guaranteed delivery: the promise that they will arrive by a certain time. Should the flowers not arrive in time, you will likely feel betrayed by the sender for breaking their promise. But if they arrive earlier, you likely will be no happier than if they arrive on time, according to new research. The new work suggests that we place such a high premium on keeping a promise that exceeding it confers little or no additional benefit.

Whether we make them with a person ...

Universal neuromuscular training an inexpensive, effective way to reduce

2014-05-08

ROSEMENT, Ill.─As participation in high-demand sports such as basketball and soccer has increased over the past decade, so has the number of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries in teens and young adults. In a study appearing today in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (JBJS) (a research summary was presented at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons in March), researchers found that universal neuromuscular training for high school and college-age athletes—which focuses on the optimal way to bend, jump, land and pivot the knee—is ...

Collaboration between psychologists and physicians important to improving primary health care

2014-05-08

WASHINGTON - Primary care teams that include both psychologists and physicians would help address known barriers to improved primary health care, including missed diagnoses, a lack of attention to behavioral factors and limited patient access to needed care, according to health care experts writing in a special issue of American Psychologist, the flagship journal of the American Psychological Association.

"At the heart of the new primary care team is a partnership between a primary care clinician and a psychologist or other mental health professional. The team works together ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Brain stimulation can nudge people to behave less selfishly

Shorter treatment regimens are safe options for preventing active tuberculosis

How food shortages reprogram the immune system’s response to infection

The wild physics that keeps your body’s electrical system flowing smoothly

From lab bench to bedside – research in mice leads to answers for undiagnosed human neurodevelopmental conditions

More banks mean higher costs for borrowers

Mohebbi, Manic, & Aslani receive funding for study of scalable AI-driven cybersecurity for small & medium critical manufacturing

Media coverage of Asian American Olympians functioned as 'loyalty test'

University of South Alabama Research named Top 10 Scientific Breakthroughs of 2025

Genotype-specific response to 144-week entecavir therapy for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B with a particular focus on histological improvement

‘Stiff’ cells provide new explanation for differing symptoms in sickle cell patients

New record of Great White Shark in Spain sparks a 160-year review

Prevalence of youth overweight, obesity, and severe obesity

GLP-1 receptor agonists plus progestins and endometrial cancer risk in nonmalignant uterine diseases

Rejuvenating neurons restores learning and memory in mice

Endocrine Society announces inaugural Rare Endocrine Disease Fellows Program

Sensorimotor integration by targeted priming in muscles with electromyography-driven electro-vibro-feedback in robot-assisted wrist/hand rehabilitation after stroke

New dual-action compound reduces pancreatic cancer cell growth

Wastewater reveals increase in new synthetic opioids during major New Orleans events

Do cash transfers lead to traumatic injury or death?

Eva Vailionis, MS, CGC is presented the 2026 ACMG Foundation Genetic Counselor Best Abstract Award by The ACMG Foundation

Where did that raindrop come from? Tracing the movement of water molecules using isotopes

Planting tree belts on wet farmland comes with an overlooked trade-off

Continuous lower limb biomechanics prediction via prior-informed lightweight marker-GMformer

Researchers discover genetic link to Barrett’s esophagus offering new hope for esophageal cancer patients

Endocrine Society announces inaugural Rare Endocrine Disease Fellows Series

New AI model improves accuracy of food contamination detection

Egalitarianism among hunter-gatherers

AI-Powered R&D Acceleration: Insilico Medicine and CMS announce multiple collaborations in central nervous system and autoimmune diseases

AI-generated arguments are persuasive, even when labeled

[Press-News.org] Humans may benefit from new insights into polar bear's adaptation to high-fat dietGenome comparison gives clues to how polar bears rapidly evolved to cope with lipid-rich diet