(Press-News.org) Almost every biological process involves sensing the presence of a certain chemical. Finely tuned over millions of years of evolution, the body's different receptors are shaped to accept certain target chemicals. When they bind, the receptors tell their host cells to produce nerve impulses, regulate metabolism, defend the body against invaders or myriad other actions depending on the cell, receptor and chemical type.

Now, researchers from the University of Pennsylvania have led an effort to create an artificial chemical sensor based on one of the human body's most important receptors, one that is critical in the action of painkillers and anesthetics. In these devices, the receptors' activation produces an electrical response rather than a biochemical one, allowing that response to be read out by a computer.

By attaching a modified version of this mu-opioid receptor to strips of graphene, they have shown a way to mass produce devices that could be useful in drug development and a variety of diagnostic tests. And because the mu-opioid receptor belongs to the most common class of such chemical sensors, the findings suggest that the same technique could be applied to detect a wide range of biologically relevant chemicals.

The study, published in the journal Nano Letters, was led by A.T. Charlie Johnson, director of Penn's Nano/Bio Interface Center and professor of physics in Penn's School of Arts & Sciences; Renyu Liu, assistant professor of anesthesiology in Penn's Perelman School of Medicine; and Mitchell Lerner, then a graduate student in Johnson's lab. It was made possible through a collaboration with Jeffery Saven, professor of chemistry in Penn Arts & Sciences. The Penn team also worked with researchers from the Seoul National University in South Korea.

Their study combines recent advances from several disciplines.

Johnson's group has extensive experience attaching biological components to nanomaterials for use in chemical detectors. Previous studies have involved wrapping carbon nanotubes with single-stranded DNA to detect odors related to cancer and attaching antibodies to nanotubes to detect the presence of the bacteria associated with Lyme disease.

The groups of Saven and Liu have used computational techniques to redesign the mu-opioid receptor to make it easier to use in research. In its natural state, the receptor is not water soluble, making many common experimental techniques impossible. Worse, proteins like this receptor would normally be grown in genetically engineered bacteria to generate the quantity necessary for extensive study, but parts of the natural mu-opioid receptor are toxic to the E. coli used in this method.

After Saven and Liu addressed these problems with the redesigned receptor, they saw that it might be useful to Johnson, who had previously published a study on attaching a similar receptor protein to carbon nanotubes. In that case, the protein was difficult to grow genetically, and Johnson and his colleagues also needed to include additional biological structures from the receptors' natural membranes in order to keep them stable.

In contrast, the computationally redesigned protein could be readily grown and attached directly to graphene, opening up the possibility of mass producing biosensor devices that utilize these receptors.

"Due to the challenges associated with isolating these receptors from their membrane environment without losing functionality," Liu said, "the traditional methods of studying them involved indirectly investigating the interactions between opioid and the receptor via radioactive or fluorescent labeled ligands, for example. This multi-disciplinary effort overcame those difficulties, enabling us to investigate these interactions directly in a cell free system without the need to label any ligands."

"This is the kind of project that the Penn campus makes possible," Saven said. "Even with the medical school across the street and the physics department nearby, I don't think we'd be as close collaborators without the Nano/Bio Interface Center supporting us."

With Saven and Liu providing a version of the receptor that could stably bind to sheets of graphene, Johnson's team refined their process of manufacturing those sheets and connecting them to the circuitry necessary to make functional devices.

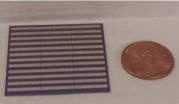

"We start by growing a piece of graphene that is about six inches wide by 12 inches long," Johnson said. "That's a pretty big piece of graphene, but we don't work with the whole thing at once. Mitchell Lerner, the lead author of the study, came up with a very clever idea to cut down on chemical contamination. We start with a piece that is about an inch square, then separate them into ribbons that are about 50 microns across.

"The nice thing about these ribbons is that we can put them right on top of the rest of the circuitry, and then go on to attach the receptors. This really reduces the potential for contamination, which is important because contamination greatly degrades the electrical properties we measure."

Because the mechanism by which the device reports on the presence of the target molecule relies only on the receptor's proximity to the nanostructure when it binds to the target, Johnson's team could employ the same chemical technique for attaching the antibodies and other receptors used in earlier studies.

Once attached to the ribbons, the opioid receptors would produce changes in the surrounding graphene's electrical properties whenever they bound to their target. Those changes would then produce electrical signals that would be transmitted to a computer via neighboring electrodes.

The high reliability of the manufacturing process — only one of the 193 devices on the chip failed — enables applications in both clinical diagnostics and further research.

"We can measure each device individually and average the results, which greatly reduces the noise," said Johnson. "Or you could imagine attaching 10 different kinds of receptors to 20 devices each, all on the same chip, if you wanted to test for multiple chemicals at once."

In the researchers' experiment, they tested their devices' ability to detect the concentration of a single type of molecule. They used naltrexone, a drug used in alcohol and opioid addiction treatment, because it binds to and blocks the natural opioid receptors that produce the narcotic effects patients seek.

"It's not clear whether the receptors on the devices are as selective as they are in the biological context," Saven said, "as the ones on your cells can tell the difference between an agonist, like morphine, and an antagonist, like naltrexone, which binds to the receptor but does nothing. By working with the receptor-functionalized graphene devices, however, not only can we make better diagnostic tools, but we can also potentially get a better understanding of how the bimolecular system actually works in the body."

"Many novel opioids have been developed over the centuries," Liu said. "However, none of them has achieved potent analgesic effects without notorious side effects, including devastating addiction and respiratory depression. This novel tool could potentially aid the development of new opioids that minimize these side effects."

Wherever these devices find applications, they are a testament to the potential usefulness of the Nobel-prize winning material they are based on.

"Graphene gives us an advantage," Johnson said, "in that its uniformity allows us to make 192 devices on a one-inch chip, all at the same time. There are still a number of things we need to work out, but this is definitely a pathway to making these devices in large quantities."

INFORMATION:

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health, Foundation for Anesthesia Education and Research, Mary Elizabeth Groff Foundation and Department of Anesthesiology at the Perelman School of Medicine.

Also contributing to the study were Gang Hee Han, Sung Ju Hong and Alexander Crook of Penn Arts & Sciences' Department of Physics and Astronomy; Felipe Matsunaga and Jin Xi of the Department of Anesthesiology at the Perelman School of Medicine, José Manuel Pérez-Aguilar of Penn Arts & Sciences' Department of Chemistry; and Yung Woo Park of Seoul National University. Mitchell Lerner is now at SPAWAR Systems Center Pacific, Felipe Matsunaga at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, José Manuel Pérez-Aguilar at Cornell University and Sung Ju Hong at Seoul National University.

Penn research combines graphene and painkiller receptor into scalable chemical sensor

2014-05-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Having a sense of purpose may add years to your life

2014-05-12

Feeling that you have a sense of purpose in life may help you live longer, no matter what your age, according to research published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

The research has clear implications for promoting positive aging and adult development, says lead researcher Patrick Hill of Carleton University in Canada:

"Our findings point to the fact that finding a direction for life, and setting overarching goals for what you want to achieve can help you actually live longer, regardless of when you find your purpose," ...

PSC, Hopkins computer model helps Benin vaccinate more kids at lower cost

2014-05-12

The HERMES Logistics Modeling Team, consisting of researchers from Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center (PSC), the University of Pittsburgh School of Engineering and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, have used HERMES, their modeling software, to help the Republic of Benin in West Africa determine how to bring more lifesaving vaccines to its children. The team reports its findings this month in the journal Vaccine.

Results from the HERMES model have helped the country enact some initial changes in their vaccine delivery system, which may lead to further ...

A form of immune therapy might be effective for multiple myeloma

2014-05-12

COLUMBUS, Ohio – A new study by researchers at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute (OSUCCC – James) provides evidence that genetically modifying immune cells might effectively treat multiple myeloma, a disease that remains incurable and will account for an estimated 24,000 new cases and 11,100 deaths in 2014

The researchers modified a type of human immune cell – called T lymphocytes, or T cells – to target a molecule called CS1, which is found on more than 95 percent of myeloma ...

Respect for human rights is improving

2014-05-12

By ignoring how the collection of data on political repression changes over time, human rights watchers may be misjudging reports that seem to show respect for human rights has not been improving, according to a Penn State political scientist.

Many political scientists and sociologists believe that allegations of human rights abuses drawn from sources such as the U.S. State Department and Amnesty International over the past few decades show that attention to human rights is stagnating, said Christopher Fariss, assistant professor of political science. However, a new ...

Scientists discover a natural molecule to treat type 2 diabetes

2014-05-12

Quebec City, May 12, 2014 – Researchers at the Université Laval Faculty of Medicine, the Quebec Heart and Lung Institute Research Center, and the Institute of Nutrition and Functional Foods have discovered a natural molecule that could be used to treat insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. The molecule, a derivative of omega-3 fatty acids, mimics some of the effects of physical exercise on blood glucose regulation. The details of the discovery made by Professor André Marette and his team are published today in Nature Medicine.

It has been known for some time that omega-3 ...

The largest electrical networks are not the best

2014-05-12

This news release is available in Spanish. There is an optimum size for electrical networks if what is being considered is the risk of a blackout. This is the conclusion reached by a scientific study done by researchers at Universidad Carlos III in Madrid; the study analyzes the dynamics of these complex infrastructures.

In 1928, the British biologist and geneticist John Haldane wrote the essay "On being the right size" in which he stated that "For every type of animal there is a most convenient size, and a large change in size inevitably carries with it a change of ...

Entering adulthood in a recession linked to lower narcissism later in life

2014-05-12

We often attribute the narcissistic tendencies of others to parenting practices or early social experiences. But new research reveals that economic conditions in the formative years of early adulthood may also play a role.

The research shows that people who entered their adulthood during hard economic times are less narcissistic later in life than those who came of age during more prosperous times.

"These findings suggest that economic conditions during this formative period of life not only affect how people think about finances and politics, but also how they think ...

Round 2: Reactions serves up a second helping of chemistry life hacks (video)

2014-05-12

WASHINGTON, May 12, 2014 — It was the video that started it all, and now the latest installment of the segment that is one-part Mendeleev, one-part MacGyver is here. The American Chemical Society's (ACS') Reactions video team is proud to debut round two of chemistry life hacks. This volume is packed full of new chemistry-fueled solutions for everyday problems, like spotting rotten eggs, reviving soggy green vegetables and fixing busted buttons. The video is available at http://youtu.be/ReGfd_s9gXA

INFORMATION:

Subscribe to the series at Reactions YouTube, and follow ...

Triple negative breast cancer, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status

2014-05-12

ATLANTA – May 12, 2014—An analysis of a large nationwide dataset finds that regardless of their socioeconomic status, black women were nearly twice as likely as white women to be diagnosed with triple-negative (TN) breast cancer, a subtype that has a poorer prognosis. The analysis also found that Asian/Pacific Islander women were more likely to be diagnosed with another subtype of breast cancer: so-called human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–overexpressing breast cancer. The study appears early online in Breast Cancer Research and Treatment.

Triple-negative ...

Hospitals recover from recession, some financial issues remain

2014-05-12

The recent economic recession affected hospitals across the nation, regardless of financial status, but following the rebound, financially weak and safety-net hospitals continue to struggle, according to health researchers.

"Poor financial outcomes [for hospitals] could lead to poor care," said Naleef Fareed, assistant professor of health policy and administration, Penn State. "This is an issue that needs attention as health care reform moves forward."

Fareed and colleagues used data from both the American Hospital Association Annual Survey and the Centers for Medicare ...