(Press-News.org) Primary care physicians already have enough administrative duties on their plates, and the implementation of electronic medical records has only added to their burden. As a result, they have less time to spend with their patients.

But a new UCLA study suggests a simple way to lighten their load: a "physician partner" whose role would be to work on those administrative tasks, such as entering information into patient records, that take up so much of doctors' time. A physician partner allows doctors to focus more of their attention on their patients and leads to greater patient satisfaction with their care, the UCLA researchers say.

The study is published online in the peer-reviewed journal JAMA Internal Medicine.

"Patients want their doctors to spend time with them and give them the attention that makes them feel more confident in their medical care — they don't want to just sit there while their doctor is on the computer," said Dr. David Reuben, chief of the division of geriatrics at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and the study's primary investigator. "This also saves physicians a huge amount of time after patient sessions end, enabling them to spend more time with their families, keep up with the latest developments in medicine and come back refreshed the next day."

From November 2012 through June 2013, five physicians in two academic practices — three geriatricians and two general internists —each utilized physician partners over a total of 326 four-hour clinic sessions. The partners worked alongside the physicians during patient visits and participated in team huddles, transcribed physician comments into patients' records, pulled patient information from computer records, completed lab and referral requests, processed new prescriptions or medication refills, updated patient medication lists, scheduled follow-up appointments and provided patients with their visit summaries.

The physician partners were particularly beneficial for geriatricians, whose visits with patients averaged 2.8 minutes shorter with the partners than without them. Geriatricians also saved an average of 28.8 minutes over the four-hour sessions with the physician partners, compared with doctors who did not have a partner. By contrast, sessions for the doctors lacking a physician partner ran long by an average of 8.1 minutes.

The length of patient visits for the general internists who had a partner was not significantly shorter. These physicians did, however, spend less time between patients on visit preparation and note-writing, which allowed them to catch up on other work, such as returning calls and dealing with clinical issues involving patients who were not in the office. As a result, they saved nearly 40 minutes during the four-hour sessions and had essentially no paperwork remaining at the end of the sessions.

Among patients, 79 percent thought the physician partners contributed toward making their visit run smoothly, and only 18 percent were uncomfortable with the partners' presence. In addition, 88 percent of the patients whose doctors had a physician partner in the room strongly agreed that their physician spent enough time with them, compared with 75 percent whose physicians did not have a partner.

The study is limited by the fact that only five doctors in two practices at one academic health center participated in the study, and there were too few doctors to statistically analyze satisfaction and burnout scales, the researchers note. Also, the geriatric patients were more likely to feel comfortable with the physician partners in the room than the general medicine patients, perhaps because older patients are more accustomed to having someone else, such as a caregiver or family member, in the room during their doctor visits. Also, the researchers did not evaluate the quality of care the patients received.

Still, "the Physician Partners program provides a potential model to improve physician efficiency in the office setting without compromising patient satisfaction," the researchers write. "Implementation and dissemination will depend upon local factors including staff availability and training, adaptation to the patient population and practice characteristics, cost and reimbursement structures, and willingness to invest in change."

INFORMATION:

The UCLA Claude Pepper Older Americans Independence Center, funded by the National Institute on Aging (5P30AG028748), supported this project.

Study co-authors were Wendy Senelick, Eve Glazier and Brandon Koretz of UCLA, and Jennifer Knudsen of Harvard Medical School.

'Physician partners' free doctors to focus on patients, not paperwork

2014-05-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Negative stereotypes can cancel each other out on resumes

2014-05-15

Stereotypes of gay men as effeminate and weak and black men as threatening and aggressive can hurt members of those groups when white people evaluate them in employment, education, criminal justice and other contexts.

But the negative attributes of the two stereotypes can cancel one another out for gay black men in the employment context, according to research by a Princeton University graduate student in sociology, challenging the commonly held idea that membership in multiple marginalized groups leads to more discrimination than being a member of a single such group.

Sociologist ...

Penn Vet study reveals Salmonella's hideout strategy

2014-05-15

The body's innate immune system is a first line of defense, intent on sensing invading pathogens and wiping them out before they can cause harm. It should not be surprising then that bacteria have evolved many ways to specifically evade and overcome this sentry system in order to spread infection.

A study led by researchers in the University of Pennsylvania's School of Veterinary Medicine now reveals how some Salmonella bacteria hide from the immune system, allowing them to persist and cause systemic infection. The findings could help researchers craft a more effective ...

Research finds human impact may cause Sierra Nevada to rise, increase seismicity of San Andreas Fault

2014-05-15

RENO, Nev. – Like a detective story with twists and turns in the plot, scientists at the University of Nevada, Reno are unfolding a story about the rapid uplift of the famous 400-mile long Sierra Nevada mountain range of California and Nevada.

The newest chapter of the research is being published today in the scientific journal Nature, showing that draining of the aquifer for agricultural irrigation in California's Central Valley results in upward flexing of the earth's surface and the surrounding mountains due to the loss of mass within the valley. The groundwater subsidence ...

A skeleton clue to early American ancestry

2014-05-15

This news release is available in Spanish and Arabic.

The discovery of a near-complete human skeleton in a watery cave in Mexico is helping scientists answer the question, "Who were the first Americans?" The finding, reported in the 16 May issue of the journal Science, sheds new light on a decades-long debate among archaeologists and anthropologists.

Deciphering the ancestry of the first people to populate the Americas has been a challenge.

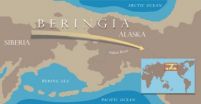

On the basis of genetics, modern Native Americans are thought to descend from Siberians who moved into eastern Beringia (the ...

Oldest most complete, genetically intact human skeleton in New World

2014-05-15

WASHINGTON (May 15, 2014)—The skeletal remains of a teenage female from the late Pleistocene or last ice age found in an underwater cave in Mexico have major implications for our understanding of the origins of the Western Hemisphere's first people and their relationship to contemporary Native Americans.

In a paper released today in the journal Science, an international team of researchers and cave divers present the results of an expedition that discovered a near-complete early American human skeleton with an intact cranium and preserved DNA. The remains were found surrounded ...

WSU anthropologist leads genetic study of prehistoric girl

2014-05-15

PULLMAN, Wash.—For more than a decade, Washington State University molecular anthropologist Brian Kemp has teased out the ancient DNA of goose and salmon bones from Alaska, human remains from North and South America, and human coprolites—ancient poop—from Oregon and the American Southwest.

His aim: use genetics as yet another archaeological record offering clues to the identities of ancient people and how they lived and moved across the landscape.

As head of the team studying the DNA of Naia, an adolescent girl who fell into a Yucatan sinkhole some 12,000 years ago, he ...

Genetic study helps resolve years of speculation about first people in the Americas

2014-05-15

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — A new study could help resolve a longstanding debate about the origins of the first people to inhabit the Americas, researchers report in the journal Science. The study relies on genetic information extracted from the tooth of an adolescent girl who fell into a sinkhole in the Yucatan 12,000 to 13,000 years ago.

The girl's remains were found alongside those of ancient extinct beasts that also fell into the "inescapable natural trap," as researchers described the sinkhole. The team used radiocarbon dating and analyzed chemical signatures in bones and ...

Dating and DNA show Paleoamerican-Native American connection

2014-05-15

Eastern Asia, Western Asia, Japan, Beringia and even Europe have all been suggested origination points for the earliest humans to enter the Americas because of apparent differences in cranial form between today's Native Americans and the earliest known Paleoamerican skeletons. Now an international team of researchers has identified a nearly complete Paleoamerican skeleton with Native American DNA that dates close to the time that people first entered the New World.

"Individuals from 9,000 or more years ago have morphological attributes -- physical form and structure -- ...

Genetic study confirms link between earliest Americans and modern Native-Americans

2014-05-15

AUSTIN, Texas — The ancient remains of a teenage girl found in an underwater Mexican cave establish a definitive link between the earliest Americans and modern Native Americans, according to a new study released today in the journal Science.

The study was conducted by an international team of researchers from 13 institutions, including Deborah Bolnick, assistant professor of anthropology at The University of Texas at Austin, who analyzed DNA from the remains simultaneously with independent researchers at Washington State University and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

The ...

First 'heavy mouse' leads to first lab-grown tissue mapped from atomic life

2014-05-15

Scientists have created a 'heavy' mouse, the world's first animal enriched with heavy but non-radioactive isotopes - enabling them to capture in unprecedented detail the molecular structure of natural tissue by reading the magnetism inherent in the isotopes.

This data has been used to grow biological tissue in the lab practically identical to native tissue, which can be manipulated and analysed in ways impossible for natural samples. Researchers say the approach has huge potential for scientific and medical breakthroughs: lab-grown tissue could be used to replace heart ...