(Press-News.org) (MEMPHIS, Tenn. – May 20, 2014) Researchers have demonstrated that an enzyme required for animal survival after birth functions like an umpire, making the tough calls required for a balanced response to signals that determine if cells live or die. St. Jude Children's Research Hospital scientists led the study, which was published online and appears in the May 22 edition of the scientific journal Cell.

The work involved the enzyme receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1). While RIPK1 is known to be involved in many vital cell processes, this study shows that its pivotal role in survival after birth is as an inhibitor of two different pathways that lead to the death of cells. Functioning properly, the pathways provide a way to get rid of dangerous, damaged or unneeded cells.

By removing different components of each pathway in different combinations, researchers demonstrated that after birth RIPK1 helps cells maintain a balanced response to signals that promote either pathway. "We are learning that in disease this balancing act can be perturbed to produce damage and cell death," said the study's corresponding author Douglas Green, Ph.D., chair of the St. Jude Department of Immunology.

The results resolve long-standing questions about RIPK1's role in cell survival and provide clues about how the disease-fighting immune system might use these pathways to contain infections. The findings have also prompted researchers to launch an investigation into whether RIPK1 could be harnessed to kill cancer cells or provide insight into tumor development. RIPK1 is already the focus of drug development efforts designed to limit cell damage following heart attack, stroke or kidney injury.

"This study fundamentally changes the way we think about RIPK1, a molecule that we care about because it is required for life," Green said. "The results helped us identify new pathways involved in regulating programmed cell death and suggest that we might be able to develop cancer therapies that target these the pathways or engage them in other ways to advance treatment of a range of diseases."

The study is one of two involving RIPK1 being published in the same edition of Cell.

The St. Jude report builds on previous research from Green's laboratory regarding regulation of the pathways that control two types of programmed cell death. One, called apoptosis, is driven by an enzyme named caspase-8. It forms a complex with a protein named FADD as well as other proteins that prompt cells to bundle themselves into neat packages for disposal. The other, called necroptosis, involves a different pathway that is orchestrated by the enzyme receptor-interacting protein kinase 3 (RIPK3). Researchers knew that before birth, RIPK1 worked through RIPK3 to trigger cell death by necroptosis, but until now the enzyme's primary role after birth was uncertain.

For this study, researchers bred mice lacking different combinations of genes for ripk1, ripk3, caspase-8, FADD and other components of both the apoptotic and necroptotic pathways.

Mice lacking ripk1 died. Mice missing two genes – ripk1 plus ripk3 or ripk1 plus caspase-8 or FADD – also died soon after birth. Mice survived and developed normally, however, when researchers removed three genes – ripk1, ripk3 and either caspase-8 or FADD. "The fact that the mice survived was totally unexpected and made us rethink how these pathways worked," Green said.

Added Christopher Dillon, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in Green's laboratory: "Knocking out two genes to restore balance following the loss of another gene, in this case RIPK1, is exceedingly rare." Dillon and St. Jude postdoctoral fellows Ricardo Weinlich, Ph.D., and Diego Rodriguez, Ph.D., are the paper's first authors.

The finding established RIPK1's premier role in cell survival as inhibition of apoptosis and necroptosis.

The results also demonstrated that other pathways must exist in cells to maintain a balanced response to signals pushing for cell death via apoptosis or necroptosis. Evidence in this study, for example, suggested one possible new pathway that triggered necroptosis using interferon and other elements of the immune response to infections.

INFORMATION:

The study's other authors are James Cripps, Giovanni Quarato, Prajwal Gurung, Katherine Verbist, Taylor Brewer, Fabien Llambi, Yi-Nan Gong, Laura Janke and Thirumala-Devi Kanneganti, all of St. Jude, and Michelle Kelliher, of the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, Mass.

The research was funded in part by grants (AI44828 and CA169291) from the National Institutes of Health and ALSAC.

St. Jude Media Relations Contacts

Carrie Strehlau

desk (901) 595-2295

cell (901) 297-9875

carrie.strehlau@stjude.org

Summer Freeman

desk (901) 595-3061

cell (901) 297-9861

summer.freeman@stjude.org

Molecule acts as umpire to make tough life-or-death calls

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital solves mystery of enzyme's role in cell survival, offering clues of how immune system fights infection and possible strategies to treat problems ranging from heart attack to cancer

2014-05-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Aggressive behavior observed after alcohol-related priming

2014-05-22

May 22, 2014-- Researchers from California State University, Long Beach, the University of Kent and the University of Missouri collaborated on a study to test whether briefly exposing participants to alcohol-related terms increases aggressive behavior. It has been well documented by previous research that the consumption of alcohol is directly linked to an increase in aggression and other behavioral extremes. But can simply seeing alcohol-related words have a similar effect on aggressive behavior?

Designing the experiment

The study, published in the journal Personality ...

First broadband wireless connection ... to the moon?!

2014-05-22

WASHINGTON, May 22, 2014—If future generations were to live and work on the moon or on a distant asteroid, they would probably want a broadband connection to communicate with home bases back on Earth. They may even want to watch their favorite Earth-based TV show. That may now be possible thanks to a team of researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's (MIT) Lincoln Laboratory who, working with NASA last fall, demonstrated for the first time that a data communication technology exists that can provide space dwellers with the connectivity we all enjoy here ...

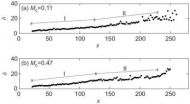

On quantification of the growth of compressible mixing layer

2014-05-22

CML has been a research topic for more than five decades, due to its wide applications in propulsion design. Mixing in CML is controlled by the compressibility effects of velocity and density variations over the mixing layer, and quantified by the growth rate of CML. However, the lack of understanding of various definitions of mixing thicknesses has yielded scatter in analyzing experimental data. Prof. SHE ZhenSu and his colleagues at the State Key Laboratory for Turbulence and Complex Systems, Peking University investigated the growth of compressible mixing layer by introducing ...

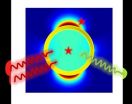

Nanoshell-emitters hybrid nanoobject was proposed as promising 2-photon fluorescence probe

2014-05-22

Two-photon excitation fluorescence is growing in popularity in the bioimaging field but is limited by fluorophores' extremely low two-photon absorption cross-section. The researcher Dr. Guowei Lu and co-workers from State Key Laboratory for Mesoscopic Physics, Department of Physics, Peking University, are endeavoring to develop efficient fluorescent probes with improved two-photon fluorescence (TPF) performance. They theoretically present a promising bright probe using gold nanoshell to improve the TPF performances of fluorescent emitters. Their work, entitled "Plasmonic-Enhanced ...

Stanford research shows importance of European farmers adapting to climate change

2014-05-22

A new Stanford study finds that due to an average 3.5 degrees Fahrenheit of warming expected by 2040, yields of wheat and barley across Europe will drop more than 20 percent.

New Stanford research reveals that farmers in Europe will see crop yields affected as global temperatures rise, but that adaptation can help slow the decline for some crops.

For corn, the anticipated loss is roughly 10 percent, the research shows. Farmers of these crops have already seen yield growth slow down since 1980 as temperatures have risen, though other policy and economic factors have ...

Symbiosis or capitalism? A new view of forest fungi

2014-05-22

The so-called symbiotic relationship between trees and the fungus that grow on their roots may actually work more like a capitalist market relationship between buyers and sellers, according to the new study published in the journal New Phytologist.

Recent experiments in the forests of Sweden had brought into a question a long-held theory of biology: that the fungi or mycorrhizae that grow on tree roots work with trees in a symbiotic relationship that is beneficial for both the fungi and the trees, providing needed nutrients to both parties. These fungi, including many ...

Stanford, MIT scientists find new way to harness waste heat

2014-05-22

Vast amounts of excess heat are generated by industrial processes and by electric power plants. Researchers around the world have spent decades seeking ways to harness some of this wasted energy. Most such efforts have focused on thermoelectric devices – solid-state materials that can produce electricity from a temperature gradient – but the efficiency of such devices is limited by the availability of materials.

Now researchers at Stanford University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have found a new alternative for low-temperature waste-heat conversion into ...

A new target for alcoholism treatment: Kappa opioid receptors

2014-05-22

Philadelphia, PA, May 22, 2014 – The list of brain receptor targets for opiates reads like a fraternity: Mu Delta Kappa. The mu opioid receptor is the primary target for morphine and endogenous opioids like endorphin, whereas the delta opioid receptor shows the highest affinity for endogenous enkephalins. The kappa opioid receptor (KOR) is very interesting, but the least understood of the opiate receptor family.

Until now, the mu opioid receptor received the most attention in alcoholism research. Naltrexone, a drug approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for ...

Higher discharge rate for BPD in children and adolescents in the US compared to UK

2014-05-22

Washington D.C., May 22, 2014 – A study published in the June 2014 issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry found a very much higher discharge rate for pediatric bipolar (PBD) in children and adolescents aged 1-19 years in the US compared to England between the years 2000-2010.

Using the English NHS Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) dataset and the US National Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS) to compare US and English discharge rates for PBD over the period 2000-2010, the authors found a 72.1-fold higher discharge rate for pediatric ...

Liquid crystal as lubricant

2014-05-22

Lubricants are used in motors, axels, ventilators and manufacturing machines. Although lubricants are widely used, there have been almost no fundamental innovations for this product in the last twenty years. Together with a consortium, the Fraunhofer Institute for Mechanics of Materials IWM in Freiburg has developed an entirely new class of substance that could change everything: liquid crystalline lubricant. Its chemical makeup sets it apart; although it is a liquid, the molecules display directional properties like crystals do. When two surfaces move in opposite directions, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists reveal our best- and worst-case scenarios for a warming Antarctica

Cleaner fish show intelligence typical of mammals

AABNet and partners launch landmark guide on the conservation of African livestock genetic resources and sustainable breeding strategies

Produce hydrogen and oxygen simultaneously from a single atom! Achieve carbon neutrality with an 'All-in-one' single-atom water electrolysis catalyst

Sleep loss linked to higher atrial fibrillation risk in working-age adults

Visible light-driven deracemization of α-aryl ketones synergistically catalyzed by thiophenols and chiral phosphoric acid

Most AI bots lack basic safety disclosures, study finds

How competitive gaming on discord fosters social connections

CU Anschutz School of Medicine receives best ranking in NIH funding in 20 years

Mayo Clinic opens patient information office in Cayman Islands

Phonon lasers unlock ultrabroadband acoustic frequency combs

Babies with an increased likelihood of autism may struggle to settle into deep, restorative sleep, according to a new study from the University of East Anglia.

National Reactor Innovation Center opens Molten Salt Thermophysical Examination Capability at INL

International Progressive MS Alliance awards €6.9 million to three studies researching therapies to address common symptoms of progressive MS

Can your soil’s color predict its health?

Biochar nanomaterials could transform medicine, energy, and climate solutions

Turning waste into power: scientists convert discarded phone batteries and industrial lignin into high-performance sodium battery materials

PhD student maps mysterious upper atmosphere of Uranus for the first time

Idaho National Laboratory to accelerate nuclear energy deployment with NVIDIA AI through the Genesis Mission

Blood test could help guide treatment decisions in germ cell tumors

New ‘scimitar-crested’ Spinosaurus species discovered in the central Sahara

“Cyborg” pancreatic organoids can monitor the maturation of islet cells

Technique to extract concepts from AI models can help steer and monitor model outputs

Study clarifies the cancer genome in domestic cats

Crested Spinosaurus fossil was aquatic, but lived 1,000 kilometers from the Tethys Sea

MULTI-evolve: Rapid evolution of complex multi-mutant proteins

A new method to steer AI output uncovers vulnerabilities and potential improvements

Why some objects in space look like snowmen

Flickering glacial climate may have shaped early human evolution

First AHA/ACC acute pulmonary embolism guideline: prompt diagnosis and treatment are key

[Press-News.org] Molecule acts as umpire to make tough life-or-death callsSt. Jude Children's Research Hospital solves mystery of enzyme's role in cell survival, offering clues of how immune system fights infection and possible strategies to treat problems ranging from heart attack to cancer