(Press-News.org) May 22, 2014, New York, NY – A Ludwig Cancer Research study has identified a novel pathway by which proteins are actively and specifically shuttled into the nucleus of a cell. Published online today in Cell, the finding captures a precise molecular barcode that flags proteins for such import and describes the biochemical interaction that drives this critically important process. The discovery could help illuminate the molecular dysfunction that underpins a broad array of ailments, ranging from autoimmune diseases to cancers.

Although small proteins can diffuse passively through pores built into the nuclear membrane, most nuclear proteins have to be actively driven into the nucleus through specialized pores to ensure that the cell functions normally. Proteins targeted to specific compartments in cells often carry a sequence of amino acids that, like a barcode, tells components of the cell's transport machinery where they should be located in order to perform their biochemical duties.

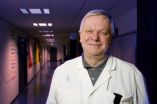

"Until now, only one nuclear import pathway for active transport has been extensively characterized," says Xin Lu, Ludwig director at the University of Oxford whose laboratory led the study. "It targets proteins that encode what's known as the nuclear localization signal (NLS). Yet about half of the proteins that get into the nucleus do not bear an NLS, and how they get there has long puzzled researchers. Now we have discovered an alternative signal by which proteins devoid of NLS are tagged for nuclear import." The finding will help scientists better understand the roles many hitherto poorly characterized proteins play in cellular life, and identify many others that work within the nucleus on such tasks as gene regulation and expression.

The researchers were led to their discovery while investigating how an important tumor suppressor protein known as ASPP, which Lu's laboratory has been studying for many years, gets into the nucleus. Their experiments revealed that a widely shared element of protein structure found in ASPP, known as the ankyrin repeat (AR), plays a central role in the protein's nuclear localization.

Lu's team shows in the study that the import signal that flags proteins for the new pathway consists of two consecutive ARs that share one feature: each has a hydrophobic amino acid (one with chemical properties that repel water) that is located 13 amino acids into the repeat. This structural signature, they find, is bound by a small protein named RanGDP. Lu and her colleagues have named this new pathway the RaDAR (RanGDP-Ankyrin Repeat) nuclear import pathway. They have so far identified more than 46 proteins encoded by the human genome that carry this barcode for nuclear delivery.

In decoding this new nuclear import signal, Lu and her team also uncover a possible molecular mechanism underlying human familial melanomas, which are often linked to mutations in a protein known as p16. "We show that the p16 mutation most frequently associated with such cancers," Lu explains, "confers the RaDAR barcode to the protein, resulting in its aberrant accumulation in the nucleus." The RaDAR signature is also associated with a number of regulators of cell proliferation and gene regulation, including the NF-kB family of proteins, which shuttle between the cytoplasm and nucleus, and have been implicated in several human cancers, and autoimmune and inflammatory diseases.

Lu's team is now investigating the spectrum of proteins that use the RaDAR pathway and exploring methods by which the ankyrin repeat that bears that barcode might be exploited to develop entirely novel diagnostics and therapies. That includes incorporating the new nuclear import barcode into synthetic molecules named DARPins to target biologics and other kinds of drugs specifically to the nucleus.

INFORMATION:

Funding for this research was provided by the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research.

About Ludwig Cancer Research

Ludwig Cancer Research is an international collaborative network of acclaimed scientists with a 40-year legacy of pioneering cancer discoveries. Ludwig combines basic research with the ability to translate its discoveries and conduct clinical trials to accelerate the development of new cancer diagnostics and therapies. Since 1971, Ludwig has invested more than $2.5 billion in life-changing cancer research through the not-for-profit Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research and the six U.S.-based Ludwig Centers.

Xin Lu is Director of the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research Oxford and a Professor of Cancer Biology at the University of Oxford's Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine.

For further information please contact Rachel Steinhardt, rsteinhardt@licr.org or +1-212-450-1582.

RaDAR guides proteins into the nucleus

Ludwig researchers discover a new pathway by which proteins are shuttled into the nucleus, and a hint of its role in a kind of melanoma

2014-05-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Wondering about the state of the environment? Just eavesdrop on the bees

2014-05-22

VIDEO:

This shows bees on dandelions.

Click here for more information.

Researchers have devised a simple way to monitor wide swaths of the landscape without breaking a sweat: by listening in on the "conversations" honeybees have with each other. The scientists' analyses of honeybee waggle dances reported in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on May 22 suggest that costly measures to set aside agricultural lands and let the wildflowers grow can be very beneficial to bees.

"In ...

Blocking pain receptors found to extend lifespan in mammals

2014-05-22

Chronic pain in humans is associated with worse health and a shorter lifespan, but the molecular mechanisms underlying these clinical observations have not been clear. A study published by Cell Press May 22nd in the journal Cell reveals that the activity of a pain receptor called TRPV1 regulates lifespan and metabolic health in mice. The study suggests that pain perception can affect the aging process and reveals novel strategies that could improve metabolic health and longevity in humans.

"The TRPV1 receptor is a major drug target with many known drugs in the clinic ...

Genes discovered linking circadian clock with eating schedule

2014-05-22

LA JOLLA—For most people, the urge to eat a meal or snack comes at a few, predictable times during the waking part of the day. But for those with a rare syndrome, hunger comes at unwanted hours, interrupts sleep and causes overeating.

Now, Salk scientists have discovered a pair of genes that normally keeps eating schedules in sync with daily sleep rhythms, and, when mutated, may play a role in so-called night eating syndrome. In mice with mutations in one of the genes, eating patterns are shifted, leading to unusual mealtimes and weight gain. The results were published ...

New technology may help identify safe alternatives to BPA

2014-05-22

Numerous studies have linked exposure to bisphenol A (BPA) in plastic, receipt paper, toys, and other products with various health problems from poor growth to cancer, and the FDA has been supporting efforts to find and use alternatives. But are these alternatives safer? Researchers reporting in the Cell Press journal Chemistry & Biology have developed new tests that can classify such compounds' activity with great detail and speed. The advance could offer a fast and cost-effective way to identify safe replacements for BPA.

Millions of tons of BPA and related compounds ...

Discovery of how Taxol works could lead to better anticancer drugs

2014-05-22

VIDEO:

This video shows how the constant addition of tubulin bound to GTP provides a cap that prevents the microtubule from falling apart. UC Berkeley scientists found that the hydrolyzation of...

Click here for more information.

University of California, Berkeley, scientists have discovered the extremely subtle effect that the prescription drug Taxol has inside cells that makes it one of the most widely used anticancer agents in the world.

The details, involving the drug's ...

Gene behind unhealthy adipose tissue identified

2014-05-22

Researchers at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden have for the first time identified a gene driving the development of pernicious adipose tissue in humans. The findings imply, which are published in the scientific journal Cell Metabolism, that the gene may constitute a risk factor promoting the development of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes.

Adipose tissue can expand in two ways: by increasing the size and/or the number of the fat cells. It is well established that subjects with few but large fat cells, so-called hypertrophy, display an increased risk of developing ...

Computer models helping unravel the science of life?

2014-05-22

Scientists have developed a sophisticated computer modelling simulation to explore how cells of the fruit fly react to changes in the environment.

The research, published today in the science journal Cell, is part of an on-going study at The Universities of Manchester and Sheffield that is investigating how external environmental factors impact on health and disease.

The model shows how cells of the fruit fly communicate with each other during its development. Dr Martin Baron, who led the research, said: "The work is a really nice example of researchers from different ...

Supportive tissue in tumors hinders, rather than helps, pancreatic cancer

2014-05-22

HOUSTON – Fibrous tissue long suspected of making pancreatic cancer worse actually supports an immune attack that slows tumor progression but cannot overcome it, scientists at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center report in the journal Cancer Cell.

"This supportive tissue that's abundant in pancreatic cancer tumors is not a traitor as we thought but rather an ally that is fighting to the end. It's a losing battle with cancer cells, but progression is much faster without their constant resistance," said study senior author Raghu Kalluri, Ph.D., M.D., chair ...

Blocking pain receptors extends lifespan, boosts metabolism in mice

2014-05-22

Blocking a pain receptor in mice not only extends their lifespan, it also gives them a more youthful metabolism, including an improved insulin response that allows them to deal better with high blood sugar.

"We think that blocking this pain receptor and pathway could be very, very useful not only for relieving pain, but for improving lifespan and metabolic health, and in particular for treating diabetes and obesity in humans," said Andrew Dillin, a professor of molecular and cell biology at the University of California, Berkeley, and senior author of a new paper describing ...

One molecule to block both pain and itch

2014-05-22

Duke University researchers have found an antibody that simultaneously blocks the sensations of pain and itching in studies with mice.

The new antibody works by targeting the voltage-sensitive sodium channels in the cell membrane of neurons. The results appear online on May 22 in Cell.

Voltage-sensitive sodium channels control the flow of sodium ions through the neuron's membrane. These channels open and close by responding to the electric current or action potential of the cells. One particular type of sodium channel, called the Nav1.7 subtype, is responsible for ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Roadmap for Europe’s biodiversity monitoring system

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

[Press-News.org] RaDAR guides proteins into the nucleusLudwig researchers discover a new pathway by which proteins are shuttled into the nucleus, and a hint of its role in a kind of melanoma