(Press-News.org) BOZEMAN, Mont. – Scientists have discovered that the rapid spread of hybridization between a native species and an invasive species of trout in the wild is strongly linked to changes in climate.

In the study, stream temperature warming over the past several decades and decreases in spring flow over the same time period contributed to the spread of hybridization between native westslope cutthroat trout and introduced rainbow trout – the world's most widely introduced invasive fish species –across the Flathead River system in Montana and British Columbia, Canada.

Experts have long predicted that climate change could decrease worldwide biodiversity through cross-breeding between invasive and native species, but this study is the first to directly and scientifically support this assumption. The study, published today in Nature Climate Change, was based on 30 years of research by scientists with the U.S. Geological Survey, University of Montana, and Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks.

Hybridization has contributed to the decline and extinction of many native fishes worldwide, including all subspecies of cutthroat trout in western North America, which have enormous ecological and socioeconomic value. The researchers used long-term genetic monitoring data coupled with high-resolution climate and stream temperature predictions to assess whether climate warming enhances interactions between native and nonnative species through hybridization.

"Climatic changes are threatening highly prized native trout as introduced rainbow trout continue to expand their range and hybridize with native populations through climate-induced 'windows of opportunity,' putting many populations and species at greater risk than previously thought," said project leader and USGS scientist Clint Muhlfeld. "The study illustrates that protecting genetic integrity and diversity of native species will be incredibly challenging when species are threatened with climate-induced invasive hybridization."

Westslope cutthroat trout and rainbow trout both spawn in the spring and can produce fertile offspring when they interbreed. Over time, a mating population of native and non-native fish will result in only hybrid individuals with substantially reduced fitness because their genomes have been infiltrated by nonnative genes that are maladapted to the local environment. Thus, protecting and maintaining the genetic integrity of native species is important for a species' ability to be resilient and better adapt to a rapidly changing climate.

Historical genetic samples revealed that hybridization between the two fish species was largely confined to one downstream Flathead River population. However, the study noted, over the past 30 years, hybridization rapidly spread upstream, irreversibly reducing the genetic integrity of native westslope cutthroat trout populations. Genetically pure populations of westslope cutthroat trout are known to occupy less than 10 percent of their historical range.

The rapid increase in hybridization was highly associated with climatic changes in the region. From 1978 to 2008 the rate of warming nearly tripled in the Flathead basin, resulting in earlier spring runoff, lower spring flooding and flows, and warming summer stream temperatures. Those locations with the greatest changes in stream flow and temperature experienced the greatest increases in hybridization.

Relative to cutthroat trout, rainbow trout prefer these climate-induced changes, and tolerate greater environmental disturbance. These conditions have likely enhanced rainbow trout spawning and population numbers, leading to massive expansion of hybridization with westslope cutthroat trout.

"The evolutionary consequences of climate change are one of our greatest areas of uncertainty because empirical data addressing this issue are extraordinarily rare; this study is a tremendous step forward in our understanding of how climate change can influence evolutionary process and ultimately species biodiversity," said Ryan Kovach, a University of Montana study co-author.

Overall, aquatic ecosystems in western North America are predicted to experience increasingly earlier snowmelt in the spring, reduced late spring and summer flows, warmer and drier summers, and increased water temperatures – all of which spell increased hybridization between these species.

INFORMATION:

The article, published in Nature Climate Change, is titled "Invasive hybridization in a threatened species is accelerated by climate change" and can be viewed at the following website. Its authors are Clint Muhlfeld, U.S. Geological Survey; Ryan Kovach, University of Montana; Leslie Jones, U.S. Geological Survey; Robert Al-Chokhachy, U.S. Geological Survey; Matthew Boyer, Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks; Robb Leary, Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks; Winsor Lowe, University of Montana; Gordon Luikart, University of Montana; and Fred Allendorf, University of Montana.

This study was supported by the Great Northern Landscape Conservation Cooperative, the Interior Department's Northwest Climate Science Center, the National Climate Change and Wildlife Science Center, National Science Foundation, and Bonneville Power Administration.

More information about impacts and prevention of invasive species and hybridization can be found on the USGS Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center website.

Photos available at http://gallery.usgs.gov/photo_shares/thumbs/tags/NR2014_05_25/1

USGS provides science for a changing world. Visit USGS.gov, and follow us on Twitter @USGS and our other social media channels.

Climate change accelerates hybridization between native and invasive species of trout

2014-05-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New perspectives to the design of molecular cages

2014-05-27

Researchers from the University of Jyväskylä report a new method of building molecular cages. The method involves the exploitation of intermolecular steric effects to control the outcome of a self-assembly reaction.

Molecular cages are composed of organic molecules (ligands) which are bound to metal ions during a self-assembly process. Depending on the prevailing conditions, self-assembly processes urge to maximize the symmetry of the system and thus occupy every required metal binding site. The research group led by docent Manu Lahtinen (University of Jyväskylä, Department ...

Molecules do the triple twist

2014-05-27

An international research team led by Academy Professor Kari Rissanen of the University of Jyväskylä (Finland) and Professor Rainer Herges of the University of Kiel (Germany) has managed to make a triple-Möbius annulene, the most twisted fully conjugated molecule to date, as reported in Nature Chemistry (DOI:10.1038/nchem.1955, published online 25 May 2014).

An everyday analogue of a single twisted Möbius molecule is a Möbius strip. It can be made easily by twisting one end of a paper strip by 180 degrees and then joining the two ends. A triple twisted Möbius molecule ...

Insights into genetics of cleft lip

2014-05-27

Scientists at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Heidelberg, have identified how a specific stretch of DNA controls far-off genes to influence the formation of the face. The study, published today in Nature Genetics, helps understand the genetic causes of cleft lip and cleft palate, which are among the most common congenital malformations in humans.

"This genomic region ultimately controls genes which determine how to build a face and genes which produce the basic materials needed to execute this plan", says François Spitz from EMBL, who led the work. ...

Clinical trial reaffirms diet beverages play positive role in weight loss

2014-05-27

May 27, 2014 – A groundbreaking new study published today in Obesity, the journal of The Obesity Society, confirms definitively that drinking diet beverages helps people lose weight.

"This study clearly demonstrates that diet beverages can in fact help people lose weight, directly countering myths in recent years that suggest the opposite effect – weight gain," said James O. Hill, Ph.D., executive director of the University of Colorado Anschutz Health and Wellness Center and a co-author of the study. "In fact, those who drank diet beverages lost more weight and reported ...

Heavily decorated classrooms disrupt attention and learning in young children

2014-05-27

VIDEO:

Maps, number lines, shapes, artwork and other materials tend to cover elementary classroom walls. However, new research from Carnegie Mellon University shows that too much of a good thing may...

Click here for more information.

PITTSBURGH—Maps, number lines, shapes, artwork and other materials tend to cover elementary classroom walls. However, new research from Carnegie Mellon University shows that too much of a good thing may end up disrupting attention and learning in ...

Migrating stem cells possible new focus for stroke treatment

2014-05-27

Two years ago, a new type of stem cell was discovered in the brain that has the capacity to form new cells. The same research group at Lund University in Sweden has now revealed that these stem cells, which are located in the outer blood vessel wall, appear to be involved in the brain reaction following a stroke.

The findings show that the cells, known as pericytes, drop out from the blood vessel, proliferate and migrate to the damaged brain area where they are converted into microglia cells, the brain's inflammatory cells.

Pericytes are known to contribute to tissue ...

Health issues, relationship changes trigger economic spirals for low-income rural families

2014-05-27

When it comes to the factors that can send low-income rural families into a downward spiral, health issues and relationship changes appear to be major trigger events. Fortunately, support networks – in particular, extended families – can help ease these poverty spells, according to new research from the NH Agricultural Experiment Station at the University of New Hampshire College of Life Sciences and Agriculture.

The research was conducted by Elizabeth Dolan, emeritus associate professor of family studies at UNH, and her colleagues Sheila Mammen at the University of ...

Africa's longest-known terrestrial wildlife migration discovered

2014-05-27

WASHINGTON, DC - Researchers have documented the longest-known terrestrial migration of wildlife in Africa – up to several thousand zebra covering a distance of 500km (more than 300 miles) – according to World Wildlife Fund (WWF).

Using GPS collars on eight adult Plains zebra (Equus quagga), WWF and Namibia's Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET), in collaboration with Elephants Without Borders (EWB) and Botswana's Department of Wildlife and National Parks, tracked two consecutive years of movement back and forth between the Chobe River in Namibia and Botswana's Nxai ...

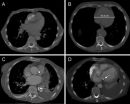

Chest CT helps predict cardiovascular disease risk

2014-05-27

OAK BROOK, Ill. – Incidental chest computed tomography (CT) findings can help identify individuals at risk for future heart attacks and other cardiovascular events, according to a new study published online in the journal Radiology.

"In addition to diagnostic purposes, chest CT can be used for the prediction of cardiovascular disease," said Pushpa M. Jairam, M.D., Ph.D., from the University Medical Center Utrecht, in Utrecht, the Netherlands. "With this study, we have taken a new perspective by providing a different approach for cardiovascular disease risk prediction ...

An area's level of poverty or wealth may affect the distribution of cancer types

2014-05-27

A new analysis has found that certain cancers are more concentrated in areas with high poverty, while other cancers arise more often in wealthy regions. Also, areas with higher poverty had lower cancer incidence and higher mortality than areas with lower poverty. Published early online in CANCER, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society, the study's findings demonstrate the importance of including measures of socioeconomic status in national cancer surveillance efforts.

Overall, socioeconomic status is not related to cancer risk—cancer strikes the rich and ...